Warning: This article contains images of dead animals.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand is probably best remembered not for his life, but for the manner of his death. Were it not for the fact that he took a detour through the streets of Sarajevo and ran into Gavrilo Princip, the archduke might have lived a life devoid of incident. Instead, the spilling of his noble blood led to World War I and the death of millions. Yet, long before that fateful summer day, Franz Ferdinand had shed a lot of blood himself, not in the name of politics or conflict, but entertainment. Archduke Franz Ferdinand didn’t just like hunting – he loved it, and the man who died by the bullet lived by it too.

In his lifetime, Franz Ferdinand’s trigger finger took down 274,899 animals, a number confirmed by his meticulously kept records. He lived in palaces and hunting lodges that were stuffed with the grim trophies of his kills, all sorts of exotic remains lining every wall of every room to bear testament to his hunting prowess. In fact, Ferdinand bagged so many beasts on his world tour that he dreamed of opening a museum to show them off.

To bring the scale of his killings into perspective, in a hunting career spanning over half a decade, the keen and dedicated hunter Emperor Franz Joseph killed 48,000 animals. Of course, unlike the emperor, the enthusiastic archduke embraced technology, sometimes even mowing down his prey with a machine gun.

When he set off on an educational trip around the world in December 1892, Ferdinand was armed and ready with weapons to kill and a journal in which to record every animal slain. The plan was for the emperor-to-be to engage in some diplomatic glad-handing, but when he disappeared into the sunset aboard the Kaiserin Elisabeth, Ferdinand was thinking of the hunts ahead.

Ferdinand’s trip took him to destinations including Ceylon, India, Nepal, North America and Australia. His journal charts not just the diplomatic highs and lows of his travels, but also the rowdy celebrations of those on board the Elisabeth. They also chart each hunt in sometimes distressing detail, leaving a lasting testament to Ferdinand’s dedication to his hobby.

The archduke left Vienna in December 1892 and two days later he was sailing out of Trieste aboard the pride of the navy. Just a few days shy of his 19th birthday, Ferdinand was accompanied to the boat by his family, but they weren’t part of the tour party. Although his journal betrays a few pangs of anxiety about what was to come, the young man was determined to enjoy whatever the voyage threw at him. He was hungry for adventure.

The first entry in the journal reflects a traveller finding his feet, gazing in wonder at the stunning vistas, making weather reports and diligently listing naval exercises; it’s a whole two days before the parties begin. Things started with a small celebration on the eve of Ferdinand’s birthday, complete with three cheers, fireworks and music. It was all rather respectable and innocent, yet on the big day itself, things got a bit more elaborate.

On the archduke’s birthday, the sailors held a procession of wild animals for his entertainment. Of course, there’s a distinct shortage of mammals in the middle of the ocean and instead, crewmen constructed elaborate costumes better suited to pantomime to perform as elephants, crocodiles and more. Ferdinand reported gleefully of sailors dressed as “jet black zulu kaffirs” who danced lustily for his entertainment and he lapped it up. Not only was such silliness great fun, he reflected, but it showed too how crewmen from all over Europe came together in the spirit of fun. These pantomime elephants and sailors in blackface left him not only rolling with laughter, but bristling with national and naval pride. It’s possible these panto animals left Ferdinand’s trigger finger itching too but sailors were, of course, off limits for hunting.

The social life on board appealed to Ferdinand, who enjoyed settling for a drink beneath the stars to sing shanties and tell tales. He described dressing a Christmas tree at sea, yodelling and partying in the middle of the empty ocean beneath a blazing sun while his countrymen did the same beneath a frozen sky at home. Short stopovers were made, ceremonies and diplomatic business performed and all manner of sea creatures spotted as the days passed. Reading his journals, one can’t deny Ferdinand was finding much to enjoy on this so-far bloodless adventure. It wouldn’t stay bloodless for long.

Soon Franz Ferdinand was shooting rays from the bridge of the ship, hungry for the kill, and when the party arrived in Ceylon, the hunting began in earnest. The visitors were received in fine style in Kandy and treated to a display of local traditions and a tour, which left the archduke revelling in his new surroundings. That youthful excitement was truly breathless when he set off for his first hunting trip of the tour and the journals crackle with anticipation, laying bare the sheer passion he felt for his hobby. Businesslike reports on the planning of the tour give way to an excitable narrative detailing an elephant hunt, the culmination of a long-held ambition.

In fact, though Ferdinand managed to wound an elephant (it was sick, he assures us), he didn’t succeed in killing any. Given the evocative and touching description of a mother elephant grazing with her sleeping calf at her feet, this comes as a relief to the reader. Ferdinand’s writing, however, seethes with his annoyance at his failed efforts. He contents himself with taking potshots at birds, while another member of the party gathers monkeys and yet more avian prey.

The following day, Ferdinand was excited to hear that the wounded elephant had been spotted. Once again the party pursued the creature but again it escaped. With the men bristling with disappointment, the archduke turned his weapon on an enormous lizard and he shared his joy at the cracking of its skull. Despite this, our hunters felt little pleasure in their uninspiring kills that day and drank their cares away deep into the night, lamenting the hunter’s curse that had befallen them.

Ferdinand fixated on killing an elephant, any elephant, raging at his companions when their shots frightened away the herd the next day. Finally though, just as he had given up hope, he killed not one but two of the great creatures. Terrified by being hunted for 48 hours, the herd retreated to what seemed like safety; instead, they became easy pickings. Later that day he celebrated by gleefully shooting monkeys, birds and when the Sun went down and the drink flowed, the party was on…

As the tour rolled into India, Ferdinand undertook a trip to a hospital for sick animals. His journals betray his utter befuddlement and distaste at the institution he describes as an aberration. Ever the pragmatist, he found no earthly reason for such a place to exist other than misguided religious sentimentality. He was not entirely without sympathy though, reacting with horror when he saw local people mistreating the oxen that drew wagons – these were working beasts, after all, deserving of proper treatment.

India was to prove rich hunting ground, and as he crossed the subcontinent, shots rang out. Delighted to hear the injured elephant from Ceylon had been found dead, he celebrated by poaching birds from a moving train, which he laughingly reported as accidental. The list of prey in India continued to come thick and fast.

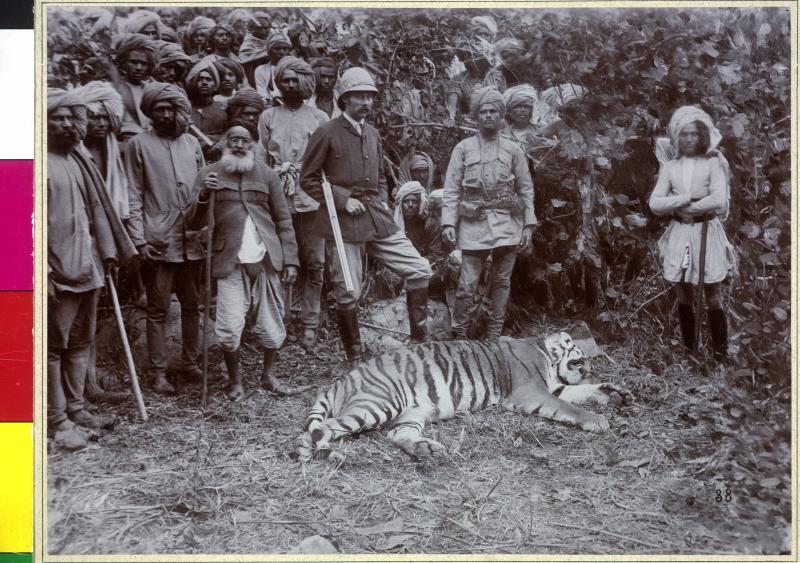

For days they tracked a tiger without success and Ferdinand’s frustration is clear in every written word. Unsuccessful hunting trips were rarely the fault of the archduke nor his Western party but, “The dullness and unreliability of the natives,” though he found local hospitality refreshing. He catalogued near-naked wrestling, magnificent temples and fine dinners; cakes filled with live birds and the finest culture the country could offer. Frustrated by his inability to hunt a tiger he was, nevertheless, given two as gifts to take home, reporting that they were no different to domestic cats.

As the days passed, the tiger remained elusive, thick fog blighting the hunt, but the archduke was determined. When he finally killed the tiger he sought and fatally wounded a second that his comrade finished off, he was overcome with joy. He waxed lyrical about, “The most beautiful hunting memory of my life,” offering “Warm thanks to Saint Hubertus for such a successful hunt.” No doubt the tigers felt considerably less blessed.

From Ferdinand’s journals, distinct personalities begin to emerge. We meet the unnamed crewmen from across Europe who revel in simple pleasures, the companions who seem given to illness or attempt to match him during a hunt, and the bastions of empire who host glittering social events. There are young princes and old tiger keepers, hunting guides and local shopkeepers, all of who fill in the rich tapestry of his travels. He revels in museums and botanical and natural collections, and along the voyage, begins to assemble quite a collection of living animals that will accompany him home. In Darjeeling, his green credentials rather come to the fore as, distressed to see the jungle burning to make room to grow tea, Ferdinand comments darkly that the wood will revenge itself on man.

In fact, it is these portions of the journal that prove far more illuminating than the procession of hunting tales, lending a unique look at a culture experienced through a very particular pair of eyes. Ferdinand was not a man who readily trusted those of other nationalities, and experiencing these far-off lands in his own words makes for an absorbing experience. He shares his thoughts on how royal heirs are raised across the world, reflecting on religious and social differences, albeit with more than the occasional bit of utter astonishment.

When Ferdinand and his party hit Nepal, hunting tigers was the only thing on their minds. The pickings were rich as big cats, elephants, eagles and other trophies died at their hands. Australia provided a smorgasbord of prey and Ferdinand made sport of the continent’s most iconic creatures. He killed emus, kangaroos and in a particularly distressing episode, a koala and its babe. Celebrations were great, the archduke was in his element and all seemed right with the hunting world as he lapped up the adulation of his Australian guides.

The rifle, as Ferdinand put it so poetically, had to rest in Japan as both schedule and season were wrong for game hunting. Instead he enjoyed a cultural interlude, touring cities, meeting dignitaries and killing precisely nothing. Whether entertaining the locals by showing off their Western physiques in kimonos or shopping for souvenirs, it is in the Japanese pages of the journal that the tourist in Ferdinand can be glimpsed. He got an enormous tattoo, “Which I will probably come to regret,” went sightseeing and fired off a few photos. Not quite a lads’ holiday as we know it now, but certainly containing a few of the required elements.

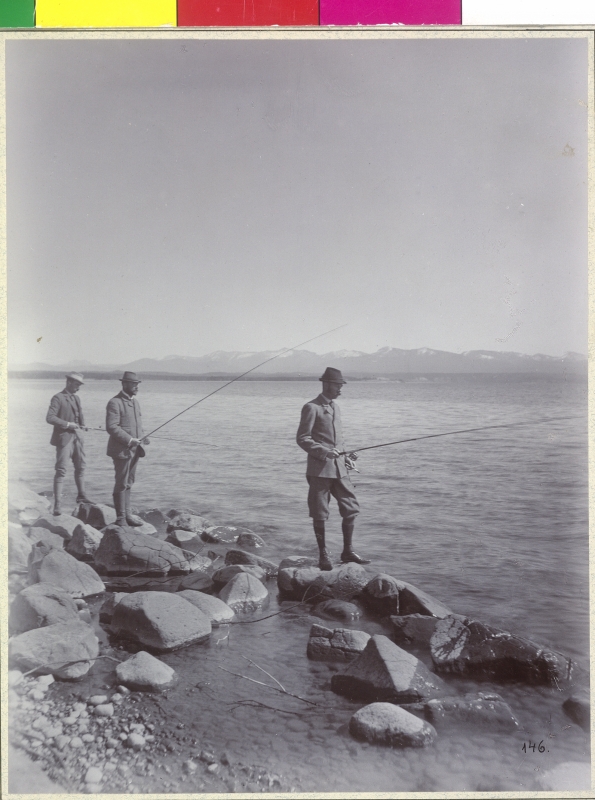

From there it was more environmental angst in Canada and, of course, grizzly bear hunting. Particularly saddening is the archduke’s excitement on discovering the trail of a “happy mother and its cub,” leaving the reader certain they will not be happy for long. In fact, the bears escaped Ferdinand’s sights and, struck down by a cold, the great hunter had no choice but to admit defeat.

On arrival in Yellowstone Park, Ferdinand was delighted to note the richness of game but this was somewhat lessened by the fact he couldn’t shoot any of it due to a total ban on hunting. The reader can feel his frustration as he sees creatures that he longs to take a shot at and simply can’t. Upon meeting some German hunters on their way to a shoot, he discovered that their rifle barrels had been sealed by rangers, just in case.

Ferdinand would not be stopped though and, determined to bag one kill in the park, he and his companions beat a skunk to death. They attacked porcupines and squirrels too, the whole experience written up with gleeful amusement. Ferdinand was delighted to have got one over on authorities, sure that he couldn’t be forbidden from hunting anywhere.

The long journey home to Europe began in October 1893. With Ferdinand’s hunting world tour finally at an end, he set off on the long voyage home, the ship’s hold stuffed with trophies both living and dead.

For more on the House of Habsburg, subscribe to subscribe to History of Royals and get every issue delivered straight to your drawbridge.

Sources:

- G Brook-Shepherd, Royal Sunset: Dynasties Of Europe And The Great War Hardcover, Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1987

- G Brook-Shepherd, Victims At Sarajevo: The Romance And Tragedy Of Franz Ferdinand And Sophie, HarperCollins 1984

- G King and S Woolmans, The Assassination Of The Archduke: Sarajevo 1914 And The Murder That Changed the World, Macmillan 2013

- RN Lebow, Archduke Franz Ferdinand Lives!: A World Without World War I, St Martin’s Press 2014