A single cart drawn by two huge white horses travels through the streets of Paris as a ravenous crowd fights to catch a glimpse of the woman within. Her hands are bound but her back is straight and her expression is hard and proud. Her famous blonde hair has turned a premature grey, and the figure that was once dainty and slender has grown large with rich palace meals. She sits frozen in place while the crowd spit and yell insults at her. Her name is Marie Antoinette, formerly the queen of France, and the people are screaming for her blood.

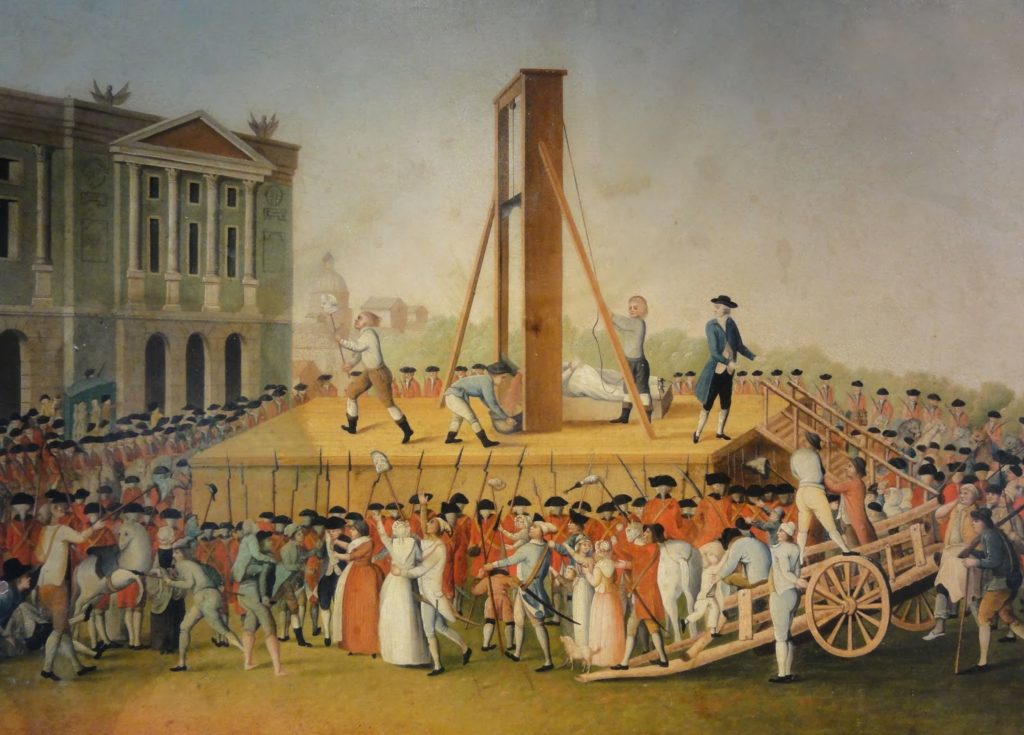

As the cart reaches Place de la Révolution, Marie catches a glimpse of her one-time home, the grand Tuileries Palace, and her face crumbles. Sudden hot tears stream from her eyes and her body trembles. But in a moment she has recovered. She forces the tears back, veils her emotion and steps from the cart with purpose. Draped in a white cotton gown and white cap, she has been stripped of all the finery she was once renowned for, but Marie knows, even without a crown, she is still a queen; that is all she ever was. With her head held high, she moves with majesty towards the guillotine. The time is 12.15pm when she rests her neck upon the block. The blade is released, and in a moment the illustrious and terrible life of the most hated woman in France is ended.

Since her birth, Marie Antoinette had been primed and prepped to become a queen. Born the 15th child of the formidable Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa, the only woman to serve in the role, her mother was strict and distant with her youngest daughter, determined she should serve as a bridge between the two great warring dynasties of Habsburg and Bourbon. Maria was a clever woman, and she ensured that her beautiful young daughter became the talk of the French capital. The French king Louis XV was convinced, and arranged the marriage of the young archduchess to his grandson and heir, Louis XVI.

The two great leaders, concerned with cementing their individual power, had not taken into consideration the compatibility or the happiness of the children involved. The young archduchess was undoubtedly beautiful, with her slender figure and gleaming blonde hair, but she was also incredibly vivacious. Caring little for books and education, she was a thrill-seeker, and although she didn’t know languages or mathematics, she knew people, and was an expert at getting them to do exactly what she wanted. The young dauphin, meanwhile, was a quiet and timid boy. Strictly religious, he read often and engaged in quiet pursuits. He loved deeply, but he feared even more so, and most crucially, he was a man who could be easily convinced by loud, persuasive people – his new wife was one such person.

The moment Marie stepped through the doors of Versailles she was surrounded by courtiers far older and more experienced than her, who opposed everything she represented – an alliance between France and Austria. Marie was denied the common method any young queen would employ to solidify her position – producing an heir – as Louis was unable to consummate the marriage for seven long years. Her awkward and humiliated husband shrank smaller and smaller under the knowing smirks of the members of court, but shrinking was the last thing Marie had on her mind.

Marie dressed for success. She robed herself in a huge array of luxurious silk dresses, placed her dainty hands into scented gloves, stood strong in high heels and literally made herself taller with her towering pouf hairstyle. She broke court traditions, abandoning heavy make-up and replacing wide-hooped panniers with simple feminine dresses that complemented her full figure. Her costume was strategy for survival; it sent a loud and clear message – “I can do exactly what I please” – and this message filtered into her lifestyle. As her husband slept, she partied into the early hours, gossiping with friends and attending masked balls. She commissioned a painting of herself riding in the style of a man and she even dared to own a property independently of her husband. The young Austrian was making waves; if tradition wouldn’t accept her, then she would smash it to pieces.

The older generation at court didn’t like this one bit – a frivolous, air-headed girl they could handle, but an ambitious and stubborn foreign woman who didn’t know her place? That was far more dangerous. Before she had even finished her teens Marie was making enemies. What was originally the gossip of court filtered outside the palace walls and filled the pages of the libelles, the slanderous pamphlets published across France. To the writers and readers of these, the lack of an heir obviously meant that the queen was courting other men, and her excessive wardrobe came across as grandiose at a time when her people were starving. The revolutionary propaganda that was already bubbling leapt upon this image of an idiotic, shameless queen and refused to let it go. Little did Marie know, while she focused on cementing her place as queen, the destruction of the royal authority had already begun, and she was to serve as the centrepiece.

After the royal couple were finally able to produce an heir, the queen transformed from a party girl to a stern, self-controlled woman. But this change came too late; the revolution gaining speed outside the palace walls had already decided exactly what sort of person she was. The country was in debt, huge debt, and it was the common people who were feeling the sting. Marie, deemed responsible thanks to her trivial expenditures, was dubbed ‘Madame Déficit’. This was not without truth – Marie spent more than any other person in France, bestowing her favourites with gifts and reluctant to tax her aristocrat chums. The expenses of court were huge, and outside the people were starving.

But Marie was fighting her own battles. Her husband, after suffering from bouts of depression, had withdrawn his power in government and she was the only one able to cement the authority of monarchy in his place. Despite her own mother’s advice to avoid meddling in politics, the queen emerged as a powerful political force, and without the support of her husband was forced to grapple for the power of the monarchy against an assembly growing less and less faithful.

On the surface she was iron, but underneath Marie was shaken by the uprising outside the palace walls. She had made hasty efforts to reduce her expenditure, stripping her room of her fineries, but these efforts went largely ignored. When she emerged in her box at the theatre, she was hissed at so horrifically by the crowd that she began to completely withdraw from the woman she once was. She stayed away from parties, from balls, even from the king’s council chamber, and devoted her attention to her children, terrified that if she involved herself further, she would be held responsible for tearing France in two.

On 4 June 1789, tragedy struck. The dauphin, Marie’s eldest son and all-important heir to the throne, died. The royal couple were overcome with grief for the child they had anticipated for so long, but the people were not. The death, usually cause for national mourning, was ignored by the people desperate to end the famine that was killing their own children. Marie was outraged, and when demand after demand poured through for reform, she urged the king to remain strong against them. For a woman who believed in the absolute power of monarchy, who had spent all her childhood and adult life in palaces, the revolution opposed and offended everything she believed in and had worked for. Now she was ready to use force to get the rebellious masses to understand.The queen did not understand for one moment the justifications or hopes that underpinned the revolution. All that she witnessed was the brutality and murderous tactics of its leaders, and she wanted to blast every trace of it from existence. What she saw was not liberty, but rebellion and chaos.

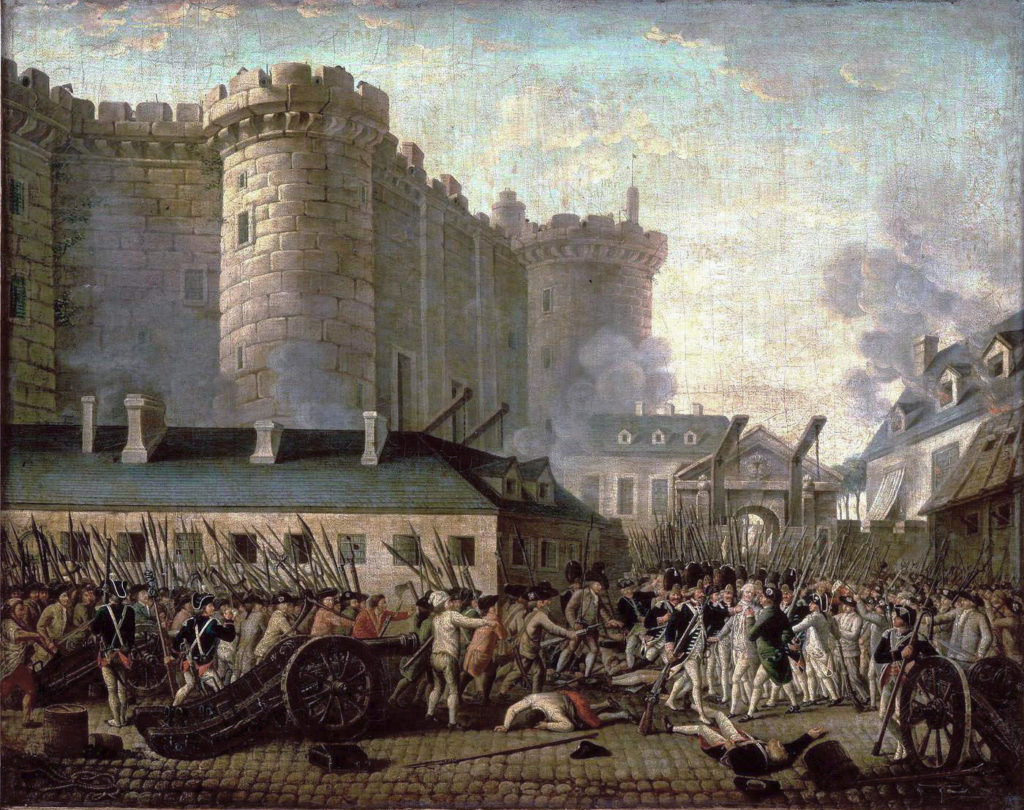

Marie decided that the revolution must be crushed with mercenary Germanic troops. She believed, deep down, that the people were good natured and would respect the authority of the monarchy when faced with force. But she was wrong. As news of an armed attack swept through Paris, the revolutionaries took their cause a step further, stormed the Bastille and turned the streets red with blood.

As royalists fled Paris for their lives, the woman most at risk remained with her husband and was forced to stand by as his power was signed away to the National Assembly that was now ruling Paris. But this was not enough for the outraged population. The king had hoped that by agreeing to demands and staying at the palace in Versailles he could keep a low profile until the revolution died down, but on 5 October a mob of outraged women marched from Paris to Versailles. They had one aim in mind, and navigated their way through the palace to Marie’s private suite. Fuelled by revolutionary passion, they cut down their foes and sacrificed their own lives to confront Madame Déficit directly.

Marie had fled, barefoot and half naked, to the king’s bedchamber, barely escaping with her life. The mob reformed beneath a balcony and their voices rose in unison as they demanded to see the queen. Marie, who had never bowed to anyone she deemed inferior, was humiliated, but had no choice. Taking her young son and daughter with her, she emerged, straight backed and strong against the rabble of revolution. She was not humble, not apologetic, nor begging for mercy, but had the iron will of a soldier facing a firing line. Faced with this defiant, unyielding, prideful woman, the crowd bellowed a cry she had not heard for many years: “Long live the queen!”

However, the cries of support did not continue as the royal family was transported from Versailles to their essential captivity in the Tuileries Palace in Paris. Marie sunk down as she sat in the carriage, hoping to avoid the glare and insults of the uncontrollable mob. She loathed the palace. Though it had housed royalty, she had been forced there against her will and in complete humiliation. She was furious that the entire world would now know that the divine right of kings had been challenged and, like a petulant child, refused to do anything that might improve her popularity.

For Marie, the truth was clear – the mob had won, and she refused to remain a prisoner of a force of chaos. After two painful years of her powers being sapped, Marie had had enough and focused on escaping Paris. In 1791, the royal family, disguised as common travellers, were smuggled away in a carriage. The coach travelled some 200 miles, though it was anything but subtle. The queen had refused to travel without all her comforts, and the heavy, slow carriage with its extra horses attracted attention. Their faces were among the most recognisable in the land, and the escapees were inevitably discovered. Disgraced and humiliated, they were forced to make the long journey back to Paris. Dusty, weary and aged beyond her 35 years, as Marie travelled through the crowds to her prison she was spat on, beaten and pushed by the crowds. The monarchs had chosen to abandon their people, so the people made a decision in kind – the monarchy had to go.

The queen knew it was useless to try to find sympathetic ears in France. With the revolution out of control and the hatred against her reaching fever pitch, she appealed to her powerful relations. She pushed her brother, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II, and his son Francis II to threaten France on her behalf. But this led to France declaring war on Austria on 20 April 1792. Not only was the ‘Austrian woman’ hated, but now she was also an enemy. Foreign armies poured into France, threatening the people that if any harm was to come to the royal family, they would pay with their lives. But this was a crowd as unrelenting as their queen.

Marie’s actions had brought war to France, and the people brought war to her. On 10 August, an armed mob stormed into the palace, forcing the king and queen into a tiny reporter’s box. Under heckles and the glare of the crowd, they stood by helplessly as the 900 Swiss guards charged with defending them were massacred. All their precious objects were gathered and piled on desks as they were forced to listen to the debates that declared a republic and ended the monarchy.

If Marie loathed her imprisonment in the Tuileries, the Temple fortress she and her family were escorted to was another hell entirely. Stripped of all the finery that had for so long defined her, Marie was treated horrifically by her jailers. As well as the constant abuse and insults, they blew smoke in her face and allowed her no privacy. Under such extreme conditions her health deteriorated and she developed tuberculosis. But worse than illness, worse than rags, and worse than jeers, her royal name, her pride and identity had been stripped from her. Royalty no longer, the family was given the name Capet, ending the long line of monarchs that had ruled the country for more than 1,000 years.

In December, Louis, Marie’s ever indecisive and conservative husband, was found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death. A month later he was executed. Although the royal couple had always been a mismatched pair, and rumours of Marie seeking comfort elsewhere may not have been entirely untrue, he had been the father of her children, her companion for more than 20 years and her only security in time of terror and uncertainty. There is no doubt that his execution shocked and saddened Marie to her core.

She had always found comfort in her children, but in July, despite her pleas, her beloved son was taken from her, and in September she was taken from the only family she had left – her daughter and sister in law. She was condemned to a month of horrific solitary confinement in a dank underground cell in the Conciergerie. Under constant surveillance, she had no chance of escape, but she would not have to wait long to discover her fate.

On 14 October, Marie was taken to face her enemies at the Revolutionary Tribunal. The charges against her were more an attack on her person than her politics; the headlines that had filled the libelles were presented as fact. They accused her of organising orgies in Versailles, orchestrating the massacre of the Swiss guards, sending France’s money to Austria and, most appalling of all, sexually abusing her own son. At this she refused to respond, simply uttering: “If I make no reply, it is because I cannot. I appeal to all mothers in this audience.” Her unbelievable defiance and strength despite the horrors she had endured was remarkable, but the verdict had been decided before she even entered the room. Guilty.

In her execution, Marie displayed the courage and markings of a true queen until the end. But that was the problem exactly: she was a queen in every sense of the word. She was born to be a queen, trained to be a queen, had performed her duties as queen throughout her entire life – but France didn’t want a queen. Her lifeless body was dragged from the guillotine and tossed in a cart and her head was thrown between her legs. Her remains were dumped in an unmarked grave, but the memory of Marie Antoinette would live on as France’s hated, but eternal, queen.

An extended version of this feature first appeared in All About History issue 27. Discover the latest issue of All About History here or subscribe now.