The 1550s were one of the most turbulent times of upheaval in English history. Europe was split between the old certainties of Roman Catholicism and the new reforms of Protestantism; England became a divided country. This was most keenly felt in the years 1547-58 when the state religion of the country changed three times. In the middle of this tumultuous decade, an age of kings, came a revolt that threatened the lives of three past, present and future queens. The failure of Wyatt’s Rebellion of 1554 would have profound but unintended consequences for the course of English history.

Although Henry VIII had broken with the papacy and established an independent Church of England, he remained a Catholic and the country largely followed suit. However, his nine-year-old successor, Edward VI, and his governors sought to change that.

Despite being a child, Edward was a zealous Protestant and under his rule England became a Protestant nation for the first time. While this may not seem that important today, in the 16th century it was a new world order. Catholicism had been uncontested for over 1,000 years and its changing character didn’t just change people’s spiritual beliefs but also their sense of national identity. The independence of the Church of England engendered a new English nationalism and with it a heightened fear of foreigners, particularly Catholics.

Nonetheless, Edward’s Protestantism did not reflect the beliefs of the generally conservative population and many remained Catholics, including Edward’s older half-sister Princess Mary. Mary was half-Spanish, devoutly Catholic and politically close to her cousin Charles V, king of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor. Charles was an inveterate opponent of the Reformation and consequently Edward distrusted Mary – but he had a problem. Until he married and produced an heir, Mary would inherit the throne and could not be ignored. The two warily coexisted until the political situation dramatically changed when Edward fell ill and died at the age of 15 in 1553. There was suddenly a power vacuum to be filled.

Mary I, known as ‘Bloody Mary’, painted at the age of 28

Before he died, on 6 July, Edward had barred (possibly under duress) Mary and other his half-sister Elizabeth from the succession. Although Elizabeth was a Protestant, her father, Henry VIII, had declared her illegitimate and Edward upheld that principle. Edward and his regent, the Duke of Northumberland, ‘agreed’ that his cousin Lady Jane Grey should inherit throne. Jane famously ruled as queen for only nine days between 10-19 July with Northumberland running the government. Mary was quick to act and in a popular movement she was declared queen by the Privy Council and entered London on 3 August. Jane was charged with treason and imprisoned in the Tower of London while Northumberland was executed.

For the first time in its history there was an undisputed Queen of England, but Mary immediately sought to undo the reforms of her father and brother and changed the nation’s religion back to Catholicism. This might have been acceptable to the silent majority who were still secret Catholics, but the Reformation had stirred up nationalist sentiments against foreigners and this caused significant problems in Mary’s next political move: her forthcoming nuptials.

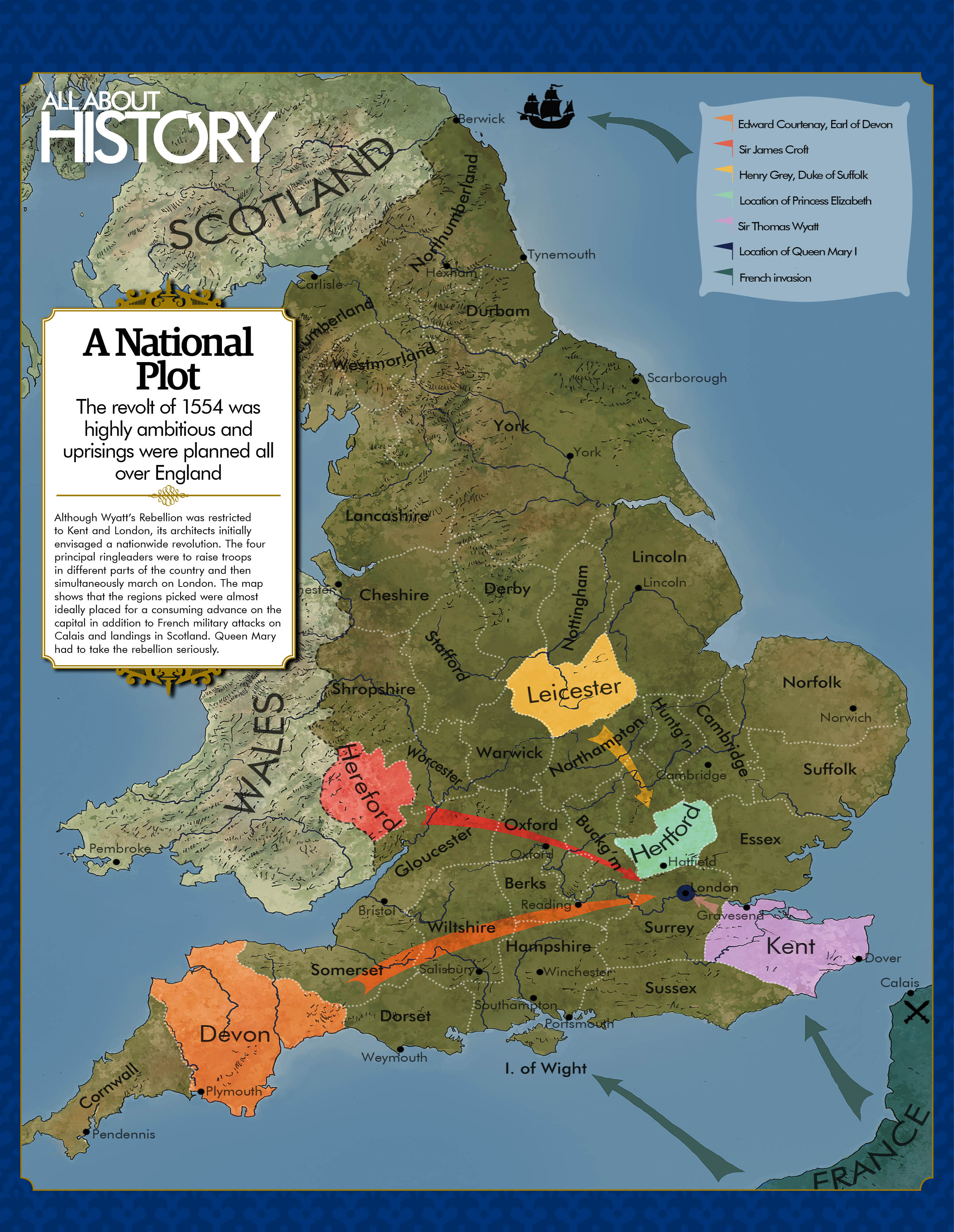

Mary felt that to spiritually secure her kingdom she had to marry a fellow Catholic and to produce Catholic heirs. On 16 November 1553, a Parliamentary delegation had urged Mary to marry an English husband but the queen had her sights set overseas and rumours abounded that she was going to marry the zealously Catholic Philip II of Spain, the heir of Charles V. On 26 November, prominent men met at the house of Jane’s father, the Duke of Suffolk, and planned to prevent a foreign royal marriage. Among the conspirators were Sir James Croft, Edward Courtenay, earl of Devon, Suffolk and Sir Thomas Wyatt.

Devon was chosen as the figurehead of a proposed national armed rebellion that would converge upon London. The precise aims of the rebellion are unclear; it has been hypothesised that they simply wanted to stop the Spanish marriage, or to depose Mary and install Elizabeth as queen, with Devon as her prospective husband. The latter option assumed there would be popular support for a Protestant restoration but the plotters themselves were uncertain reformers. Of all of them, only Edward VI’s clerk of the Privy Council, William Thomas, was a committed Protestant; this ambiguity meant the coming rebellion would be nationalistic in tone.

Of the conspirators, it would be Sir Thomas Wyatt the younger who would become the most prominent. Born circa 1521, Wyatt emerged as a soldier during the last years of Henry VIII’s reign. He had been imprisoned for a month in 1543 for taking part in an aristocratic rampage in London but the government put his aggressive behaviour to good use. In June 1544, he was commissioned to lead 100 men against France. He was promoted to captain of the Boulogne garrison and was knighted in 1545.

Thomas Wyatt the Younger, the leader of the pack

Wyatt was renowned as a brave soldier and skilled in discipline and fortifications. In an attack on Hardelot Castle, he personally stormed the first gate, broke open the door, killed one of the watchmen and captured another two. He was praised for his, “hardiness, painfulness, circumspection and natural disposition to war,” but there was an early warning that he was hotheaded and had a weakness for “too strong opinion.”

For the rebellion, Wyatt was chosen to recruit soldiers in Kent, alongside other insurgencies in the country. Courtenay was to raise troops in Devon; Sir James Croft in Herefordshire; Suffolk in Midlands counties such as Leicestershire and Warwickshire. Once all the groups had been assembled the plan was to start the rebellion on 18 March 1554, then converge on London. The French ambassador was also involved and if it went well he promised money, equipment and, most importantly, soldiers who would attack the English colony of Calais and also land a force on the east coast of Scotland. This was by no means an amateurish plot but it almost immediately began to fall apart.

Courtenay lost his nerve and didn’t travel to Devon to incite rebellion, choosing to remain at court. Word of the plot reached the Lord Chancellor Bishop Stephen Gardiner who interrogated Courtenay. The hapless earl gave away most of the details. The rebellion was now betrayed and most of the plans never took place with the notable exception of Thomas Wyatt.

Wyatt began in Maidstone, Kent on 25 January 1554, much earlier than the proposed start of the uprising but in light of Courtenay’s betrayal Wyatt felt there was no time to lose. He issued a proclamation that was read out in other Kentish towns that said, “For as much as it is now spread abroad and certainly by the Lord Chancellor and others of the queen’s pleasure to marry with a stranger we therefore write unto you, because you be our friends, neighbours and Englishmen, that you will join with us, as we will with you unto death in this behalf.” It continued, “We seek no harm to the queen, but better counsel and counsellors. Herein lie the health and wealth of us all.”

Wyatt then proceeded to officially raise his standard and made his headquarters at Rochester. The government quickly heard of the Kent uprising and levied 600 troops in London to quell under the command of Thomas Howard, the octogenarian duke of Norfolk. At first Norfolk’s troops (known as ‘Whitecoats’) defeated a small rebel force at Wrotham but the next day his own men deserted him at the bridge into Rochester, claiming sympathy with the rebels and declaring, “We are Englishmen.”

A list of arms doled out to put down Wyatt’s rebellion.

The defection of the Londoners boosted Wyatt’s confidence and his rebel numbers to between 2-3,000 men, and he planned to slowly march on the capital. Wyatt’s army entered Southwark on 3 February and paused there for three days but the moment when events appearing to be turning in his favour was when it began to unravel.

Most of Wyatt’s allies came from a limited support base in Kent and, although much of the gentry were quietly sympathetic to his aims, they did not provide the necessary support while Queen Mary was gathering strength. She had been proactive in defending her position and went to London’s Guildhall to exhort the Londoners to come to her aid and 20,000 men volunteered to act as a militia against the rebels. This was far more than Wyatt’s force and he now faced a dilemma. Southwark was at the southern end of London Bridge but the bridge itself was strongly defended and all boats were kept on the north bank. At the same time cannon fire from the Tower of London was damaging homes, making the inhabitants restless.

On 6 February, Wyatt moved away, crossed the bridge at Kingston and entered Hyde Park the next day where he had a minor skirmish with government forces. From the park the rebels moved east passing Charing Cross where some were beaten off and then along Fleet Street. As they marched they loudly claimed loyalty to the queen, which was met with bemusement by the citizens who looked out of their doorways. The government troops deliberately let Wyatt march on, luring him into a trap. At Ludgate the soldiers of Lord William Howard finally stopped the rebels and Wyatt was forced to retreat towards Temple Bar to face the cavalry of the earl of Pembroke.

After several fights a herald appeared and asked Wyatt to surrender rather than cause more bloodshed. Wyatt, vastly outnumbered and betrayed, conceded and was taken to Whitehall, and then on to the Tower of London. About 40 rebels had been killed.

Although the rebellion was over the political ramifications intensified, with the focus now turning to Lady Jane Grey. Her father, the duke of Suffolk, had been one of key conspirators in the uprising and his actions sealed her fate. Although she had taken no part in the revolt, her existence as a figurehead for Protestant discontent made her dangerous to the Catholic state. Mary sentenced her cousin to death. In a parting blow, she attempted to force Jane to convert to Catholicism to save her soul but the devoutly Protestant Jane refused.

On 12 February 1554, both Jane and her husband Guildford, the son of Northumberland, were executed on Tower Hill. Jane suffered the horror of seeing her husband’s decapitated corpse return from the scaffold before being beheaded. When she was blindfolded she struggled to find the block but she died bravely with her last words being “Lord, into thy hands I commend my spirit.” The killing of this intelligent 16-year old was a terrible act of judicial murder.

The attention was now on Princess Elizabeth. On the same day of Jane’s execution, Elizabeth was transported to London and arrived on 23 February. Her situation was dire as the conspirators had planned to marry her to Courtenay. The government now tried to ascertain her true role in the revolt and on 18 March she was taken from Whitehall and imprisoned in the Tower. Mary was now being advised that her half-sister was too dangerous to live and Elizabeth was lodged in the same rooms as her doomed mother Anne Boleyn had been before her execution. Her survival looked doubtful, but she was inadvertently rescued through the actions of Thomas Wyatt.

Wyatt had also been committed to the Tower and was tortured for information. He denied that he sought Mary’s death and that his sole intention was “against the coming in of strangers and Spaniards and to abolish them out of this realm.” Crucially he denied that Elizabeth had been involved in the plot.

Having been sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered Wyatt was executed on 11 April, but before he died he exonerated Elizabeth and the hapless Courtenay from any wrongdoing: “Whereas it is said that I should accuse my lady Elizabeth’s grace and my lord Courtenay; it is not so, good people. For I assure you neither they nor any other was privy of my rising before I began. As I have declared to the queen’s council. And this is most true.” After the execution many dipped their handkerchiefs in Wyatt’s blood and his head was stolen as a martyr’s relic.

Wyatt’s last words saved Elizabeth from a fate that would’ve changed history. Although she was still under great suspicion, the government could find no explicit evidence against her. Elizabeth was removed from the Tower on 19 May and, although she was kept under house arrest, her life was spared. Others were not as lucky. Like Elizabeth, Courtenay was spared, but nearly 100 other rebels were executed as traitors. Most were hung, drawn and quartered.

On balance the rebellion was a complete failure – but it had almost succeeded. If the Londoners had supported Wyatt, Mary could have been deposed and Elizabeth enthroned. The charismatic Wyatt and the xenophobic feelings of the population could have made this possible. As it was, Mary married Philip II of Spain on 25 July, but she died in 1558 without an heir, and it was the Protestant Elizabeth who became queen despite her sister’s very best efforts.

Although Wyatt had arguably put her life in danger, his personal intervention ensured that Elizabeth did not suffer the same fate as Lady Jane Grey and consequently the course of English history was changed forever.

To discover more thrilling stories from the past, pick up All About History magazine.