196 years before Charles Dickens’ festive tale of humbug was published, Oliver Cromwell sealed his reputation as Britain’s foremost Scrooge when parliament, under his influence, outlawed Christmas.

But banning Christmas wasn’t just a symbolic act of parliament. The English Civil War was drawing to a close and Parliament was overrun with puritans who believed Christmas was ‘Popish’ so in 1647 they made celebrating the festival a punishable offence.

During the Interregnum the government went to great lengths to try to suppress the celebrations and enforce the new laws. Ministers who preached on Christmas Day were arrested and shops were supposed to open up their doors. In Leicester the local free school was ordered to rearrange its holidays so that they occurred every quarter rather than at Christmas and at Easter: imagine having to go to school on Christmas day! Puritans also set about trying to delegitimise Christmas through scripture, arguing vehemently that Christmas had been appropriated from the Roman festival of Saturnalia, an issue Matt Salusbury considers here.

But not everybody was content to accept Parliament’s decision…

Riots broke out, particularly in Canterbury where for weeks pro-Christmas rebels controlled the city, decorating churches and demanding a church service on Christmas day.

Journalists ridiculed the notion that Christmas had been banned. In 1652 The Faithful Scout newspaper mocked those who thought that roast beef was ‘anti-Christian’, mince pies were ‘relics of the whore of Babylon’, plum pottage was ‘mere popery’ and geese and Turkey ‘marks of the beast’.

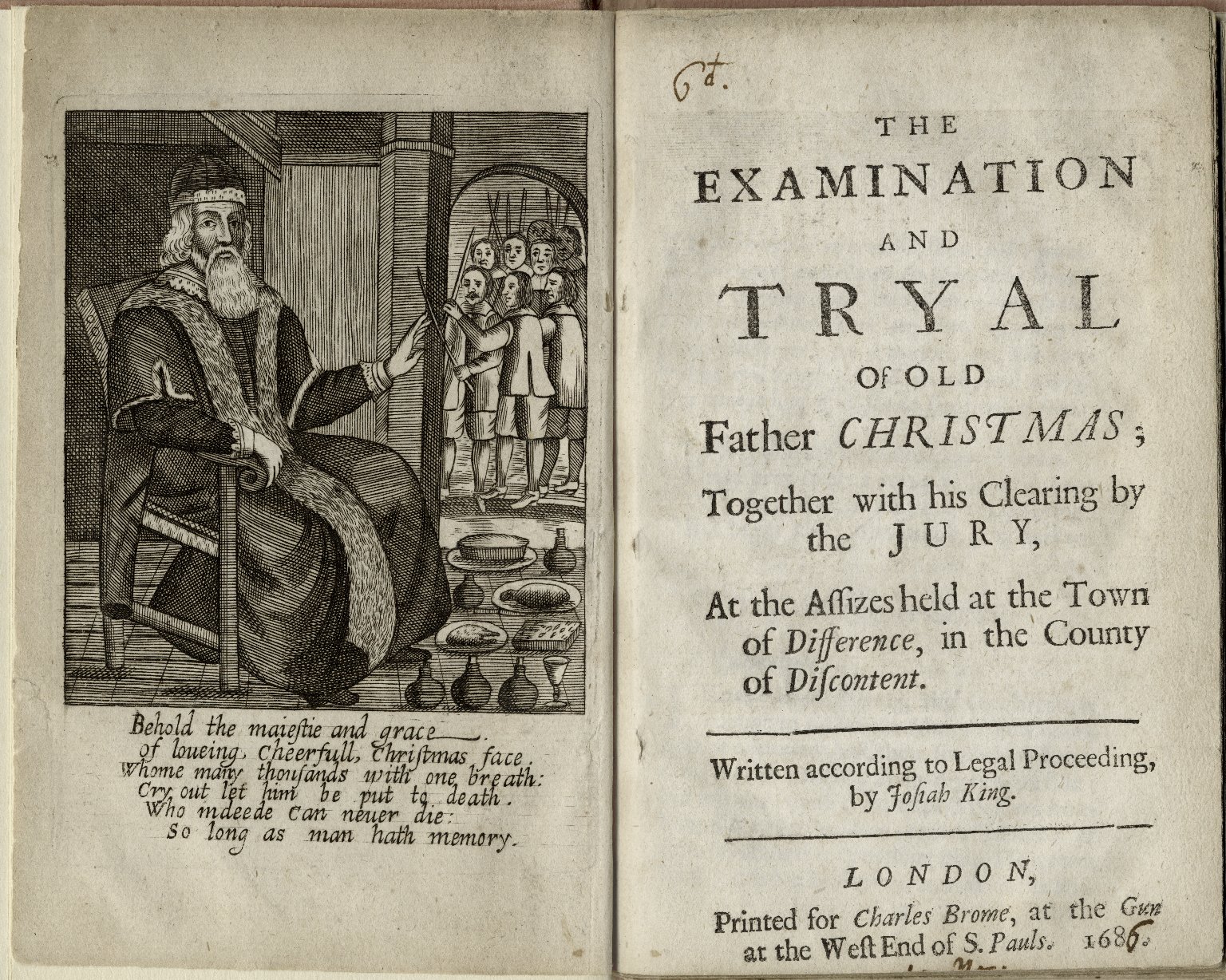

Royalist poet John Taylor published pro-Christmas works such as The Complaint of Christmas which imagines a real life Father Christmas visiting England and being somewhat disappointed. In a similar work, The Vindication of Christmas, Taylor imagines Father Christmas visiting Devonshire farmers on Christmas Day but this time he is pleased by what he sees:

‘Some went to cards, others sung carols and pleasant songs… the poor labouring hinds and maid servants with the ploughboys went nimbly dancing; the poor toiling wretches being glad of my company because they had little or no sport at all till I came amongst them…’

The literature of the day reflected the reality of the national mood. Most people had not given up believing in the idea of Christmas, the celebrations had simply gone underground. Indeed there is evidence of clandestine Christmas celebrations throughout the 1650s.

Parliament had tried to turn 25 December into a normal day by insisting business carry on as usual and they led by example, sitting on Christmas Day in 1656 and staging a debate to reinforce their opposition to the festival. The debate is evidence that the Puritan establishment were concerned that the law was not being enforced. Luke Robinson, MP for Yorkshire and Scarborough, complained that he could not get any sleep for ‘the preparation for this ‘foolish day’s solemnity’. Another MP claimed that ‘One may pass from the Tower to Westminster and not a shop open, nor a creature stirring.’

The diarist John Evelyn gives us a great account of the dangers involved with being a pro-Christmas dissident. He wrote that on Christmas Day 1652, although he could find ‘no sermon anywhere’ with ‘no church being permitted to open’, he simply observed the occasion at home before heading to Lewisham the following day. Here he managed to hunt down ‘an honest divine preached’. He tried again in 1653, 54 and 55 to no avail. In 1656 Evelyn did manage to find solidarity at a certain Dr Wild’s lodgings where he received communion and ‘rejoiced to find so full an assembly of devout and sober Christians.’ On Boxing Day he even invited his neighbours and tenants over ‘to preserve hospitality and charity’.

The following year, 1657, however, Evelyn would not be quite so lucky. He found a service in Exeter House Chapel, on the Strand in London, but as the sermon ended and the preacher, Mr Gunning, was giving out Holy Communion, the church was surrounded by soldiers. Evelyn, with others, was kept under lock and key in the church until a local colonel arrived from Whitehall to interrogate him. Evelyn was asked whether he was praying for Charles Stuart to which he replied he was praying for all ‘Christian kings, princes and governors’. Eventually, ‘finding no color to detain me,’ Evelyn writes, ‘they dismissed me with much pity of my ignorance. These were men of high flight and above ordinances, and spoke spiteful things of our Lord’s nativity.’

It is clear there was also considerable Christmas cheer in Plymouth. Enough, at least, for two Quaker women, Margaret Killam and Barbara Patison, to warn of an excessive drinking culture and the ‘great doings at houses called Gentlemens houses’ in their 1656 tract, A Warning from the Lord to the Teachers and People of Plimouth. The town of Northampton was also known to have been a focal point for Christmas gatherings.

It wasn’t until Charles II was resorted as King in 1660 that the Christmas rebels could resurface once more as a more liberal age began.

For more on curious Christmas traditions, pick up the new issue of All About History or subscribe now and save 25% off the cover price.

Sources

- B.Capp, England’s Culture Wars: Puritain Reformation and its Enemies in the Interregnum, 1649 – 1660 (Oxford University Press, 2012)

- C.Durston, The Puritan War On Christmas, History Today, 35, 12, 1985.

- J. Evelyn, Diaries Volume 1, edited by William Bray (M.Walter Dunne, 1901)

- M. Killam & B. Patison, WARNING FROM THE LORD to the Teachers and people OF PLIMOVTH (1656)

- http://www.historyextra.com/feature/no-christmas-under-cromwell-puritan-assault-christmas-during-1640s-and-1650s