Mention the plague of 1665 and most minds will jump to the Great Plague of London. The pandemic notoriously wiped out a quarter of the city’s population before it was then engulfed by the Great Fire in September 1666.

While many remember the plague as something exclusive to London’s city walls, in reality this deadly infection wreaked havoc up and down the country for centuries. About 150 miles north of London, the fate of Eyam was sealed the moment a bundle of cloth carrying infected fleas arrived from the capital.

What makes Eyam’s story stand out is the reaction of its residents. In order to prevent the spread of infection to neighbouring towns, the picturesque Derbyshire village quarantined itself and, in doing so, condemned itself to the deadly pandemic.

George Viccars was the first to die. The tailor’s assistant came into contact with the fateful insects while hanging up the cloth and after a matter of days, on 7 September 1665, the Eyam plague had claimed its first victim.

Viccars’ name could easily have been forgotten had he died of anything else, but by the end of the month approximately six more villagers, all living nearby, had passed away from similar causes. This included the Thorpe family’s 12-year-old daughter, Mary. The fear and panic must have been tangible as the reality of the situation dawned on the villagers.

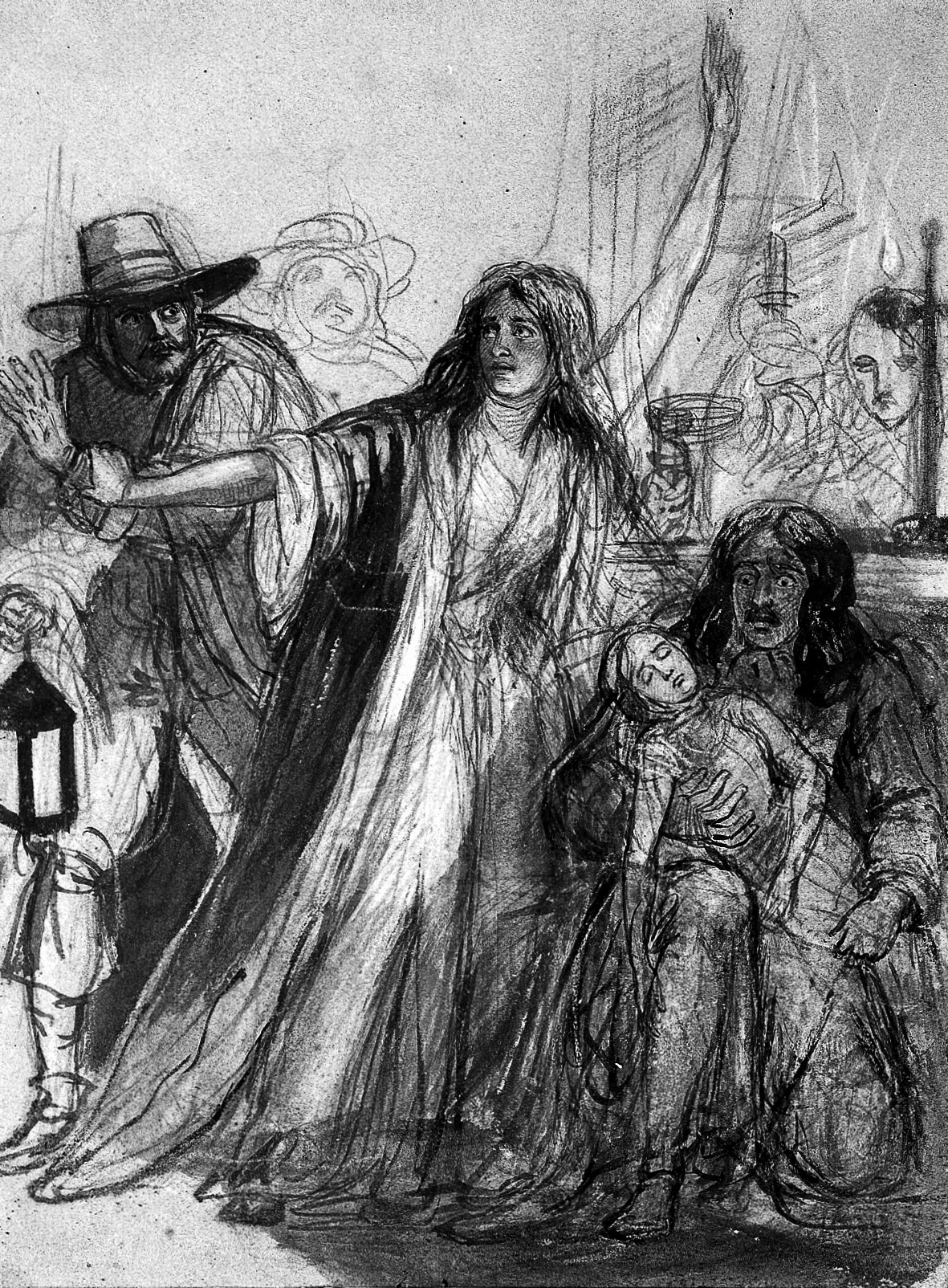

“They were well aware of the perils of the plague […] but it wasn’t until the 19th century that the source of the plague was discovered,” explains local historian Francine Clifford. Without a solid scientific understanding, people turned to the only trusted source: religion.

“There were lots of theories”, she says. “But general consensus was that the plague was an invisible miasma that descended upon a district, sent by God as a punishment for sins.”

It makes sense that, in pious communities, minds would jump to stories of biblical plagues. Of course, as the death toll grew – the Cooper, Hadfield, Syddall and Thorpe families being the worse hit – the village turned to the church for answers.

Residents’ first instinct must have been to flee. However, with little to no help from neighbouring towns who feared contamination, this wasn’t always a viable option. In fact, nearby Sheffield was said to have barriers and guard posts during the time of plague to keep infected strangers away.

That’s not to say everyone in Eyam stayed. As Clifford tells us, “When it came to escaping, only the more affluent people could afford to go, those who had the means to support themselves and their families after leaving their livelihoods and homes behind.”

Such families included the Bradshaws of Bradshaw Hall and members of the Furness family, who fled to accommodation elsewhere. For the most part the villagers, many working as lead miners and farmers, couldn’t afford to abandon their only source of income and shelter.

They had the time to flee too, because while the plague arrived in September 1665 the quarantine wasn’t imposed until June the following year. This delay is due to the considerable drop in plague-related deaths during the winter months.

“They knew the plague was a summer disease and thought the ice and snow of a Derbyshire winter would kill the miasma off,” Clifford explains. “They thought if they could get three weeks without anyone dying of the plague then that’d be the end.”

Hopes were high as May brought very few deaths, but the plague hit back hard in June 1666, spreading like wildfire and wiping out entire families. Village authorities were forced to act.

The rector William Mompesson held little clout in the village. He had only held the position for a couple of years, was an outsider and was young, at 28. Even more challenging was the fact that a previous rector Thomas Stanley still lived in Eyam and, as well as having more experience, commanded the respect of the villagers.

The position must have been a tough gig. Fortunately, despite the tensions, the two men worked together – combining Mompesson’s authority and Stanley’s amiability – to come up with a plan.

To prevent the plague spreading across Derbyshire, they concluded Eyam would be cut off from the outside world until the infection had run its course. Furthermore, there would be no more churchyard burials – people were instead advised to bury their dead as quickly as possible – and church services would be held outside, mostly at the Cucklett Delf where families could stand safe distances from others.

The Earl of Derbyshire, from the nearby Chatsworth Estate, wholeheartedly supported the decision, offering to send much-needed food and supplies. During the cordon there were several ‘dropping points’ around the village’s border where goods and money were exchanged. These points, such as the Boundary Stone and so-called Mompesson’s Well, often had holes filled with vinegar, which was believed to decontaminate money.

Reaching its peak in the heat of July and August, the plague raged through Eyam with August alone seeing an alleged 78 deaths. Whole families were lost, including the Thorpes of whom all nine died, and burying loved ones became a daily occurrence. The Riley Graves, still standing today, is a small private cemetery where Elizabeth Hancock is said to have buried her husband and six children by herself.

Death must have hung in the air like fog and by the time the last plague victim, Abraham Morten, was recorded on 1 November 1666, 260 Eyam residents had died of the vile infection.

Population numbers from before the plague vary – accounts claiming anything from 350 to 800 – but even the more generous figures would mean the village lost almost a third of its total. That’s more than double the known mortality rate experienced in London.

In the years that followed, once assured of its safety, families living away or camping in the fields began to return. According to Francine Clifford, records from 1670 show that there were 186 households – 26 more than before the plague – so life was getting back on track.

“It would have been a traumatic time,” Clifford claims. “But they would have had to pick themselves up, dust themselves off and get on with it.”

Now a buzzing little village, Eyam feels like a piece of living history. Plaques show the houses where the likes of George Viccars and the Thorpe family lived and died. While relics, such as the Boundary Stone and the Riley Graves, stand as a reminder to residents and tourists of the extreme measures the village’s ancestors took to protect neighbouring towns from the deadly plague.

For more on the triumphs and tragedies of the Early Modern world, subscribe to All About History for as little as £26.