Witch hunting was old by the time Great Britain erupted into the Civil Wars of 1639-1651, but this existential clash between royalists and parliamentarians amid a swirling miasma of sectarianism and suspicion, resulted in a fresh flowering of superstitious barbarity. Behind the frontlines of the conflict in the puritan stronghold of East Anglia, Matthew Hopkins, the self-proclaimed Witchfinder General, and his colleague John Stearne dispatched an estimated 300 people to the gallows between 1644 and 1647 for their alleged covenant with the devil.

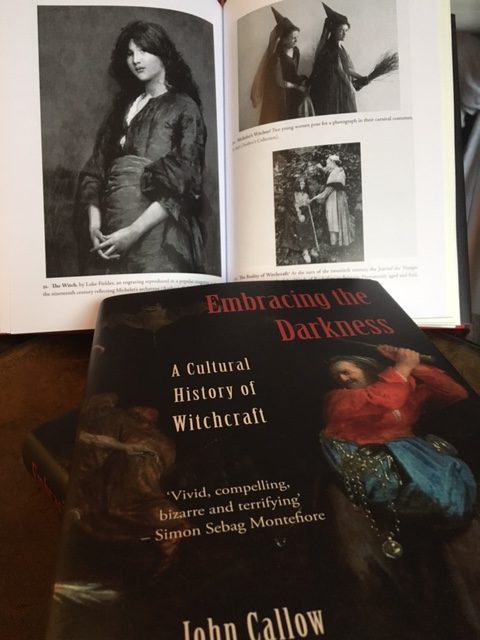

It was the largest outbreak of witch hunting in English history, a unique product of fear, war, and the breakdown of civil society. With his new book Embracing the Darkness: A Cultural History of Witchcraft tracing the rise and the evolution of witch, we spoke to Dr John Callow to get a sense of the context behind Matthew Hopkins’ bloody trail of terror, and its long legacy that stretched from Salem to Wicca to 20th century gothic horror.

Is there a direct correlation between the depiction of Royalists as demonic or licentious (such as Rupert of the Rhine), and the fear of witches that exploded in East Anglia?

This is certainly what historians now think, largely as the result of ground-breaking work by Professor Mark Stoyle. The Civil War militarised and brutalised English society to an unprecedented extent and, at the outbreak of the war, Prince Rupert seemed to embody all that was to be most feared: the ethos of the ruthless, swaggering, foreign professional soldier, hardened to looting and the massacres of the Thirty Years’ War. As a consequences, the stories that gathered around Rupert from 1642-44, concerning his employment of familiar spirits – namely his great white dog ‘Boy’ – witchcraft and shape-shifting; were easily projected onto village women, once the prince’s military reputation was shattered at Marston Moor.

What role did the fear/suspicion of Catholicism play in the shaping of this image?

The idea of the ‘other’ – the fearful, corrosive outsider – is a common theme in most witch persecutions. Minorities are always at risk. In Counter Reformation Germany, the Protestant was often identified as the would-be witch; in the Spain of the Inquisition, it was the Jew; in 15th century France it was Joan of Arc as the liberated woman who adopted man’s clothing. In the same way, deadly folktales about Cardinal Wolsey – once a local boy made good, turned after his fall from power into a ‘witch master’ – began to transfer themselves onto Prince Rupert. The irony, here, is that Rupert was a dedicated Calvinist; a temperate drinker and very far from being a rake. It was his uncanny good fortune in battle – just like Wolsey’s sudden rise to power – that appeared suspect and unnatural. It was this that equated both the Catholic Cardinal and the Protestant Prince, in the eyes of their detractors, with the devil.

Were there similar outpourings of Satanic panic during the Civil War, or is the trail of destruction left by Matthew Hopkins an anomaly?

After a period of marked decline from the 1620s, the Civil War re-ignited an interest in witches and a burgeoning, popular literature about their fearful magic. After the deadly hatred surrounding the last of the Lancashire witch trials had died down, the figure of the witch had often been viewed by dramatists as a comic, or pitiable one. The trouble was that these jokes and the sometimes entirely fictionalised accounts of their careers could – and often were – taken in deadly seriousness at times of crisis and societal breakdown. The hurried reprinting of earlier witchcraft tracts and trial accounts during the 1640s-50s created conditions in which persecution could flourish.

Beyond any doubt, the East Anglian outbreak of 1645-47 was the most dramatic and deadly cycle of witch-hunting ever undertaken in England. But Hopkins and his companion, John Stearne, were the symptoms of this canker rather than the cause. The collapse of traditional authority, a vacuum at the heart of the legal system, and an upsurge in popular fears about the efficacy of witchcraft created the climate in which Hopkins and Stearne might flourish. Certainly they were not the only witch-hunters operating during the period. The trials did not stop with Hopkins’ death in 1647 but radiated out to Kent in the 1650s. As late as the 1680s, the services of witchfinders were being sought and contracted by concerned citizens in the Devon boom-town of Bideford when accusations of witchcraft, once again, surfaced. It was not until the 18th century, with the acceptance of Cartesianism, a transcendent notion of God, and the rise of the philosophes that the devil was pushed to the margins and the witch was consigned to the pages of the story book.

How did the East Anglia witch trials inform future witch panics, such as Salem?

Despite a gap of almost half a century, Puritanism, a society under considerable stress and a desire for religious conformity, provided common links between the largest witch-hunt in English history (in East Anglia in 1645-7) and in North America (at Salem in 1692). Furthermore, Massachusetts had been a magnet for settlers from the same Eastern counties in England that had been at the centre of the earlier trials. Ideas as well as commerce flowed freely, and surprisingly, freely between old and New England and figures, like John Hathorne (1641-1717) who presided over the Salem trials, spanned both lands and were rooted in a sense of an imminent, judgmental God and a prescient, corporeal evil that continually sought to undermine His world and work, through the devil and witches.

How much of the contemporary pop culture imagery of the witch can be traced back to this period?

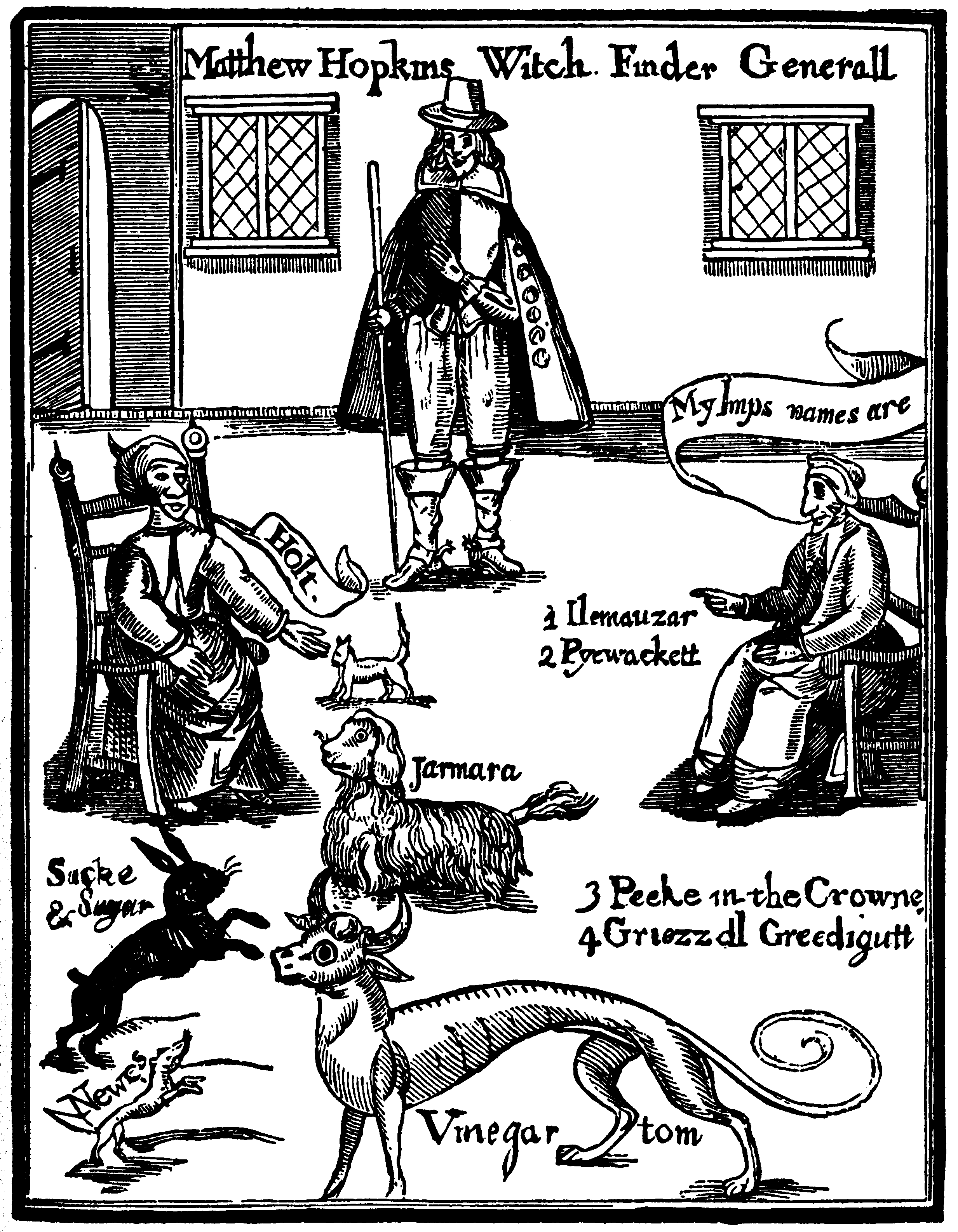

There is no doubt that the modern image of the witch – crooked, old and poor, complete with a pointed hat, broom and black cat – stems from the mid-17th century. You only have to look at the title page of Hopkins’ ‘Discovery of Witches’ to see the stereotype, seated around the hearth and surrounded by her quarrelsome familiar spirits. The Classical witch who – like Circe – was often young, beautiful and adept at love magic – had been progressively debased and – quite literally – demonised by a succession of artists over the course of the 16th century. Thus, by the 1640s, a fresh pamphlet literature abounded with images that transposed the witch from a mythic past into the reality of the present. The witch could, now, live next door; sour the milk, sicken the livestock and kill the babe in the cradle. That is what made her so dangerous, fearsome and compelling.

Did Matthew Hopkins have a role in the the popular imagination before Tigon’s 1968 film ‘Witchfinder General’ or does that deserve credit for raising his pop-culture profile (for lack of a better word)?

There’s no doubt that Vincent Price’s portrayal of Hopkins – as sneering, subtle and insidious – defined the image of the witchfinder for a whole generation. When the BBC came to make its own drama about the English Civil War, ‘By the Sword Divided’ in 1985, it’s version of the itinerant fanatic was virtually identical. In a similar fashion, the sheer theatricality of Price and the edginess of Michael Reeves’ script lent itself, perfectly, to heavy rock and metal in the 1970s-80s, with bands like Cathedral and Saxon referencing the movie, and another group taking not only its inspiration – but also its name – directly, from ‘Witchfinder General’. Their first single ‘Burning a Sinner’ demonstrates the pervasiveness of the myth – contrary to all the historical evidence in England – that witches Walways burn, rather than hang.

This said, Hopkins has a counter-cultural appeal that predates the film. Gerald Gardner – the father of modern witchcraft – first approached Margaret Murray and the Folk-Lore Society with a cabinet of curiosities that claimed to contain Hopkins’ staff and a witch’s ‘Moon Dial’. Within this context, it’s ironic that Gardner – who did more than anyone else to remove the sulphur of Satanism from witchcraft – began his magical career with a recourse to the career of the greatest demoniser of witches that England had ever seen.

Embracing the Darkness: A Cultural History of Witchcraft by John Callow is available now. For more gruesome curios from history, subscribe to All About History for as little as £26.