The Royal College of Physicians is commemorating the 350th anniversary of the Great Fire of London with a new free exhibition, ‘To fetch out the fire’: Reviving London, 1666 which explores medical treatment of the period through original artefacts, remedies, portraits and documents, as well as the destruction of the original Royal College building and its rebirth for the new London. Historian Berwyn Kinsey sheds some light on how physicians and folk healers treated casualties left in the conflagration’s wake.

When the casualties of 1666 started to appear, who would have been our typical “first responder”?

At the time of The Great Fire, though many parishes and wards and the City authorities had nominated firefighters, there was no over-arching organisation or recognisable fire brigade in place. This was is in spite of the fact that the great diarist Samuel Pepys, who lived through the period, recorded 15 other significant blazes in London and they were clearly a common occurrence.

Likewise, though London had some great hospitals and was fast growing as a centre for medical study and learning, there was no ambulance service or anything like a system of clinics, GPs, accident and emergency centres or the kinds of facilities and professionals that we would expect today.

In fact, most people would be amazed at how few fully qualified doctors there were in the City. During the Great Plague just the year before – only two members of the Royal College of Physicians had remained in London to administer to the sick in an official capacity – the others fled, along with wealthy to the safety of the countryside. Though additional doctors remained in voluntary roles, they were supported by other medical professionals, the same medical professionals who probably acted as ‘first responders’ in during the Great Fire of 1666.

These included apothecaries: who not only made and mixed medicines, but in reality also prescribed them and took a lead in caring for patients of ‘the middling sort’ who often couldn’t afford the high fees charged by the physicians.

Likewise, surgeons, who were still members of the same city guild as barbers at the time, and did not possess university degrees, would have provided basic medical care beyond what we would think of as surgery today. Then there were nurses, largely untrained and often viewed with suspicion by the ‘medical professionals’, ‘quacks’, ‘herbalists’ and perhaps most interestingly lay people with specific medical knowledge.

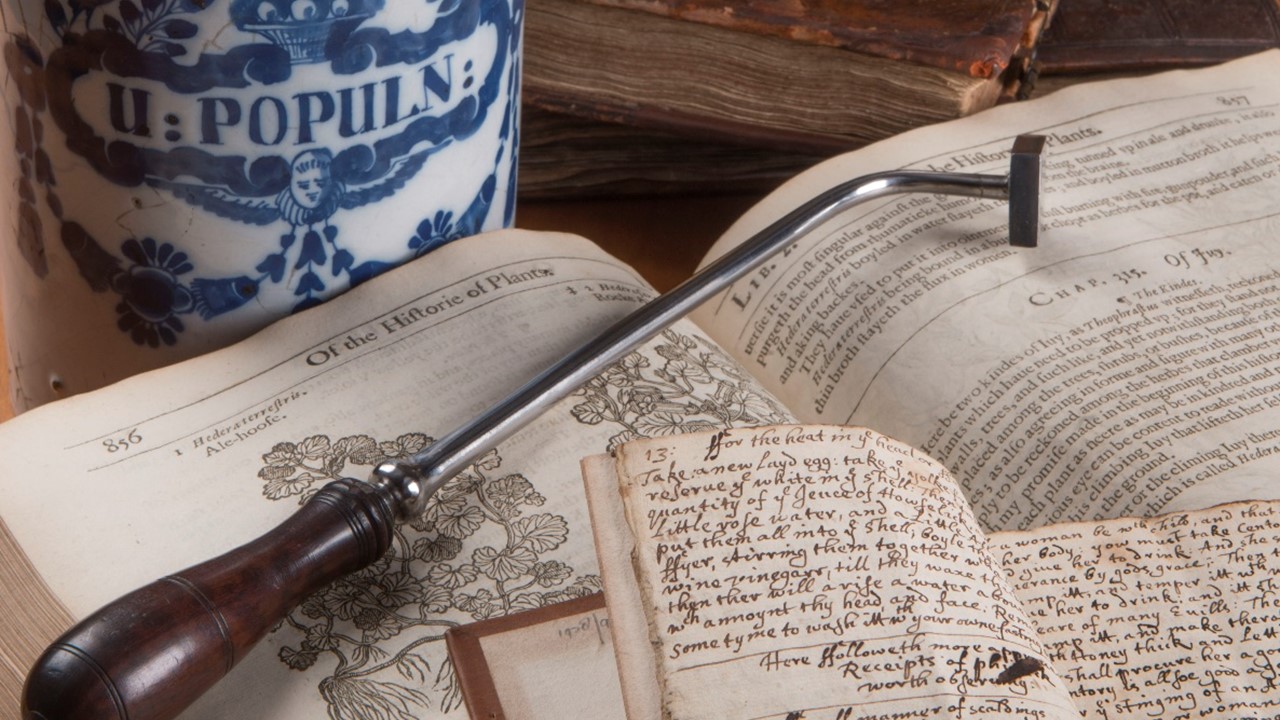

The recipe books on display in the exhibition ‘To fetch out the fire’ at the Royal College of Physicians, feature original 17th century recipe – or ‘receipt’ as they were then known – books containing many recipes for treating burns from salves to poultices, dressings to ointments. They were owned by ordinary households in the main and often written by the women of the house, indicating that practical medicine, like laundry and baking were part of the responsibility of the ‘housewyf’.

So, in reality, in the midst of the chaos, first responders and first aiders could and would have been anyone at hand with strength of mind and body to assist with evacuation (Pepys writes of “here and there, sick people carried away in beds”) and the administration of the cures of the time, regardless of whether they were a professional or not.

How would the patient find his way to a doctor and would they be paid on the spot? It’s tempting to imagine some of them out in the streets touting for business…

Actual doctors – or physicians as they were more commonly known at the time – would have been few and far between and given how in demand they would have been and their status as learned gentlemen they would have been unlikely to have touted the streets for trade.

Though accounts are very few and far between, we believe that those physicians who continued to practice – it’s important to remember that many would have suffered loss of homes, possession and perhaps life too – either continued to work with their own established and affluent clients or through the hospitals that survived.

From the other great diarist of the time John Evelyn we know that some of capital’s medical infrastructure was destroyed as the flames engulfed “the churches, public halls, Exchange, hospitals, monuments, and ornaments, leaping after a prodigious manner, from house to house and street to street.”

However two of the city’s most important medical institutions survived – just – and came to play a significant role in the treatment of the sick, once they had been adequately protected from the flames. As John Evelyn, once again, puts it:

“It was therefore now commanded to be practised, and my concern being particularly for the Hospital of St. Bartholomew near Smithfield, where I had many wounded and sick men, made me the more diligent to promote it; nor was my care for the Savoy less.”

This is the same St Bartholomew’s Hospital that still stands on the same site on the northern fringe of London’s Square Mile today. In 1666 it was the very edge of the area devastated and only escaped destruction itself as rows of houses and other buildings surrounding it were demolished to prevent the flames from spreading. Further west was the once great Hospital of the Savoy, on the site where the Savoy Hotel now stands on the Strand near Trafalgar Square (a tiny fragment of the hospital survives in the Queens Chapel of the Savoy, a private church or ‘royal peculiar’ of the monarch). Evelyn clearly fears the fire will reach there too and that the may wounded and sick in both places of safety will once more be plunged into danger.

In the event the conflagration never did reach as far west as the Savoy and so these two hospitals founded in mediaeval times almost certainly served as major places for treatment. As charities the hospitals would have provided cure either for free or at very low cost, as such they were uniquely placed to deal with this kind of emergency, just as they would be today.

How successful were 17th Century burn treatments? Do we have many accounts of their use?

Physicians and other medical professionals of the 17th century were essentially trying to achieve many of the same things when treating burns as today’s doctors are – to stop the burning process, ease or soothe the pain, protect the wound, promote healing and, by doing all of the above minimise damage to human tissue and prevent or reduce scarring.

Everyone of the treatments they used were deployed with one or more of these aims in mind. So, our exhibition is called ‘To fetch out the fire’ because these are the words that appear in recipes for medicines that are meant to take the sting out of burns.

The major difference between then and now is in the theories behind the medicines and how they worked. Today we rely on the concept that medicines have active ingredients or chemicals in them that produce the desired curative effect, in the 17th century medicine and chemistry – or alchemy as it was at the time – were only gradually starting to be seen together based on the controversial principles of Paracelsus (1493-1541), the philosopher, physician and father of toxicology.

Most mainstream medicine in this era was more like a type of theology, where new scholars poured over the texts of great writers from the past, the most famous being Hippocrates and Galen of ancient Greece and Rome, and refined their remedies or applied their ideas to new commonly found ingredients that seemed to fill in adequately for Classical substances that were more scarce in the cooler climes of Northern Europe.

As such alehoofe also known as gill-over-the-ground and catsfoot and today as ground ivy and, more properly, Glechoma hederacea had been recommended by Galen himself for inflammation of the eyes. It was therefore a small step for this common herb that was already pressed into service for everything from brewing to cheese making, kidney disease, indigestion and colds to be added to poultices applied to the inflammation caused by burns and scalds.

In the case of eggs and animal fats, which also feature very widely in the recipes, the suggestions for use are both antique and contemporary. The aim here seems to be to both protect the wound and prevent scarification. The eminent German surgeon Wilhelm Fabry whose seminal text of 1607 on the treatment of burns (which, incidentally, introduced the classification into first, second and third degree that we still use today) was known across Europe and translated into English and printed in London by the middle part of the century, cites Hippocrates:

“A dry and withered field produces twisted blackthorns, darnel and every kind of defective growth; but a good watered soil produces sound crops. In the same way the lack of natural warmth and moisture produces a nasty scar, as Hippocrates says “Biting cold hardens the skin, brings unendurable pain and blackens the ulcers”. To prevent this, from start to finish in the treatment softening applications must be used. Regarding treatments, the hardness of the scars must be soothed and softened with the greases of bears, hen and capon, oil of lilies and egg yolks…”

In essence, though bear’s grease and ewe’s tallow may sound utterly vile to us, they are playing a role somewhat similar to emollients and neutral moisturising creams, which some dermatologists still advocate during the healing process from minor burns. They soften and soothe the skin, prevent itching and hopefully reduce scarring.

A few remedies in use at the time of the Great Fire were more recent, pastes made of onions, which are also a regular favourite amongst the recipe books of the 17th century appear to have the great surgeon Ambroise Paré (1510-1590) as their source. An army doctor, who pioneered the treatment of gunshot wounds and introduced the first successful wound dressings, Paré appears to have come across the use of onions by chance whilst on service at the front, though it is possible he observed it in use by ‘traditional healers’. Convinced of its efficacy in easing pain and reducing the chance of blistering and scarring he recommended it in his widely admired and distributed texts.

It’s therefore possible to see that although many of the recipe books on display were originally written and owned by lay people, the remedies were largely the same as those prescribed by professionals – though the rationals may not have been the same. Given this, we can reasonably conclude that these remedies were the stand-by cures of the age, very widely used by doctors and public alike

This then begs the question as to whether any of them worked….

The first thing that must be said is that all the treatments were prepared in a world before there was any theory of asepsis or antiseptics, as such, whilst many of these remedies would undoubtedly achieve Soil Association Organic certification, many if not most would contain a host of rather dangerous bacteria that could infect the burns they were aiming to treat. This would have especially been the case with the deep, extensive and open wound burns caused by a major incident like the Great Fire of London.

It would also have been particularly true of those recipes – and there are many – that include dung from farm animals or birds droppings. All of which would have had no curative effect and most certainly could have given rise to serious infection.

Putting the question of germs to one side, in a world where there was little or no pain relief as we know it today, any of the more cooling herbs used at the time, such as alehoofe or chamomile may have provided some relief if used to wash the burn, likewise the dabbing of lavender oil to pulse points or near the wound ‘to calm the nerves’ may have helped to reduce the distress of the patient and bring them to a more stable state.

Applying grease, butter, eggs and oil to a fresh burn is undoubtedly a bad idea. Current medical advice is that these practices should be avoided as it prevents proper examination of the wound and may cause actual harm. However, it’s interesting to note that most responsible medical websites feel the need to repeat this warning even today: clearly the myths that surround the healing properties of these substances have persisted.

Slightly more complicated is the role of fats and greases in the dressing of partially healed burns. Many doctors in the present advocate the use of antibacterial ointments, others gels and creams containing aloe vera (a herbal remedy) and some simple moisturisers. Though produced under sterile conditions, most of these use petroleum or paraffin as base materials, so we have replaced animal with mineral ‘fat’ in the treatment of burns or, specifically, scars.

Interestingly, as with plague cures – many of which will also be on show, as the exhibition focuses on the Great Fire as the final in three terrible events to befall London: Civil War, plague, fire – burn cures from the time have actually made their way quite successfully into the beauty industry. Most face creams and moisturisers are based on fats, the fanciest pride themselves on containing proteins, just as eggs in the old cures did. Previously they fought the signs of scarring now of ageing. In the case of plague cures, or rather preventatives, galbanum, civet, oilbanum (frankincense) were all used to ward off plague and can now be found in Chanel 5 and 19, Guerlain’s Shalimar and Chamade and the majority of the world’s best selling and most sought after designer perfumes. Old cures never die, they simply turn up as something else.

Something you wouldn’t want to smell – onions – there’s no conclusive proof that juice of onions has any positive effect on minor burns; however, it is probably the most persistent of all the cures and is still widely used throughout the world in the catering industry, many restaurants actually keeping bottled juice on hand for this purpose.

Finally, the treatment of the kinds of burns that would likely have been sustained by the victims of the great fire would be treated mainly by advanced and specialised surgery today. Though the three vital actions if a wound is sustained and the patient is awaiting professional help remain the same: to stop the burning process, ease or soothe the pain and protect the wound.

Did the Great Fire leave any lasting impact on medicine?

The most important medical impact normally ascribed to the Great Fire is that it ended the Great Plague of London. In fact this is at best only partially true. In reality, the numbers dying from plague had fallen back from the calamitous figures of 12 months before when thousands were dying each week to the normal few cases every month that had been commonplace outside of major outbreaks ever since the plague arrived in Britain around 1350. That said, the Great Fire of London and the subsequent rebuilding of the city along more modern lines represent an end to plague in the capital in any significant way. London would never suffer another plague epidemic of the type it had suffered periodically for the past three centuries, though they continued to occur regularly on the continent.

Whilst the Great Plague left a significant medical legacy in the shape of a brilliant and detailed account of the treatment of the victims called Loimologia written by Dr Nathaniel Hodges, one of the two official physicians left in town, which not only influence clinical thinking on contagious diseases but also inspired authors such as Daniel Defoe when writing his A Journal of the Plague Year, it is difficult to identify a parallel influence exercised by the Great Fire.

Some historians have observed that recipe books compiled after the Great Fire contain a greater number and diversity of treatments for burns and that the works of the surgeon Wilhelm Fabry, who first categorised the injuries as first, second and third degree , were more widely read, but these changes, though they are significant represent an evolution rather than a revolution in treatment.

Charms play a role in 17th Century medicine too, such as bezoar stones and touch pieces, how were they used at the time of the Great Fire and who provided them?

Charms and amulets were hugely important in both medicine and life in the 17th century – an era of great religious and superstitious belief and conflict.

Bezoar stones, a 17th century example of which in its surviving filigree silver box forms part of the exhibition, are actually taken from the kidneys of antelopes bitten by serpents. These hard lumps were said by ‘quacks’ to ward off the plague. In the same way many people would have worn ‘pomanders’, pieces of jewellery specifically made to carry perfumed substances thought to prevent disease. Galbanum, frankincense and civet were all popular ingredients at the time and survive today in the form of some of the world’s most popular perfumes.

Gold ‘touch pieces’, are small coins marked with the image of the archangel Michael which were presented by the sovereign to the sick. A collection of those on show were given by King Charles I to over 100,000 of his sick subjects at healing ceremonies throughout his reign. In particular the disease scrofula, which is a swelling of the lymph nodes at the back of the neck caused by tuberculosis could be healed by the laying on of hands by the monarch at such a ceremony. So widespread was the belief that the disease came to be known as ‘The King’s Evil’ and The Common Book of Prayer actually included a specific church ceremony to accompany to ritual.

In the aftermath of the Great Fire, the city – having been afflicted by both plague and civil war in the recent past – came to belief that the blaze had been caused by divine retribution or the malicious influence of evil spirits. Such beliefs were entirely consistent with much medical though at the time with prayer and penance often being prescribed by doctors along side the more conventional treatments of the age. Given these beliefs, many of the inhabitants of London who didn’t subscribe to the commonly held opinion that the the fire was a ‘Popish’ or Catholic plot, began to pray for salvation, this was accompanied by the wearing of more ostentatious religious symbols by some and good luck charms and amulets by others – all in the hope of avoiding yet another calamity.

The Royal College of Physicians was hit directly by the Great Fire, do we have a good idea of what was lost and how the surviving artefacts came to be saved?

The Royal College of Physicians home at Amen Corner, just in the shadow of St Paul’s Cathedral was completely destroyed by the Great Fire of London.

The greatest loss to the College was the destruction of its fine library, gifted to it in part by Dr William Harvey, the brilliant doctor who was the first to describe the circulation of blood from the heart around the body. It is a tribute to the huge esteem in which Harvey was held by his contemporaries that amongst the tiny number of objects that were saved from the encroaching inferno by the staff and members of the College are both a magnificent portrait of the doctor and the pointing stick he used when giving his lectures.

Alongside a few important books, accounts and archives, the College did manage to save of some of its valuable silverware, in particular tiny silver bell. Dated 1636 it is thought to be the oldest hallmarked piece of British silver in existence and is still in use today when it is used to call for silence at the election of a new President of the Royal College of Physicians.

All of these surviving items will be on display in the exhibition, giving a glimpse of what was saved from the flames and hint at the treasures that were lost.

Out of the ashes of this devastation, the Royal College of Physicians was one of the first institutions to plan for its reconstruction after the Great Fire. Engaging the services of the city surveyor and great scientist Robert Hooke (amongst whose achievements is the identification of the flea that spread the Great Plague), the College commissioned a new and far grander building in the immediate area at Warwick Lane. The new building, which survived in the 19th century featured a splendid domed anatomy theatre, new library (with books supplied by a bequest from the Marquis of Dorchester, which remain in the College’s ownership to this day), grand courtyard and public rooms.

Completed from 1673 the new Royal College of Physicians was one of the first and most admired new buildings in the City following the Great Fire and came, along with new St Paul’s in whose shadow it now stood to serve as a symbol for a resurgent city.

‘To fetch out the fire: Reviving London, 1666’ runs at the museum of the Royal College of Physicians from 1 September to 16 December 2016. For more on the Great Fire of London, pick up the new issue of All About History, or to discover Charles II’s role in fighting the blaze, pick up the new issue of History of Royals.