In secret, riding through the air she comes,

Lured with the smell of infant blood, to dance

With Lapland witches, while the labouring moon

Eclipses at their charms.

-John Milton, Paradise Lost (1667)

Gunnhild, the infamous Viking queen that ruled over three nations, had many names: queen, sorceress, mother to a generation. Seen as a scourge to kings and kin alike, much of what we know of her must be pieced together from fragmented stories and the bile of her enemies. Many argue that she is a work of fiction, an amalgamation of various characters, all pulled together by later authors as a plot device in their political stories.

While her origins are shrouded in mystery, we do know that she was the 10th-century wife of Erik Bloodaxe, King of Norway, Orkney and Northumbria, with Gunnhild serving as his fierce queen. Most likely the daughter of Gorm the Old, King of Denmark, Gunnhild and Erik Bloodaxe were introduced to one another at a feast held by Gunnhild’s father. In this version, their union was intended to join two houses: the Norwegian Yngling family and the early Danish monarchy. Yet a much darker story is told in the Icelandic sagas, where she is instead the daughter of Ozur Toti from Hálogaland in northern Norway. In this version, Erik meets Gunnhild when he is given five warships by his father, King Harald Fairhair of Norway, and sets out on a long journey that ends in Finnmark – a remote northeasterly corner of Norway.

Here, they find a beautiful woman, held captive by two Finnar wizards. This is Gunnhild. She tells the visitors that while the men are the wisest sorcerers in Finnmark and they teach her their magic, they both want to marry her. She says that nothing can escape them, as they can track as well as dogs, and when they are angry the ground turns about, and all living things fall down dead. She beseeches the men to hide and lie in wait for the sorcerers, as they have killed all men that have been to the hut so far. On their return, Gunnhild soothes the wizards, promising that no one has visited while they were out, yet that night both men stayed awake, each jealously watching the other. Gunnhild called both to her bed, waiting until they slept soundly. She hurriedly tied them up, placing bags over their heads. She signalled to the hiding visitors, who jumped up and killed the wizards instantly, making for Erik’s ship the next day. Gunnhild sailed with Erik to Hálogaland to ask her father’s permission for their marriage, which he gave, and then they set sail together for the south.

While we, as modern readers, might have sympathy with Gunnhild being held by two men against her will, at the time these stories were written down as histories of the people, attitudes were very different. This story would help readers to believe that Gunnhild was a sorceress and murderer, certainly not a suitable wife for a king. We can see the seeds of doubt being planted in the minds of the people that King Erik’s later reign of tyranny and bloodshed can be blamed on Gunnhild, and her reputation is only compounded as her story progresses, when she is painted as the archenemy of the legendary hero, Egil Skallagrímsson – the protagonist of Egil’s Saga, the earliest copy of which dates from the 12th century.

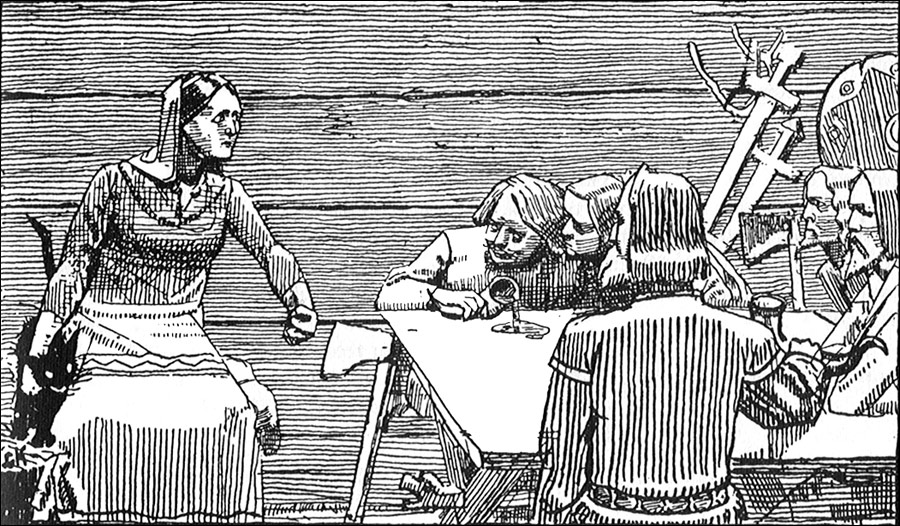

The pair have a long history in the sagas, coming together time after time, in a battle of wits steeped in death and treachery. Their story begins at a feast to the guardian spirits, where Egil insulted his hosts, Gunnhild and Erik, by boasting that their beer could not quench his thirst, a dire insult to their hospitality. Gunnhild retaliated by mixing together a poison to kill Egil, yet, realising what was happening, Egil – who was said to wield his own magic – made a spell against them by cutting runes into the drinking horn and smearing his blood on to it, before killing their overlooker and making his escape. Egil evaded Gunnhild’s vengeance often and she was infuriated at his insult and trickery.

It’s in the middle of the story that Gunnhild’s reputation went from scheming and unruly to ruthless and politically dangerous. When Harald Fairhair was 80 years old, he turned over rule of the kingdom to Erik, giving him sole control over all of his lands, and naming Gunnhild’s own son, Harald Greycloak, as the next heir. Erik’s brothers were enraged and a savage feud ensued, ending in bloodshed on all sides, with Erik notoriously killing four of them. Many of the jarls blamed Gunnhild’s sinister machinations for his actions in her relentless quest for power. Mutterings of how Queen Gunnhild hired a witch to brew a poison to kill Hálfdan the Black at a banquet could not be quelled, and with this mistrust they chose another of the brothers, Sigröth, as their ruler.

Erik and Gunnhild’s control was diminishing, and something had to be done. In the time after Harald Fairhair’s death, Erik went to war against his brothers, raising a great army and winning victory at Túnsberg, and killing two of his brothers Óláf and Sigröth to secure his reign. While still revelling from their victory, a tragic course of events were set in motion when Rögnvald, Gunnhild’s son, was killed by Egil during a raid. As a further blow to the royal couple, Egil set a curse upon them so macabre that the details are recorded clearly in the sagas.

First of all, the sorcerer Egil set himself at the top of a headland, facing the raging seas below. Next, he took a hazel staff and cut runes into the shaft in a manner reserved only for the direst of situations. He fixed the pole in the ground, securing the severed head of a horse on top, pointing it towards the waves. Swiftly, he turned the head to face where Gunnhild and Erik lay, and screamed out a curse to the sky, that the guardian spirits of the land should drive them out of Norway as punishment for Gunnhild’s workings against him. Legend tells that this curse took hold of Erik and Gunnhild, with the fates now leading them down a spiralling path of disaster that would ultimately lead to Erik’s death.

A year after King Harald Fairhair died, his son Håkon – later Håkon the Good – heard news of Erik’s tyranny in Norway, and set sail from England to challenge him. It was a turbulent voyage across fierce seas, and soon a message reached Norway that Håkon was lost at sea. Yet Gunnhild stood firm, resolutely telling Erik that Håkon was alive. Gunnhild was viewed with suspicion and accused of sorcery, for she could not have known of Håkon’s fate, other than through witchcraft. Indeed, Gunnhild’s words were true, for Håkon soon returned. By the summer months, the Norway’s jarls had risen up to make Håkon their king. Gunnhild and Erik could do nothing, and they fled to Orkney with their children, where Erik was accepted as king.

Here, accounts of events become murky. Some say that Erik and Gunnhild were offered the seat of Northumbria by King Æthelstan, ruler of the bulk of England not under Viking dominance. This seems unlikely, as he was the foster father of Håkon and had sent the prince home to reclaim his throne. Other accounts say Wulstan, Bishop of York, sent the invite, yet others claim that when the royal couple reached English shores Erik died and left Gunnhild to her fate. According to the Icelandic sagas, after harrying along the north-eastern coast and wreaking havoc along their path, Gunnhild and Erik made their home in York in 952 and the family was baptised into Christianity.

Gunnhild’s fury had not abated with their journey; she still blamed Egil for their fall. She set to work a spell against him, that he should find no peace in Iceland until she had seen him. A year later Egil set sail for England to see King Æthelstan. Gunnhild’s curse wrapped its fingers around Egil’s fate: he was shipwrecked, and the storm brought him directly to the shores of Gunnhild’s lands in Northumbria. Realising that he could not escape, Egil went to Erik and Gunnhild, imploring them to be reconciled. Gunnhild’s anger was not to be turned. Erik decreed that Egil should be killed the next morning. Egil did not spend his last night idly; instead, he worked until daybreak to compose a great poem in tribute to King Erik, in hope that it might win him his life. It did.

Gunnhild and Erik lived on in Northumbria until around 954, when their seat was threatened as a wave of political upheaval fell over England. Erik chose to leave Northumbria, becoming a scourge of terror across the country, before he was finally stopped by the English at the Battle of Stainmore with his death closing the book on Viking rule in the north of the country.

When this news reached Gunnhild, life as she knew it ended: the people of England blamed her for the bloodshed that Erik had rained on them. She gathered her wits, drawing all their possessions and wealth together, before fleeing, once more, to Orkney with all the men and ships they could muster. Thorfinn Skullcleaver, Earl of Orkney, made them welcome, and Gunnhild and her sons took power there for a while, until they heard news from Harald Bluetooth, Gunnhild’s brother and King of Denmark, that he was displeased with King Håkon, concluding that they might at last be able to return home to Norway. She married her daughter Ragnhildr to Thorfinn to form an alliance in Orkney and took refuge with Harald Bluetooth, where he gave them lands to support them.

Gunnhild stayed in Denmark for many years while her sons tried to win back their father’s lands from King Håkon. It seemed that Egil’s curse against them was finally losing power when they mustered a considerable army against him and won a great victory in the Battle of Fitjar in 961. Their enemy, Håkon, was mortally wounded with what was said to be an arrow to the shoulder and there were once more whisperings that it was her dark magic that had won them both the day and the Kingdom of Norway. Gunnhild revelled in her position when her son, Harald Greycloak, came into power, and she had much sway in the government of the country; it was at this point she was given the title Mother of Kings.

Like in other areas of her life, Gunnhild wielded her sexual prowess as a weapon. After Erik’s death, Gunnhild took a younger lover and made no secret of it. Hrut, a young Icelander, caught Gunnhild’s eye when he arrived from the west by boat, armed with the task of pursuing a man named Soti who had taken his inheritance. Gunnhild unabashedly offered her help with his plight, suggesting that he and his friend Ozur stay with her over the winter. Being patroned by a powerful queen like Gunnhild changed the course of Hrut’s life forever. At first, he had more than luck on his side, with Gunnhild bestowing lavish gifts and refusing to believe that any man could better him in cleverness. She even went so far as to encourage her son, King Harald Greycloak, to take him on as a bodyguard.

While we see other women in the sagas shrinking away from their men’s rough embraces, Gunnhild breaks convention by flaunting her affair with Hrut, kissing and embracing him in public like a married couple would. She went so far as to spend two whole weeks with him, both sleeping each night locked together in her bedchamber. While she didn’t mind engaging in her affair openly, Njáls Saga does show her threatening the guards that they if they spoke of the relationship she would have them put to death. Most scandalous of all in the eyes of her contemporaries was the age difference between them: Gunnhild was a generation older than Hrut, yet this didn’t bother either of them. That was until Hrut set out to pursue Soti to Denmark, with the gift of two longboats from Gunnhild. On his return, Gunnhild noticed that Hrut had grown quieter, and she suspected something was amiss. She questioned him about having found another lover while away. Hrut protested, and denied every accusation, yet soon requested leave from King Harald Greycloak that he should return Iceland. Before he left Gunnhild gave him a gift: a fine gold bangle, which she placed on his arm with her own hands. She leaned in to whisper her parting words: a spell. She cursed Hrut that he would have no pleasure with the woman he secretly intended to marry in Iceland, as he had lied to her. Hrut left her with a smile, but it was a smile that would not last.

On his marriage to Unn, he found that he was not impotent, but instead hyper-potent. The sagas go to great lengths to labour the point with the warrior kennings used for Hrut: spear-sharpener and bow-bender are just two of these, and the irony cannot escape us that the name ‘Hrut’ itself means ram. Unn finally confided in her father that “there’s a spell on his spindle”. Like many fathers would, he advised that she should fain illness, while taking other men to her bed. Only then should she proclaim a divorce. On Hrut’s return, he found his wife gone. Gunnhild had won her revenge; her spell against him had worked. Hrut learned that Gunnhild was a powerful ally, but an even more powerful enemy.

Gunnhild’s tempestuous rule ended when her own brother, Harald Bluetooth, turned against them in 971, scheming with the noblemen of Norway to kill Harald Greycloak, her son. Now an elderly woman, Gunnhild fled to her daughter in Orkney with her family once more, where they ruled until the men under her influence were dead.

If ending as a wife and mother who outlived both her husband and her sons was not cruel fate enough, six years later in 977, Harald Bluetooth dealt her one final blow: he decreed that, for her wickedness, she should be thrown into a bog and drowned. Gunnhild was killed at the hands of her own kin.

Dee Dee Chainey is one of the founders of Folklore Thursday. For more dark deeds from Early Medieval rulers, subscribe to History of Royals and get every issue delivered straight to your door.

Sources:

- C Downham, Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland. Dunedin 2007

- J Jochens, Women in Old Norse Society. Cornell University Press 1995

- B Scudder (translator) & S. Oskarsdottir (introduction), Egil’s Saga. Penguin 2005

- S Sturluson, Heimskringla: A History of the Kings of Norway (translated by L. M. Hollander). University of Texas Press 2009