Almost everyone knows 1066. But how many people know that England was conquered 50 years earlier, in 1016?

The invader then was Cnut – the king now known for vainly trying to turn back the tide. His victory marked the culmination of a century and a half of Viking attacks on England. However, having conquered the country, the Danes left England pretty much as it was. Their main innovation was the introduction of a new class of warrior – the housecarl. When the Normans landed in 1066, the spine of the army that faced William was composed of King Harold’s own housecarls. In one of history’s great ironies, this meant one set of Viking-derived warriors faced another: the knights of Normandy. The Normans were descendants of Vikings too, and so the battle for England had become a Viking affair.

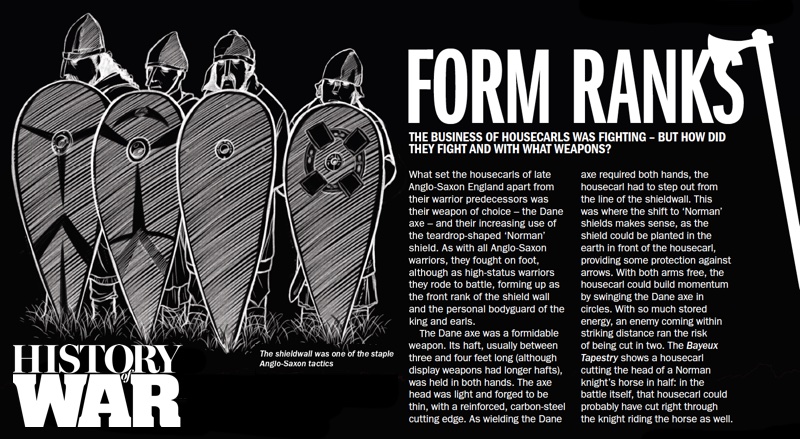

Leading the battle on the English side, Harold’s housecarls stood proud atop Senlac Hill, their shields locked in the warrior wall erected to prevent William’s march into England. As the Norman knights charged up the hill, occasionally a brave man would step out of line, wedge his shield into the earth and swing his great two-handed Dane axe. Such was its momentum that it might cut horse and mail-clad rider in two.

These soldiers had already defeated the army of Harald Hardrada of Norway, the most feared Viking king of the time. Although they’d not even had three weeks to recover from the Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25 September, the confidence born of that victory must have sustained Harold and his men on the march south and as they formed their shieldwall. The housecarls were the elite troops of their age. Now, tested again, they would prove it.

Only, as we now know, they failed this final test. Many had fallen at Stamford Bridge, but even with their numbers depleted, they withstood William’s men for a long, bloody day at Hastings – when most early-Medieval battles ended within an hour. Even when King Harold fell, most of his housecarls fought to the death.

To explain the valour and combat strength of these troops, scholars examined the records of the time to find what set them apart from the norm. The majority of Harold’s army was composed of the fyrd, the muster of free men called upon to take up arms in service of their king. These were farmers and artisans, armed with spears, wearing leather jerkins and carrying shields. They were strong and brave men – you couldn’t take your place in a shieldwall without bravery – but not elite soldiers. The housecarls were different.

The word, derived from Old Norse and meaning house and man or servant, first appears in English records after Cnut’s victory of 1016. Contemporary records are sketchy. They were members of noble households as warriors, and on one occasion tax collectors. However, to explain how such warriors could defeat Harald and come within an hour of dusk in holding back William, scholars looked to other sources. In particular they turned to the Lex Castrensis Sive Curie, contained in the late-12th-century works by the first Danish historians, Sven Aggeson and Saxo Grammaticus.

What wonderful material they found there. According to Aggeson and Grammaticus, Cnut had created a code of rules to regulate his warriors, called Witherlogh in Danish. Having won the throne of England, the king paid off the majority of his army with Danegeld raised from his new subjects. One of the reasons so many people were so keen to invade England was the efficiency of its tax gatherers: Cnut raised the astonishing sum of 30,800 kilograms of silver to pay his men, and this after the English had spent the previous two decades paying increasingly large sums of Danegeld.

However, Cnut kept the crews of 40 ships to act as a standing army, paid for by a regular tax. He then promulgated a decree that any man wishing to join this warrior brotherhood must show their wealth and worth with gilded axe heads and sword hilts.

In the spirit of getting in with the new boss, as many Angles and Saxons as Danes applied to join Cnut’s house men. Finding himself now king of a sea-spanning empire that encompassed England, Denmark, Norway and some of Sweden, Cnut had to find some way of knitting together his household troops. He did so by a law code that required the men to sit in order of precedence in his hall, with the noblest and bravest nearest the king. Infractions were punished by being sent to the end of the table, where the other housecarls might pelt the miscreant with bones and scraps.

A housecarl who offended had to be tried before the whole body of men. Even Cnut was not above the rules: when he killed a housecarl in anger, he was tried before the assembly of men. Although they acquitted him, Cnut fined himself for the crime.

Generally, the punishment for killing another housecarl was exile or death, while treason was, naturally, punishable by death and confiscation of property. In return for their service, Cnut provided his housecarls with board, lodging, entertainment and a monthly salary. Housecarls were not bound to service, but according to the Lex Castrensis, they could only leave their post on one day during the year: New Year’s Eve. This was also the day when the king gave gifts, thus making it less likely any man would leave his service.

So, according to the Lex Castrensis, Cnut had a standing army whose wages were paid for by regular taxation, and who were bound by a particular and unique law code. This was an extraordinary accretion of royal power and one unparalleled elsewhere in Europe.

But was it true? Remember, the reconstruction of the role and function of housecarls in English society between 1016 and 1066 was based almost completely on documents written in a different country in the late 12th century, more than 100 years, or at least four generations, later.

Scholars believed that these accounts were accurate because they matched two incidents from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which apparently described housecarls tried before their own assembly and sentenced according to the law code in the Lex Castrensis. The whole argument for reading a late-12th-century document back to the early-11th century rests upon these two entries in the Chronicle – and the correct translation of just three words. But now it seems those words – here, niðing and stefn – were not used in the precise sense demanded by this argument but had become generalised in the usage of the time.

The Lex Castrensis was composed in 12th-century Denmark as the king there was attempting to increase his control on contemporary housecarls, who really were a political and military elite. How much easier to do so if it could be shown that their law code went back to Cnut the Great himself. Therefore, we can answer cui bono: who would benefit from this historical interpolation?

Recent scholarship has debunked the old idea of the housecarls as a discrete, standing army, bound by its own set of laws and acting as the king’s troubleshooters. So, who were the men that fought alongside Harold through the autumn of 1066?

Well, one thing is for sure: they had axes. The great two-handed Dane axes were their characteristic weapon and something that set them apart from the thegns of the pre-Cnut era. But, in most other ways, they were indistinguishable from the thegns who had long served the Anglo-Saxon kings.

Thegns had started out as warriors, members of the warbands that the first generations of Anglo-Saxon kings gathered around them, held to service by the gift-giving of the king. As time passed, the duties of the thegn broadened. As reward for service, a thegn would be gifted land, where he acted as the king’s representative, but this land returned to the king upon the thegn’s death. However, with the rise of monasteries, this reversion of land became untenable: institutions needed to own their land in perpetuity so that they could adequately plan for the future. So, from Offa onwards, the Anglo-Saxon kings developed the idea of bookland, where ownership of land was inscribed in deeds into books of record.

The idea, once developed, swiftly proved irresistible to the Anglo-Saxon warrior aristocracy, as it meant that a thegn could pass on land to his children, and hold that land within his family through the generations.

With this development, the qualification for the rank of thegn shifted towards property, so that by the time of Æthelred, a ceorl could ascend to the rank of thegn if he could assemble sufficient property, including five hides of land, a church, a kitchen and bell house, as well as duties in the king’s hall. Even a merchant could become a thegn if he were able to fund three trading trips abroad. This was reflected in the language. Old English ‘rice’ (‘rich’ in modern English), which before had meant a powerful man, came to mean a wealthy man.

With increasing access to the rank of thegn, there grew increasing divisions within it, with those attending upon the king most highly ranked. Documents of the time sometimes refer to the same man as ‘cynges huskarl’ and ‘minister regis’. The latter term (‘minister to the king’) indicates that housecarls, and particularly those attached to the king’s household, had other duties apart from warfare – just as well, really, since even a society as chronically violent as 11th-century England was not permanently fighting.

One of the most vivid examples we have of the further duties of the housecarl comes from the brief reign of Harthacnut, Cnut’s son. Not taking any chances on the supporters of the previous king, his late half brother, Harold Harefoot, Harthacnut had arrived on English shores with a fleet of 62 ships. Although he received the throne without demur, Harthacnut still had to pay off his men and, like his father, he did so by taxing the people he was going to reign over. Among the tax gatherers Harthacnut sent around the kingdom were his own housecarls, two of which were sent to Worcester where they proceeded to annoy the local populace so much that they dispatched the tax gatherers.

An enraged Harthacnut ordered the rest of his housecarls to Worcester with the command to ravage and burn the city, and to kill all the men. Luckily for the people of Worcester, they received warning and almost all fled with their lives. The housecarls looted for five days and then burned the city down, which was enough to assuage Harthacnut’s anger.

As members of royal or noble households, housecarls were paid a wage, but they were not mercenaries. A mercenary is a soldier who fights for whoever will pay the price. In distinction, a housecarl served his lord, for which service he received a wage. There was no contradiction between receiving a wage and loyalty unto death.

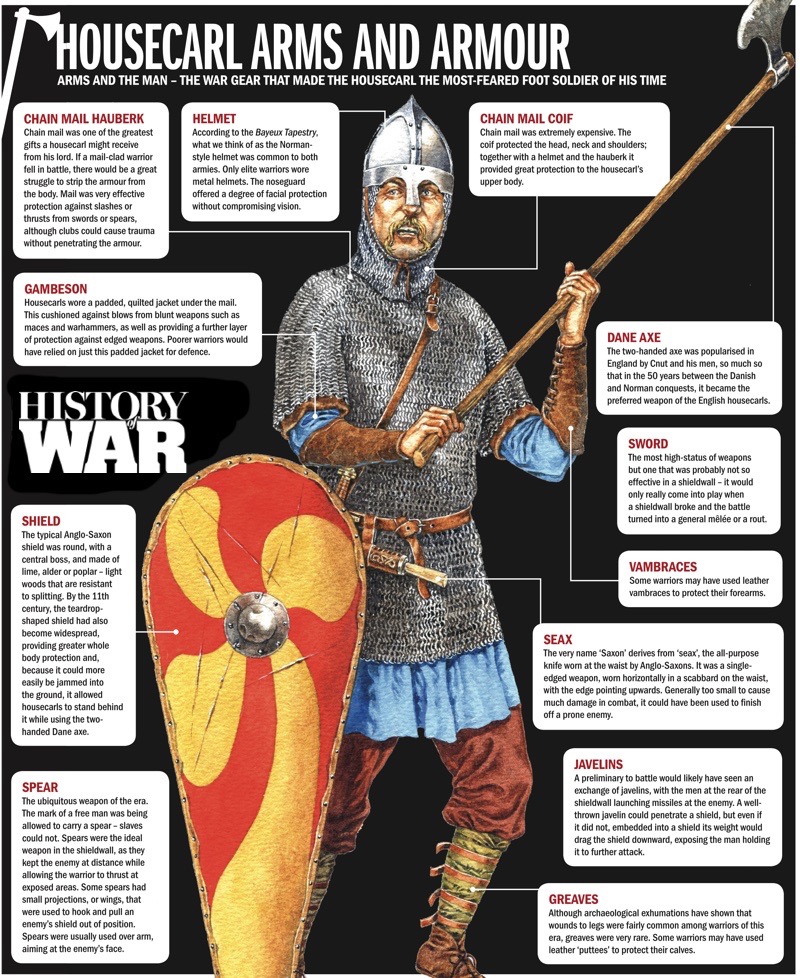

This wage, and the gifts given by their lord, enabled those housecarls who were not landholders to pay for their war gear. Relatively few housecarls seem to have held land – the main source of wealth at the time – so they must have depended on payment, gift giving and trophy taking after battles or contests to build and maintain their war gear. Not surprisingly, housecarls lavished money upon their equipment. Particularly for those employed in the household of the king or his great earls, the more resplendent the war gear, the higher the status of the wearer. When it came to the chaos and blood of the shieldwall, good war gear became, quite literally, a matter of life and death.

We can say that recent scholarship indicates that the old idea of housecarls as a discrete body of men, bound by their own law code and acting as the king’s standing army is false. After Cnut’s conquest, the terms housecarl and thegn seem to have been used interchangeably, with the only significant difference being that housecarls were originally more likely to be Danish. As high-status warriors, they were still called upon to serve king and lord and, by virtue of their training and weapons, they did form an elite group of infantry. As the men of Harold’s household stood on Senlac Ridge, fingering the shafts of their Dane axes, they must have been confident in their ability to see off this new pretender to the crown of England.

We know they failed, but of those that survived, many went into exile and, taking their martial skills with them, migrated east to the court of the last Romans, the Emperors of Byzantium. In the aftermath of Hastings, English housecarls went on to form the backbone of the emperor’s Varangian Guard, which became known as an Anglo-Saxon force. From the ends of the earth, the last housecarls finished their service at the centre of the world, serving the last emperors – a fitting swan song.

Edoardo Albert is the author In Search of Alfred the Great: the King, the Grave, the Legend (with Katie Tucker) and Northumbria: The Lost Kingdom (with Paul Gething). His most recent book, the third part of his Northumbrian Thrones trilogy, Oswiu: King of Kings, is available now. For more on early Medieval warfare, subscribe to History of War for as little as £26.