From the 27th-30th December 2017, the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds will be taking a trip back to the 17th century for its English Civil War-themed ‘Christmas is Cancelled’ event.

Caught in the turmoil after the bloody English Civil War, visitors must choose whether to join the Royalist Christmas insurgents determined to celebrate the season with music, decoration and delicious food, or the Parliamentarian ‘riot police’, equally determined to prevent any sign of idolatrous behaviour.

Throughout the event the two camps will be stationed around the museum delivering dramatic performances and engaging opportunities to delve into the period. Among the characters will be soldiers from New Model Army as well as Royalists in support of the return of monarchy.

Christmas was effectively banned in Britain by a 1644 Act of Parliament, with the Long Parliament of 1647 passing an ordinance which officially abolished the feast of Christmas making its celebration punishable. The ban remained in place until the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. We spoke to curator Keith Dowen to understand the context behind this exciting new event.

What were the dominant Christmas traditions that particularly provoked the ire of Parliamentarians?

Before the Civil Wars (in fact since the 16th century) many Puritans had been troubled by what they saw as the sinful boisterous nature of Christmas with its extravagance, waste and immorality. In their minds it also had too strong an association with the old Catholic faith of which Christmas had been an important part of the liturgical calendar. Another very important complaint was that they saw the festivities as being pagan, having no basis in the Bible.

How was the ban on the feast of Christmas actually enforced?

Puritans wanted Christmas Day to be a day of fasting and humility, but otherwise a normal working day – not a Feast or Holy day as it had been in the past. Indeed, MPs sat in Parliament on Christmas Day 1643 as though it was any other day of the year. Such measures were not uniformly popular, even in Parliamentarian-dominated London. That same Christmas, for example, some angry Londoners keen to follow the old traditions of Christmas, attacked shops that opened.

In January 1645 Parliament a New Directory of Public Worship which stated that there were to be no Holy Days apart from Sunday. In June 1647 Parliament passed an ordinance which confirmed the abolition of Christmas, Easter and Whitsun and during the 1650s (during the Commonwealth) legislation put in place penalties on those found attending special Christmas church services, or for closing their businesses for the day. In 1657 the Council of State urged the mayor of London to clamp down on celebrations.

Enforcement of the legislation was another matter, whilst some church ministers were arrested in 1647 for preaching Christmas sermons, many people continued to celebrate the season despite Parliament’s official position. The fact that Parliament had to keep issuing proclamations against Christmas throughout the 1650s shows that, until later on in the decade, many people ignored the prohibition.

Conversely, how important was the idea of celebrating Christmas as an act of defiance? Who was most likely to be keeping the tradition alive?

Celebrating Christmas had been a long established tradition and gave people a chance to ‘let of steam’ and enjoy more of the pleasures of life. It was also a much valued holiday away from the hardships of everyday work. As such many people from all walks of life continued to celebrate it.Continuing with the celebrations was at times certainly an act of defiance, even by Parliament’s supporters, as many saw the government interfering in areas of life it had no business to.

For the Royalists, they saw the victorious Parliamentarians as ‘killing off’ Christmas. One Royalist ballad of 1645 complained that “Christmas was killed at Naseby fight” – a reference to a major Royalist defeat by Parliamentary forces at the battle of Naseby on 14 June 1645. Royalist clergymen also engaged in writing pamphlets defending the celebration of Christmas and the importance of passing on these traditions to the young.

At Christmas in 1647 in Canterbury the town crier had proclaimed the committee’s commitment to the suppression of Christmas. In response a large crowd gathered to demand the usual traditions be observed. Eventually a riot broke out, forcing the mayor and several magistrates and clergymen out of the town. A few months later Kent rose in revolt in the name of King Charles I. Christmas also remained particularly popular among England’s community of Catholics or ‘Recusants’, who regarded the celebration of Christmas and devotion to the Virgin Mary as essential tenets of the faith.

What form would a ‘rebel Christmas’ take?

Christmas traditions really stayed the same from the Middle Ages and throughout the Civil Wars. In many ways, we still observe them today. Despite the official ban many still decorated their homes and doorways with holly, bay, ivy and rosemary. People gave gifts especially to the young and the poor, attended church services, feasted and drank copious amounts of alcohol – including ‘wassailing’ which involved going from door to door singing and drinking from a communal wassail bowl whilst wishing people good health (waes thu hael).

Carol singing was an important part of Christmas and some MPs complained that their neighbour’s preparations for Christmas had disturbed their sleep. Mince pies (made with real minced beef) were eaten, as was plum pudding. Morris dancing was another feature of Christmas, as was gambling. As I mentioned previously, Catholics were particularly attached to Christmas and were known for their great Christmas festivities. Some Catholics may have attended illegal Catholic masses in the homes of wealthy Catholic gentry and nobility – one aspect of the Christmas tradition they would have had to have kept secret from the authorities.

An early version of Father Christmas seems to make his debut in art around this time, was he already a character in the popular imagination or is he merely a personification of the season conjured up for satire?

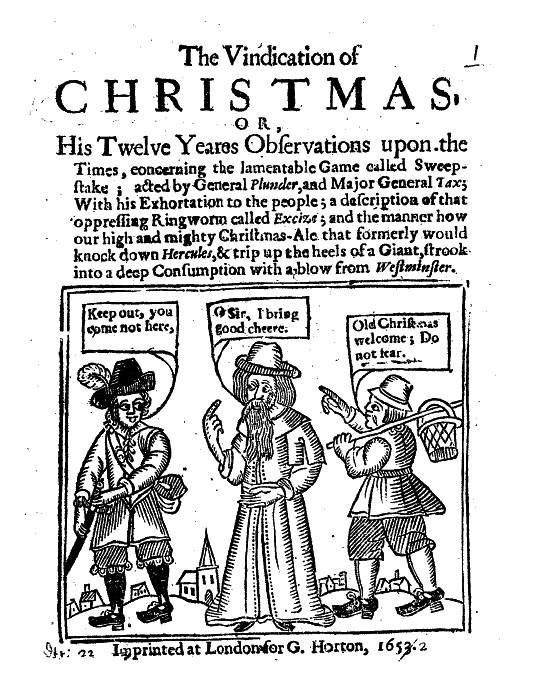

‘Sir Christemas’ had appeared in song in the 15th century, but certainly in the 17th century the personification of Old Father Christmas served as a means of defending the season from Puritans, after all people can generally relate much better to and empathise more towards a person than an idea. In the 1652 ‘Vindication of Christmas’ published by the Royalist John Taylor, a bearded ‘Father Christmas’ defends himself as only bringing “good cheere” (notably one Englishman is clearly happy to welcome him).

In 1658 Josiah King published ‘The Examination and Tryall of Old Father Christmas’ in which ‘Christmas’ is depicted as a white-haired old man on trial for his life – certainly a deliberately sympathetic image, and naturally ‘the jury’ acquits him. I’m not sure when Christmas is first depicted as an old man, but certainly by the late 16th century.

Find out more about ‘Christmas is Cancelled’ at the Royal Armouries on their website. For more delightful curios from history, subscribe to All About History for as little as £26.