The Hundred Years’ War has been defined by the historical figures that emerged out of the chaos that engulfed France between 1337-1453. Most of them were English royalty and included Edward III, the Black Prince and Henry V – men who led endless campaigns to pursue what they considered to be their rightful claim to the French throne. Between them they won great victories that became famous, including the battles of Crécy, Poitiers and Agincourt.

It is also often presumed that an effective French resistance only emerged in the late 1420s under the unlikely leadership of the illiterate peasant girl Joan of Arc. This is a grave misinterpretation of events and far from being a continuous conflict, the period was punctuated by cycles of both war and peace and victory did not always belong to the English. Before the dramatic conquests of Henry V, there had been a remarkably successful period of French resurgence where the majority of Edward III’s territorial gains were overturned. The man most responsible for this reversal was a Breton knight of obscure origins but near infinite courage: Bertrand du Guesclin.

A Breton Squire

Nicknamed ‘The Black Dog of Brocéliande’ or ‘The Eagle of Brittany’, du Guesclin was arguably the most renowned captain who fought for France during the Hundred Years’ War, but his early life gave little indication of his future greatness.

Born around 1320 near Dinan in Brittany, du Guesclin was the eldest of ten children and his family were a minor branch of the Breton nobility. As his father was only a ‘seigneur’ (lord of the manor), du Guesclin was a mere squire and he grew up to become famously ugly and of small stature. One story claims that his beautiful mother rejected him at first sight.

Like many young men of his status, du Guesclin entered local military service in the 1340s as a mercenary captain in the service of Charles of Blois before entering the service of King John II of France in 1351. After succeeding his father as the seigneur of Broons du Guesclin, he was then knighted by the marshal of France in 1354. From that moment, he spent the rest of his life serving the kingdom.

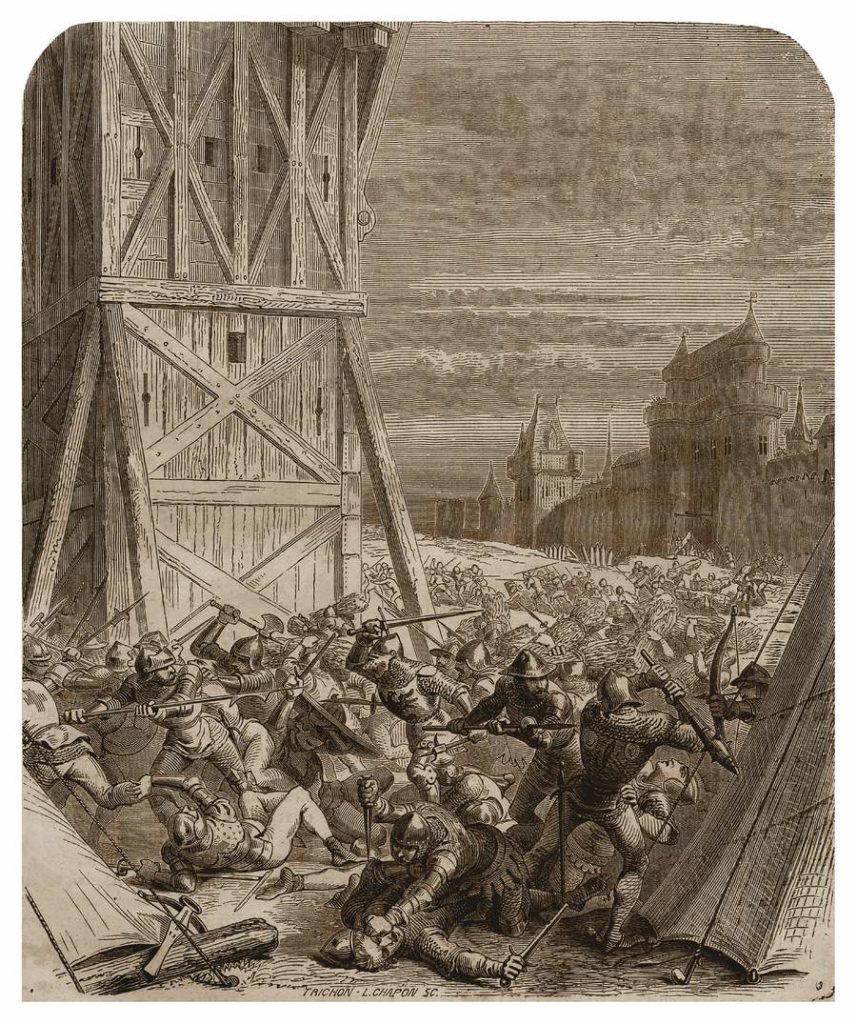

Du Guesclin’s first prominent action came during the Siege of Rennes between 1356-57 where he took a leading role defending the town from the besieging army of Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster. This was notable in the wake of almost unbroken English successes, particularly after the crushing Battle of Poitiers the previous year. One man who recognised the emerging talent of du Guesclin was the Dauphin Charles, who granted him a life pension of 200 livres and named him the captain of Pontorson, which was a strategic fortress on the Breton-Norman frontier.

Following this initial achievement, du Guesclin suffered a series of setbacks when he was captured by the English twice between 1359-60. In a telling sign of how low French fortunes had sunk, du Guesclin paid his ransoms by borrowing money from the duke of Orléans, who was himself a prisoner in the Tower of London.

By the 1360s, France was crippled. With John II held prisoner by Edward III after Poitiers, the English demanded a huge ransom of 3 million crowns as part of the Treaty of Brétigny. Under its terms, the English retained Aquitaine and acquired new territories that comprised a quarter of France in full sovereignty. Nevertheless, upon John’s death in 1364, the kingdom gained a new monarch who would largely reverse the humiliations of Brétigny.

Cocherel and Auray

Charles V’s succession to the throne was difficult. Even before his father’s death, he had to contend with the English and the king of Navarre, known as ‘Charles the Bad’. This Pyrenean monarch held extensive lands in Normandy, which enabled him to blockade Paris. When he was deprived of what he saw as his rightful claim to the duchy of Burgundy, Charles the Bad raised two armies and passed through Aquitaine en route to Normandy with the Black Prince’s permission. His Anglo-Gascon forces were commanded by a notable soldier called Jean de Grailly, Captal de Buch but the Dauphin Charles already had 1,000 ‘routier’ mercenaries in Normandy.

This small force was ostensibly commanded by the count of Auxerre, but it was actually led by du Guesclin who followed Charles’s orders to attack Navarrese fortresses. By the time the captal arrived in Normandy, most of the strongholds had surrendered and du Guesclin blocked his eastern path in a defensive line before the River Eure. The captal’s army numbered around 6,000, in comparison to the 1,500-3,000 that du Guesclin had scraped together, but neither commander wanted to make the first move. The opposing armies faced each other in a two-day standoff near Houlbec-Cocherel.

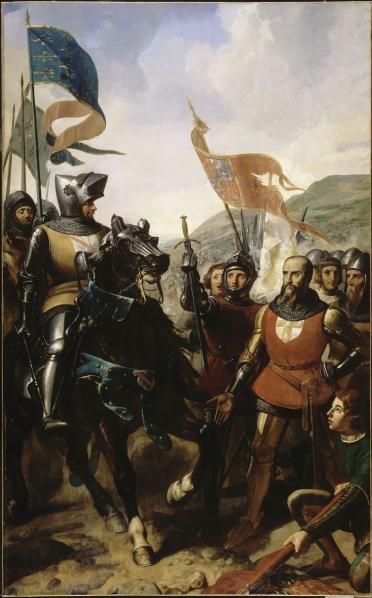

On 16 May 1364, du Guesclin attempted to withdraw when his food supplies ran low but the captal was determined to prevent his escape and sent in his cavalry to outflank the French and block their access to the Eure bridge. The Battle of Cocherel began and it was strongly contested. The Navarrese army initially had the upper hand, thanks to their superior numbers, but the French managed to outflank them. Du Guesclin then forced a retreat when he deployed his Breton reserves. Surprised by this reversal of fortune, the captal’s forces fled and he was personally surrounded with 50 of his men and fought in a bloody last stand. The captal was wounded and captured while the majority of his men were killed.

It was a dramatic victory for du Guesclin, and his success bode well for the future as the battle had taken place three days before Charles V’s coronation. Charles the Bad’s streak was broken and Navarre never seriously threatened France again.

One king may have been defeated but Charles V still had many problems. Although the war with England was officially over, it nevertheless continued in du Guesclin’s home duchy of Brittany. Over 20 years, two factions under the houses of Blois and Montfort fought for the ducal title and the English ruthlessly exploited the destabilising situation. Charles supported the Blois faction and du Guesclin was sent to Brittany in September 1364 to aid Duke Charles of Blois in his claim.

The two armies of Blois and John of Montfort met at Auray on 29 September and the Montfortian army was conspicuous due to its extensive use of English soldiers and commanders. Out of the five commanders fighting against du Guesclin, three were English and the famous longbowmen were a conspicuous presence. Against this military machine, du Guesclin’s chances were unfavourable and although the armies were evenly matched at between 3,500-4,000 men, the English-dominated Montfortians prevailed.

The combat was particularly bloody as both sides wanted the encounter to end the Breton war and no quarter was given. The most significant casualty was Charles of Blois, who was killed, and du Guesclin was forced to surrender to the English commander, Sir John Chandos, but only after he had broken all of his weapons. John of Montfort was now recognised by Charles V as Duke John IV but despite du Guesclin’s defeat, Charles ransomed him and he was soon back in royal service. The reason for this rehabilitation became clear as the king needed du Guesclin to deal with perhaps the most serious problem in his kingdom besides the English: the merciless ‘routiers’.

‘Routiers’ and Spain

After the Treaty of Brétigny, many soldiers were left unemployed, particularly those who had served under Edward III or the Black Prince. While on campaign, these men had grown accustomed to living off the land and they were reluctant to return home to a life of poverty or serfdom. As a result, large groups of mercenaries rampaged at will across France without any sufficient force to counter them. To protect their interests, the mercenaries formed into bands known as ‘Free Companies’ or ‘routes’ and they became known as ‘routiers’. One historical chronicler wrote that these groups, “…wasted all the country without cause and robbed, without sparing, all that ever they could get. They violated and defiled women without pity and slewed men, women and children without mercy.”

The routiers were particularly dangerous because of their professionalism. Not only were they former soldiers, but each company had a command structure with a staff to collect and distribute loot and some even had their own uniforms. Their nationalities varied and included Bretons, Spaniards and Germans but the majority were either Gascon or English with the latter being the most dominant group. Tellingly, the French described all routiers as ‘English’ and many of the most successful captains were enemies of du Guesclin, such as Sir Robert Knolles and Sir Hugh Calveley. Knolles became so notorious for burning towns that charred gables were nicknamed ‘Knolles’s Mitres’. Elsewhere, Sir John Harleston’s routiers once had a party where they drank from 100 chalices stolen from Champagne churches.

This organised chaos was a widespread problem and Charles V had neither the troops nor money to deal with them. However, he sent du Guesclin to rid Anjou of the routiers. This was a shrewd move as du Guesclin was a former mercenary himself, but he managed to clear the area in a short space of time.

In 1365, an opportunity arose when a pretender to the Castilian throne called Henry of Trastámara asked Charles for assistance against his half-brother King Pedro the Cruel. Sensing an opportunity, Charles ordered du Guesclin to recruit every routier he could find and sent this new army to Spain to assist Henry.

At first, du Guesclin’s army performed well and many fortresses were captured, including Briviesca, Magallon and even the Castilian capital of Burgos. Henry was delighted with the results and proclaimed du Guesclin as the ruler of Granada, even though the Moors still held that territory. However, as Aquitaine was on the other side of the Pyrenees, it was not long before the English saw another chance to harass the French. Like the war in Brittany, the Castilian Civil War was a sub-conflict of the wider wars with England, and Edward the Black Prince was an ally of Pedro.

Edward led an Anglo-Gascon army into Spain to fight du Guesclin’s force, which led to a famous battle at Nájera on 3 April 1367. The clash was notable for the use of English longbowmen in an unfamiliar landscape away from France and the British Isles. Du Guesclin led a hand-picked vanguard of 1,500 men-at-arms and 500 crossbowmen in Henry’s Franco-Castilian army – outnumbering Edward’s force.

Directly facing him was a division of English archers and infantrymen led by Edward’s brother, John of Gaunt. Captal de Buch, du Guesclin’s defeated enemy from Cocherel, was also present. During the battle, du Guesclin was engaged in fierce hand-to-hand fighting with Gaunt’s division in the centre while chaos raged all around. The English archers inflicted heavy damage on Henry’s light cavalry on the flanks, which eventually caused them and the infantry to flee. Du Guesclin, who was surrounded in the centre, was completely unaware of the rout and only surrendered when he was informed of the situation. By the time the battle was over, a quarter of his force was dead and virtually everyone else was injured.

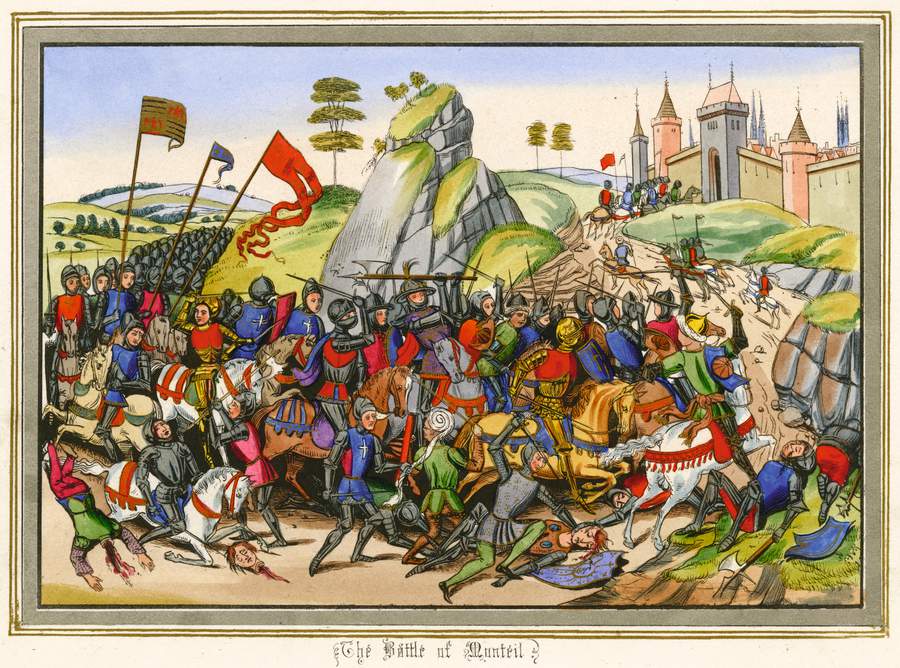

Nájera was a painful defeat but once again Charles V quickly ransomed du Guesclin as he was now considered to be invaluable. The Breton returned to Spain with a larger army and this time his fortunes changed when Edward left Spain after Pedro refused to pay the English campaign costs. Henry was now in a stronger position and at the Battle of Montiel on 14 March 1369, Pedro was decisively defeated. The victory was largely du Guesclin’s achievement; he led Henry’s army and used enveloping tactics to crush Pedro’s Castilian-Moorish force. Despite this success, the greater drama came immediately after the battle.

Pedro fled to Montiel Castle and attempted to bribe the pursuing du Guesclin to allow him to escape. Du Guesclin agreed but he also informed Henry, who also bribed him to lead him to Pedro’s tent. Once inside, the brothers began a fight to the death with daggers. Pedro gained the upper hand but at the last moment, the compromised du Guesclin took hold of Pedro, which allowed Henry to kill him. During this complicity in regal fratricide, du Guesclin is alleged to have said: “I neither put nor remove a king, but I help my master.”

This wilful abdication of responsibility reaped its dubious reward and a grateful Henry proclaimed du Guesclin as Duke of Molina and sealed the Franco-Castilian alliance. With his work completed, du Guesclin returned to France to once more aid his king.

Constable of France

By 1370, Charles V was ready to take the fight back to the English. Known as ‘Charles the Wise’, he was physically frail but nevertheless highly educated and pragmatic. He stopped sending the crippling ransom payments that were still owed for John II’s English imprisonment and reorganised his taxation system to fund a new force that was arguably France’s first standing army. This consisted of 3,000-6,000 men-at-arms and 800 crossbowmen. He also gave orders for townsmen to practice archery and to keep castles in good repair.

These preparations were made for a military offensive, but not one that involved any direct confrontations with the English. Charles knew that his armies could not defeat his enemies in open battle and so he contrived to win back his lost territory by adopting a scorched earth policy, guerrilla raids and forbidding his troops to openly engage the English.

Perhaps his most radical strategy was breaking with knightly chivalric traditions by appointing commanders who had proved themselves as captains of frontier garrisons or even as routiers. These men would not be paladins but hard-nosed professionals, and chief among these soldiers was du Guesclin himself.

In 1370, Charles appointed the former squire as Constable of France. This ancient office made du Guesclin the highest officer in the land after the king and effectively commander-in-chief of his military forces. Senior members of the nobility usually filled the position, but Charles needed a seasoned soldier who could appeal to the routiers to fight for him. In this regard, and despite his patchy military record, du Guesclin was perfect. He agreed with Charles’s strategy and from the outset, the French began to achieve successes against their ancient foe.

The test came almost immediately when Sir Robert Knolles launched a large raid into the Île de France and devastated the countryside up to the gates of Paris in September 1370. From his palace, Charles V could even see the rising smoke of burning villages, but he still refused to engage in battle. Du Guesclin deliberately waited until the enemy split up and then pounced on a contingent of 4,000 men led by Sir Thomas Grandison at Pontvallain on 4 December.

After a night march, the fight began at dawn with the French initially taking heavy casualties but the English were eventually either killed or captured, including Grandison. A similar fight took place at a nearby engagement at Vaas and Knolles was forced to call off his raid. The pursuing du Guesclin subsequently killed around 300 English soldiers outside the gates of Bressuire.

Although it was a relatively small battle, Pontvallain broke the decades-old aura of English invincibility and du Guesclin proceeded to reconquer Poitou and Saintonge between 1371-72 and even temporarily overran Brittany in 1373. During these campaigns, and the ones that followed for the next five years, du Guesclin slowly clawed back French lands and made inroads into English Aquitaine. There were even French naval raids on English home territories such as Guernsey, Rye, Plymouth and Lewes.

Du Guesclin’s finest hour as constable arguably came in 1377, when he defeated Edward III’s Aquitanian representative Thomas Felton at the Battle of Eymet. So many soldiers drowned after the battle that the area around the River Dropt was known as the ‘Englishmen’s Hole’ for centuries afterwards. After Eymet, du Guesclin came within a day’s march of Bordeaux and took Bergerac.

Although Pontvallain and Eymet were notable battlefield victories, du Guesclin’s successes were largely won by deliberately avoiding the English where he could. Consequently, the English were left with no one to fight and they wasted vast resources marching through French territory on campaigns that would ultimately amount to nothing. The most costly of these campaigns was arguably John of Gaunt’s 1373 raid, which struck out from Calais to Bordeaux and covered 965 kilometres in five months. The English cut a huge swathe of destruction through central France but they lost 5,000 men out of 11,000 and huge amounts of supplies without capturing a single town or fighting any battle. Consequently, by the mid-1370s, English territory in France had shrunk to the area around Calais and a reduced Aquitaine.

This achievement was due to the combined work of Charles V and du Guesclin but this military odd couple would end their partnership on very poor terms. Although he had loyally served the French crown for decades, du Guesclin was proud of his Breton roots and when Charles confiscated Brittany in 1378, the constable opposed the decision. He carried out the subsequent campaign into his homeland half-heartedly. The constable now lost favour with the French king for the first time and was dispatched far from court to Languedoc to suppress the routiers in the region. While he was besieging Chateauneuf-de-Randon, du Guesclin caught a fever and died aged around 60 on 13 July 1380. The sickly Charles died three weeks later but not before he had given orders for his loyal constable to be buried among the kings of France at the Basilica of Saint Denis.

This final act turned the already highly popular du Guesclin into a folk hero among both the French and Bretons. Here was a man who had fought his way from the status of a lowly squire, to being considered the equal of kings and in the process liberating the majority of France from a relentless invader. The kingdom would not see his like again for half a century.

For more stories of historical warriors pick up a subscription of History of War and save money on the cover price! For more information visit: www.myfavouritemagazines.co.uk