Guarding over the Dardanelles for about 400 years, the famed Ottoman super cannon is arguably one of the most important guns in history.

Like Darth Vader’s Death Star, the Dardanelles gun imposed the overbearing, threatening presence that tacitly boasted of imperial grandeur of which pop-culture villains could only dream. This pass was assuredly Ottoman. Its predecessor would break down the walls to an empire that had continued since Augustus Caesar and it – itself – would deter another up-and-coming empire almost half a millennium later.

The generic term Ottoman super cannon, when used by historians, confusingly refers to a few separate bombards that were used by the Ottoman Empire but dating from the same period. The first one was nicknamed Basilica and the last one – the fodder of pub trivia – is the Dardanelles Gun, or Şahi topu.

The Dardanelles gun is a super cannon designed as a bombard for use in siege warfare. The gun weighs 16.8 tons and measures 17 feet in length with a diameter of just under 3.5 feet and it fired a massive marble shot at a range of one-and-a-half miles.

The gun now sits in the Royal Armouries in Fort Nelson, Hampshire, and was gifted to Queen Victoria in 1866 by Sultan Abdülâziz. It sits disassembled under a canopy for public viewing. In light of the technologically advanced weapons that have emerged in the last century alone, it’s difficult to remember how these massive superguns once changed history.

The gesture was especially kind considering that it had been used 59 years earlier, in 1807, by Ottoman forces to blast away British ships that were attempting to deter the Ottomans from entering into a war with Russia, ensure freedom of movement for British ships, and hopefully free-up shipping lanes. The operation occurred only two years after the Royal Navy had triumphed at the Battle of Trafalgar.

Under the command of Vice-Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, the Mediterranean Fleet made preparations for an assault that was ultimately to end in Constantinople (now Istanbul) if need be. Nonetheless, he chose to use a small portion of the fleet under the command of Sir John Thomas Duckworth to carry out the attack.

The British Mediterranean Fleet sailed into the Dardanelles and into the Sea of Marmara. Initially riddled with mishaps such as HMS Ajax catching fire, then later running aground, and then finally blowing up altogether; but then events seem to unfold in their favour. The Ottoman defenders were almost non-existent and put up a pitiful resistance as he had arrived during the end of Ramadan.

The Ottoman guns persisted. And although the British fleet experienced some success at the beginning, the Ottomans eventually inflicted significant damages on the fleet. 28 British sailors were killed through the bombardment led by this gun and Duckworth was then forced to withdraw.

How could a modern navy – the most powerful of its day – be deterred by such outdated weapons?

Basically, the Ottomans knew that the guns would work because they had before. The super cannon that now sits in the Royal Armouries was forged in 1464 by Munir Ali on the example of those used eleven years earlier. Designed by the Hungarian cannon founder Orban and used in the Siege of Constantinople in 1453, the earliest three Ottoman super cannons were responsible for bringing down its walls.

But history could have been completely different. Initially, the siege engineer, Orban, offered his services to the Byzantine Empire, but they refused his help because they could not afford his high wages and did not possess the raw materials necessary to produce such a weapon. Super cannons had started to be common in European siege warfare, but Orban intended to take the concept to its extreme. He then played the other side and offered his services to Sultan Mehmet II. The Sultan asked him if he could produce a weapon strong enough to smash the walls of Constantinople, to which Orban replied:

I can cast a cannon of bronze with the capacity of the stone you want. I have examined the walls of the city in great detail. I can shatter to dust not only these walls with the stones from my gun, but the very walls of Babylon itself

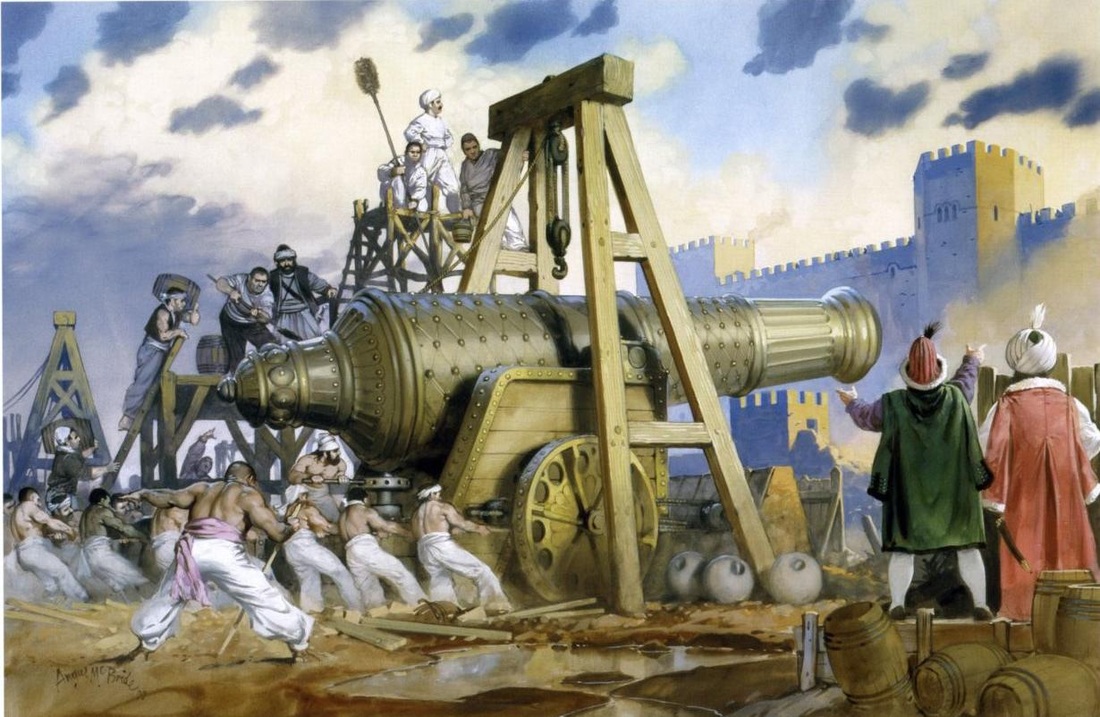

Orban began his work at Edirne to create one of the largest guns ever built. Workers dug a gigantic casting pit in the ground and began pouring bronze into the mold. The monster that emerged would be named by its creator, “Basilica.” He would continue to produce other batches of guns until the time of the siege, but none were as big as Basilica.

Basilica measured over 27 feet in length and weighed enough that it reportedly had to be carried – disassembled – by a team of 60 oxen and an accompanying crew of up to 400 men. Its barrel was 30 inches in diameter and its bronze walls were 8 inches thick. It fired a massive marble ball that was designed to knock down fortifications with one shot.

Despite this, its effectiveness was largely psychological at the beginning. Each of the super cannons were surrounded by smaller caliber weapons in around 15 batteries positioned around the walls of Constantinople. Basilica’s shots were followed by volleys from smaller cannons that did a large portion of the work.

Orban’s ambition was far ahead of the forging capabilities of the time. The workers from the foundry also accompanied the guns on the battlefield and often had to repair them on location. Basilica itself was capable of firing only seven shots a day for fear of it cracking. Even then, the gun had to be cooled with massive amounts of olive oil and cleaned frequently.

Once cooled, it would take large crews a long time to reload and prepare the next shot. This glacial pace allowed the Byzantine defenders enough time to patch up holes in the wall almost as quickly as the next shot could be prepared. Eventually, however, they were overwhelmed.

With the fall of Constantinople came the fall of the last remnants of the Christianized Eastern Roman Empire. When the Roman Empire split in 330 CE, the co-capital of the eastern half had moved to Constantinople and this imperial lineage came to an end with its fall in 1453 to Mehmet II, fulfilling a prophecy of the Prophet Muhammad that Rome would fall to a Muslim army. As such, he began to bear the title Kaysar i-Rum, or Caesar of Rome. Of course, none of this would’ve been possible without the aid of the Ottoman super cannon.

Whatever their effectiveness was, these guns were more status symbols than anything else. They were designed to be so massive, so overwhelming, that enemies could not help but feel belittled by the size. The threat that they could be turned against you was far better of a deterrent than their actually employment. It’s no wonder that the 20th Century’s megalomaniacal dictators lusted after their own WMDs as declarations to the world, but they could never reach the effectiveness of the Ottoman guns.

Even when they sat silent the were still in active duty, proclaiming the dominance of the empire.

For more on history’s defining weapons, pick up the new issue of History of War or subscribe now and save 30%.

Sources:

- Nicolle, David, and Christa Hook. Constantinople 1453: The End of Byzantium. Oxford: Osprey Military, 2000.

- Hodgson, Marshall G. S. The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization. Vol. 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974. 560-564.

- Kinross, Patrick Balfour. The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire. New York: W. Morrow, 1977.

- Tucker, Spencer. A Global Chronology of Conflict from the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO, 2010. 1054-1055.

- Crowley, Roger. “The Guns of Constantinople.” History Net – The Guns of Constantinople. July 30, 2007. Accessed March 20, 2015. http://www.historynet.com/the-guns-of-constantinople.htm.