Perched on a sandbank on the mouth of the River Humber, Ravenser Odd (or Ravensrodd) was Medieval Yorkshire’s own wretched hive of scum and villainy where merchants of flexible morals and ruthless ingenuity acted as little more than pirates. Appropriately enough, it was born with the Vikings.

First noted in the 7th century under the evocative name Hrafn’s Eyr (Old Norse for “raven’s tongue” from where we get Ravenser), the wider headland of Spurn Point was long a staging point for Norse fleets coming and going from Northern England in the Viking Age, ending, symbolically with the departure of Harold Hardrada’s defeated army from this same stretch of blasted coastline in 1066.

Before the stones of Ravenser Odd hit dirt, a smaller Danish community of Ravenser (known, confusingly, as Ravenser Old or Ravenser Alt) was recorded around the same headland, but nothing compared to the town that sprung up in the 1230s from the scanty foundations of a few fishermen’s huts on a recently surfaced bank of sand and pebbles. A strange and exposed place – possibly a tidal island linked to the mainland by a causeway – it brings to mind lopsided shacks and uneven boards, a biting wind, the mocking bray of gulls and a constant, inescapable damp.

The town was laid down at the order of William de Forz, 3rd Earl of Albemarle, described by the 19th century antiquarian William Stubbs as “a feudal adventurer of the worst type.” Part of the Holderness estates he had inherited from his mother, the ambitious lord was quick to see the potential of the site as more lucrative revenue stream than farms and fishermen.

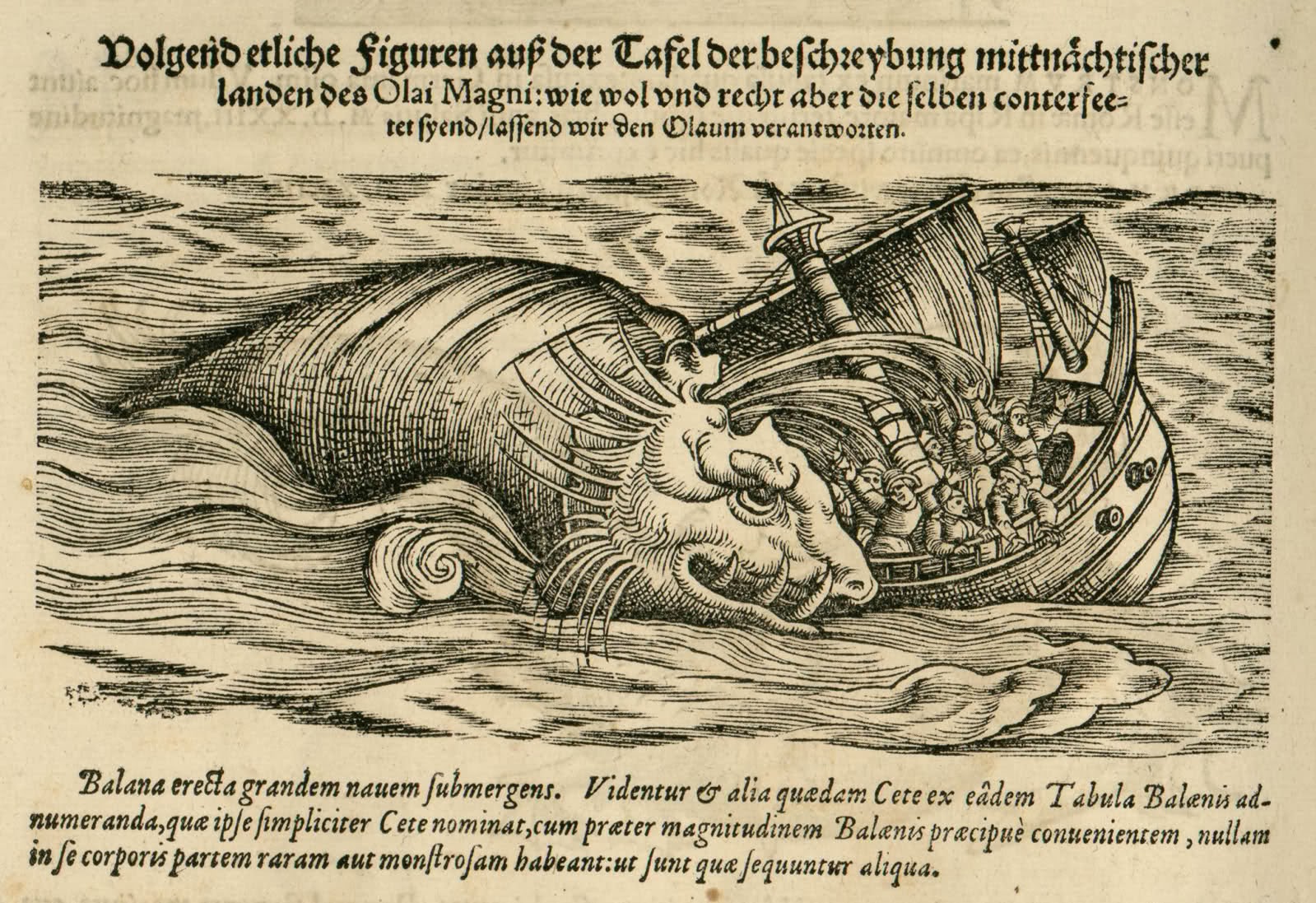

Ravenser Odd was first landing ground available to ships entering the Humber from the icy North Sea (a trade highway that stretched from Scandinavia and the Low Countries through the Baltic to the merchant cities of northern Germany), but if their captains couldn’t be lured to the quay ahead of their destinations downriver (often Grimsby on the south bank or Kingston upon Hull on the north), then the people of Ravenser Odd resolved to make them.

Men in small boats would row out to the incoming ships and entice them to land, often with fear of force, in an act known as ‘forestalling’.

In the The History and Antiquities of the Conventual Church of Saint James, Great Grimsby (1829), the Reverend George Oliver notes:

The rivalry excited by the port of Ravensrodd, situated at the Spurne Point, bore down all opposition, encouraged as it was by the Earl of Alvermarle. His ships rode triumphant over the Humber; he attacked the men of Grimsby in their own harbours, forestalled their markets, and exposed his own merchandise for sale in the town without paying the usual tolls.

In 1298 – much to the horror of Grimsby – the town’s merchants petitioned Edward I for a royal charter, becoming a free borough. Perhaps mindful of the political fallout of such an act, the price was set at £264 compared to the £100 paid by Kingston upon Hull for the same rights. (£100 incidentally, was the sum the burghers of Grimsby estimated that Ravenser Odd was depriving of them every year.)

Its charter – and future agreements – granted the merchants of Ravenser Odd exemption from taxes as they traded across the country, and made the town a world unto itself with a mayor, court, chapel, prison, gallows, wharfs, tanneries, warehouses, a twice weekly market and an annual fair. Growing in stature over the next few decades it was awarded the right to levy dues on ships docked in the harbour, and in return contributed ships and men for Edward’s wars with Scotland. This service in a matter close to the king’s heart – conquest – saw Ravenser Odd take seats in the various parliaments that were summoned piecemeal across Edward’s reign, but it also saw justice turn a blind eye to the trespasses of this little port on the edge of England.

Their piracy and extortion continued as before, but while the sea had once proved their ally in the pursuit of ill-gotten gains, it was slowly becoming an implacable foe. The tides drew the ground – and the dead – from beneath their feet, with bones in the churchyard exposed in ill-omen and its walls collapsing into the mud.

Worse still, it was looted, as Thomas Burton, one time Abbot of Meaux (near Beverley), recalled in the Chronicle of Meaux (circa-1406):

When the inundations of the sea and of the Humber had destroyed to the foundations the chapel of Ravenser Odd, built in honour of the blessed Virgin Mary, so that the corpses and bones of the dead there were buried horribly appeared, and the same inundations daily threatened the destruction of the said town, sacrilegious persons carried off and alienated certain ornaments of said chapel.

By 1332 it was believed that a third of the population had fled the encroaching tides, with the 19th century antiquarian George Poulson quoting a local inquiry called to access the sorry state of Ravenser Odd:

Two parts and more of the tenements and soil of the town by the flux of the water of the sea, (aqua maris,) after inundating the said town, are beaten down and carried away; and that said town by the flux of the water aforesaid is daily diminished and carried away. They also say that many inhabitants of the said town have withdrawn themselves, their goods and chattels, as the dangers there continue to increase from day to day, who were, previously, accustomed to bear the burdens of the said town, and are gone to dwell elsewhere; so that there does not remain a third part of the inhabitants with their goods.

In January 1362 a poetic finale came on the winds as a ferocious storm and unusually high tides unleashed the Great Drowning. The men and women of Ravenser Odd were scattered to the ports they had once plagued, and all that remained of this prosperous – and unprincipled – borough were a warning to sailors of submerged walls that might tear at their keel.

Burton recalled:

With all inferior places, and chiefly by wrong-doing on the sea, by its wicked works and piracies, it provoketh the wrath of God against itself by all measure. […] the said town, by those inundations of the sea and of the Humber, was destroyed to the foundations so that nothing of value was left.

For more curious from Medieval history, subscribe to All About History for as little as £26.

Sources:

- The Lost Towns of the Yorkshire Coast and Other Chapters Bearing Upon the Geography of the District by Thomas Sheppard (1912)

- The History and Antiquities of the Conventual Church of Saint James, Great Grimsby by George Oliver (1829)

- The History and Antiquities of the Seigniory of Holderness, in the East-Riding of the County of York by George Poulson (1840)