If we want to understand Catherine of Aragon, we must start by understanding her mother. The formidable Isabella of Castile, who combined a fiery national pride, an iron will and an unwavering dedication to the teaching of the Catholic Church (for which she was later invested with the title ‘Servant of God’). Isabella had to fight for the throne of Castile and, after her marriage to Ferdinand II of Aragon in 1469, she retained the exclusive right to reign in her own territory.

The union of the two crowns was the basis of Spain’s emergence as a major power in Europe, with access to the political and mercantile life of the Mediterranean world and the thriving economies of the Netherlands, England and the Baltic. More than that, thanks to Isabella’s patronage of Christopher Columbus, Spain played a pioneering role in the establishment of European global empires. But the sovereigns’ gaze was not only turned outwards; Ferdinand and Isabella were determined that their territory should be entirely Catholic. They brought to a conclusion the long Reconquista, the driving of the Moors from Spain. Granada was an Islamic kingdom in the south of Iberia and it had contracted over 500 years due to intermittent pressure from the Christian north. Ferdinand and Isabella completed the conquest in 1492.

Although unable to go into battle herself, Isabella often appeared before her troops in part-armour to encourage and inspire them. She was closely involved in aspects of military life, such as organising field hospitals. Not content with this victory, the joint rulers were intent on a religious purge of their territory. They expelled all Muslims and Jews who would not convert and those who did convert were subjected to rigid interrogation to ensure that their change of allegiance was genuine. This called for a special religious judicial system with extensive powers.

With that, the Spanish Inquisition was born, a frightening fusion of church and state authority that was responsible for the imprisonment and death of thousands of victims before its abolition in the 19th century. Isabella was aware of the power of her religious programme, and she used the imperative of holy war and her role as the agent of God to solidify the support she needed. She created a messianic image of herself that promised to undo the ills of the past and lead Spain on its true, Christian, course.

Catherine was her mother’s daughter – intensely loyal to her dynasty and her church. As the younger female child of the rulers of a powerful new nation, she was an important pawn in international diplomacy, but she had also been brought up to see herself as having a mission to support the Catholic crusade led by Spain. Her marriage to the heir to the English throne was eagerly sought by both Ferdinand and Henry VII of England.

Henry, whose claim to rule rested only on conquest and who was plagued by Yorkist plots, coveted the cachet given to his dynasty by this impressive union. Ferdinand valued English support against France, which stood in the way of Spain’s further expansion. In the autumn of 1501, Catherine arrived in England and was married to Arthur, Prince of Wales. The groom had just passed his 15th birthday. Catherine was nine months older. Just over four months later, she was a widow after Arthur died at Ludlow where he was performing his princely duties.

Catherine spent the next seven years in limbo. Ferdinand and Henry were reluctant to break off the alliance and it was arranged that Catherine should marry the English King’s second son, Henry, Duke of York – when he was old enough (he was only nine at the time of his brother’s death). It was a wretched time for the lonely girl in a foreign land and her grief was made worse when, at the end of 1504, news arrived that her beloved mother had died. The two kings haggled and argued over her fate. The marriage was on and then off. Impotent and frustrated, Catherine was not content to be sidelined. Convention demanded that she should wait patiently upon the decisions of her father and potential father-in-law. That was not Catherine’s style.

She intervened in diplomacy, going so far as to demand that Ferdinand sack his ambassador, as he counselled abandoning the marriage treaty. Catherine’s fate was still undecided when Henry VII died in April 1509. One of the new King’s first decisions was to marry his widowed sister-in-law.

It was important to those closest that the marriage should be a success. For Henry, ‘success’ meant securing the Tudor dynasty and strengthening Anglo-Spanish ties. He was set on regaining England’s role as a lead player in European affairs that had been lost during the Wars of the Roses. He shared Ferdinand’s understanding of France as his main obstacle.

All began well. The lusty, vigorous, athletic, teenage King brushed away the cobwebs of his father’s cautious, frugal, pragmatic, financially oppressive policy and was determined to be a ruler in the adventurous, romantic mould of King Arthur and Henry V. From his earliest years, Henry was brought up on those heroic legends.

Catherine’s position could not have changed more dramatically. She reported to her father that life had become one long holiday, a time of banquets, dances, tourneys and hunting. Thomas More, in a flattering eulogy, set the regime change in wider perspective:

The nobility, long since at the mercy of the dregs of the population… whose title has too long been without meaning, now lifts is head, now rejoices in such a King, and has proper reason for rejoicing. The merchant, heretofore deterred by numerous taxes, now once again ploughs seas grown unfamiliar. Laws, heretofore powerless – even laws put to unjust ends – now happily have regained their proper authority. All are equally happy. All weigh their earlier losses against the advantages to come.

It took only a few months for sad reality to set in. Catherine was delirious to discover herself pregnant in August 1509 but five months later, she miscarried a daughter. She was overwhelmed with a sense of failure, so much so that she concealed the news from her father for as long as possible. Fortunately, a second child was, by then, on the way. On 1 January 1511, she gave birth to a boy. A delirious Henry really pushed the boat out in celebration. A magnificent international tournament was held at Westminster and the King made a pilgrimage to the shrine at Walsingham. Ten days later the infant Prince was dead. Failure again – and this time more humiliating. It has often been thought that Henry began to question the validity of his marriage in the 1520s but doubts began to creep in much earlier. In taking Catherine as his wife, Henry had flouted his father’s dying wishes, the advice of his council and the rules of holy church. Could it be that the loss of his children signified divine displeasure? For the time being, the King stifled any such misgivings.

Catherine encouraged him to do so and threw her weight behind diplomatic manoeuvres directed towards Anglo-Spanish war with France. She was more eager than ever to justify her raison d’etre as a political link between Spain and England and worked behind the scenes to disarm the peace party on the council. She was a willing pawn in the game of military diplomacy that was now played out. But it was not a game between equals. Ferdinand, a master of duplicity, had waited long to draw England into his ambitious schemes. Through Catherine, he encouraged Henry’s bellicose dreams of regaining land in Aquitaine that had once been annexed to the English crown, while his real intention was to use the English invasion as a diversion to cover his own assault on the Pyrenean kingdom of Navarre.

The campaigning of 1512 was remarkable for extravagant bravura and humiliating disaster. Henry doubled the size of his navy. When he heard that James IV of Scotland had ordered the building of the Michael in France, the biggest warship afloat, he immediately commissioned the Henry Grace à Dieu to outclass it. The glorious game of war was celebrated in jousts and court festivities and when the army embarked at Southampton, he went into raptures over the scene:

To see the lords and gentlemen so well armed and so richly apparelled in cloths of gold and silver and velvets of sundry colours, pounced and embroidered, and all petty captains in satin and damask of white and green and yeoman in cloth of the same colour, the banners, pennons, standards… fresh and newly painted with sundry beasts and devices, it was a pleasure to behold.

But the troops sent to south-west France were deserted by their Spanish allies and returned with their tails between their legs while naval engagements in the Channel cost many lives and achieved nothing.

Inevitably, relations between the allies were strained but Henry was set on his heroic adventure and Catherine played her discreet part in oiling the wheels of the war machine. She was particularly attached to the navy and, as her mother had emboldened her soldiers and personally involved herself in administrative detail, so Catherine maintained contact with naval captains. At one point she negotiated with Venice to hire galleys. Nothing came of this, but her back-stairs diplomacy in Rome bore more important fruit. Through Cardinal Bainbridge, Archbishop of York, she brought pressure to bear on Pope Julius II to threaten James IV with excommunication if he intervened in England to help the French. The resulting Anglo-Scottish conflict was a by-product of the convoluted state of European politics.

In response to France overrunning part of north Italy, Julius had formed the Holy League embracing Spain, the Holy Roman Empire and England ostensibly in defence of the Church (though each participant had his own objectives). James IV was torn between his obligation as a Catholic monarch, his alliance with England (he was married to Henry’s sister, Margaret) and his commitment to the traditional Auld Alliance with France. Eventually, it was the latter – plus some pretty inflammatory correspondence with Henry – that made the decision for him.

The main invasion of France was led by Henry in person and was planned for the summer of 1513. On 15 June, the King and Queen set out from Greenwich on their way to Dover, where Henry was to embark with his grand army. Their first halt was at Canterbury where they prayed at the shrine of St Thomas à Becket (which would be demolished by Henry VIII 25 years later). While the King crossed the Channel, he deputed Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, to deal with the Scottish threat and he left Catherine in overall command in England as Regent and Governor.

At last, Isabella’s daughter was in her element. Nature may have deprived her of her role as a royal mother but she would now show that she was a military champion, inspiring her troops, planning the overall campaign against the Scots and attending to the necessary logistics. She oversaw the despatch of Surry and his army by land and a supporting seaborne force with reinforcements and heavy artillery. The total English contingent numbered around 20,000.

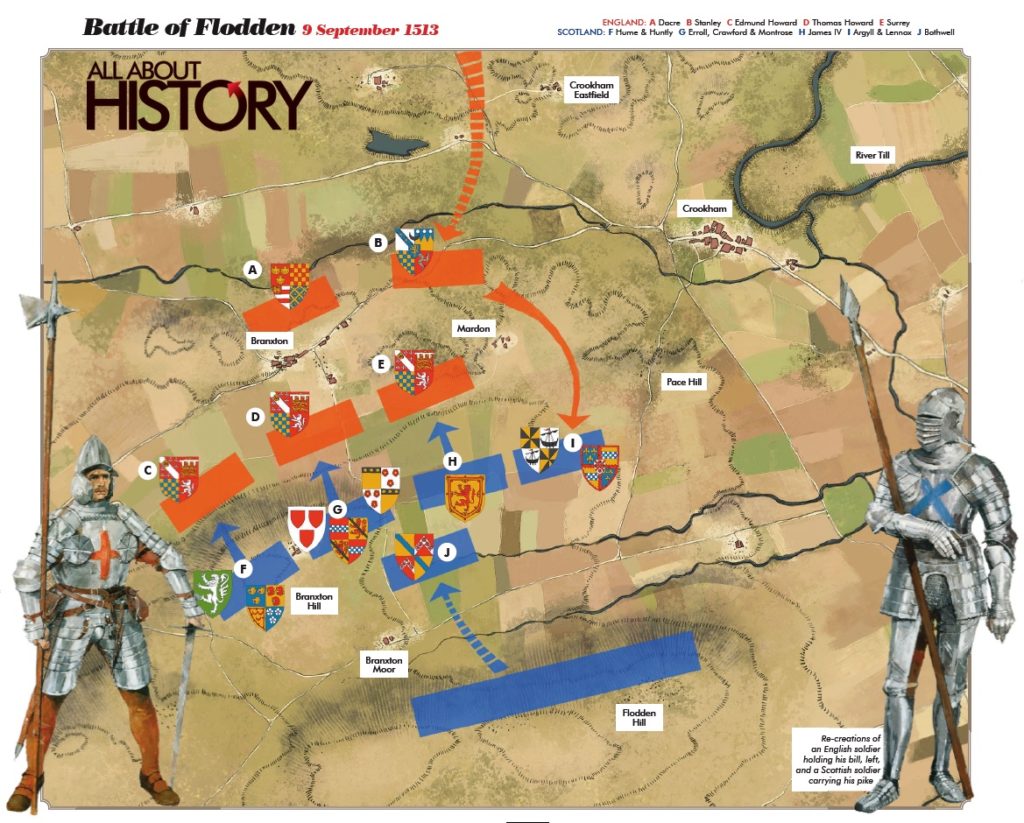

Catherine also presided over the council, still not united in enthusiasm for the venture, and sent regular reports to her husband. But that was not all. Careful contingency plans were set in motion in case the Scottish advance was not effectively halted by Howard. A secondary army was raised in the Midlands and a third, under Catherine’s personal command, formed a line of defence in the home counties. When her force was mustered, the Queen rode out to deliver a rousing speech, “in imitation of her mother” as one observer reported. Did she, we may wonder, deck herself in part armour like the redoubtable Isabella? In the event, elaborate defensive measures proved unnecessary. On 9 September, Surrey’s men won an overwhelming victory in the largest ever Anglo-Scottish confrontation at a place called Flodden Field or Branxton Moor.

This encounter has been referred to as the last Medieval battle fought on British soil because of the weaponry used and the rules of chivalry which, in some measure, governed it. The Scots had crossed the border and enjoyed considerable success in early actions. After some unaccountable delay, they had taken up an excellent defensive position on Flodden Hill, some 2,000 metres to the south of the Northumberland village of Branxton, lying four kilometres south east of Coldstream. The terrain was hilly, with high ground and steep-sided valleys running roughly east to west.

In an effort to dislodge the enemy, Howard turned away northwards. The Scots did leave their vantage point but, though the English turned to face them, they succeeded in reaching the next ridge, Branxton Hill. In an exchange of messages via heralds, Suffolk challenged the Scottish King to meet him on level ground and a time and place was appointed for the battle. It was all very honourably arranged. More surprisingly, according to the Scottish chronicler, Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie, as Howard brought his artillery across the River Till, he came in range of the Scottish cannon but James refused to take advantage and ordered his weapons to stay silent. As Pierre Bosquet remarked centuries later about another brave but misguided military decision, “C’était magnifique mais ce n’était pas la guerre” – it was magnificent, but it wasn’t war. It may be that James felt he could be generous. He held the initiative and outnumbered the enemy by some 10,000 men.

On 9 September, after an ineffective exchange of cannon fire, the Scots descended the north side of Branxton Hill to meet their adversaries in hand-to-hand battle as the commanders had agreed. At about 4pm, James began with a sortie against the right of the English line and almost broke it, but Howard sent in his reserve forces and the flank held. Along the rest of the line, bloody battle ensued in soggy ground that severely hampered mobility.

Military historians ascribe the English success to the superiority of their weapons. The Scottish infantry relied on the pike, a spear some three or four metres in length. It was a thrusting tool designed for use against both foot and mounted troops and worked best when the enemy could be prevented getting too close. The English employed the bill, developed from an agricultural implement. It was shorter than the pike and had an axe blade as well as a spearhead. As a cut-and-thrust weapon, it was of more use in the sort of close-contact fighting forced on the combatants by sticky ground conditions of Branxton Moor. The Scots had to abandon their pikes and draw their swords. They were literally scythed down in great numbers. The English right and left wings both pressed home their advantage, almost surrounding the enemy.

Even so, the day was far from won. King James led a furious charge against the standard borne before the Earl of Surrey. Had he reached the English commander, the day would have been his. In fact, he was cut down only a few metres from his quarry. At that, the Scots struggled to escape the field pursued by the baying victors. Losses in Medieval battles are notoriously difficult to establish, since different records quote different figures. At a conservative estimate, we may say that Howard’s army was depleted by some 1,500 men, against Scottish losses of around 10,000. More important politically was the number of nobles and major landowners who perished. The losses of that day were long remembered in folklore.

Round about their gallant king, for country and for crown,

Stood the dauntless Border ring, till the last was hacked down.

I blame not what has been. They must fall that cannot flee.

But, oh! To see what I have seen, to see what now I see,

On Flodden Field.

So wrote one 19th-century poet. An earlier lament (still played today) is the Flowers Of The Forest:

Mourn for the order sent our lads to the Border.

The English, for once, by guile won the day.

The flowers of the Forest that fought aye the foremost,

The prime of our land, lie cold in the clay.

About 300 miles away, en route for the north, Queen Catherine was jubilant at the news. Howard sent her a trophy, part of James’s bloodstained surcoat, retrieved from his dead body, and she forwarded it to her husband. “To my thinking,” she wrote, “this battle hath been to your Grace and all your realm the greatest honour that could be, and more than ye should win all the crown of France.” The Scottish victory came soon after a successful skirmish at Thérouanne on 16 August.

Henry’s army besieging the town saw off a relief force. The event was mockingly referred to as the Battle of the Spurs because of the speed of the French retreat. Henry, too, sent a trophy across the Channel – the Duc de Longueville was an important captive and Catherine arranged honourable quarters for him in the Tower of London. Now she disbanded her troops and set off for Walsingham to give thanks, not only for victory, but also for the fact that she was again pregnant. But the sunlit sky was soon clouded over again. Catherine’s pregnancy was either a misdiagnosis or ended in a miscarriage.

Then, in the spring of 1514, Henry’s allies deserted him. Ferdinand and Emperor Maximilian signed a truce with France. Moreover, a proposed marriage between Princess Mary (the King’s sister) and Ferdinand’s nephew, Prince Charles, was put on hold. Henry seems, at last, to have grasped what diplomacy was all about. It had little or nothing to do with chivalry, loyalty and brotherhood-in-arms and everything to do with self-interest. He, too, sought to salvage what he could from the recent war. A peace treaty was signed with France that involved a substantial cash payment and the marriage of Mary, not to Charles, but to Louis XII. But, yet again, the diplomatic seesaw elevated Anglo-Spanish relations. The aged Louis died within weeks of his marriage. His place was taken by the young and energetic Francis I, who eagerly resumed hostilities in Italy. Events forced Henry and Ferdinand to renew their alliance and once again, Catherine conceived. But in the early days of 1516, her father died and shortly afterwards she was safely delivered of a child – a girl.

Where did all this leave Catherine, now middle-aged and dowdy? She was steadily becoming surplus to requirements. She turned increasingly to religion. Frequenters of the royal court noticed that she seldom attended festivities. Henry now had another companion more in tune with his love of extravagant display in the form of Thomas Wolsey, who gradually took charge of diplomacy and the formation of policy. In November, the Queen went into labour. The result was another girl who died within hours. The Tudor dynastic train had run into the buffers – or was it just a matrimonial siding?

Derek Wilson has written widely on the subject of Medieval and Early Modern Europe. His most recent books are Superstition and Science, 1450-1750: Mystics, Sceptics, Truth-seekers and Charlatans and Mrs Luther and Her Sisters: Women in the Reformation. For more on the Tudors, subscribe to All About History for as little as £26.

Sources:

- G Mattingly, Catherine of Aragon, 1491-99, Jonathan Cape 1942

- B F Weisberger (ed.), Queen Isabel I of Castile – Power, Patronage, Persona, Tamesis Books 2008

- G Tremlett, Catherine of Aragon: Henry’s Spanish Queen, Faber & Faber 2010

- D Starkey, Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII, Vintage 2004