With the war in Ukraine continuing, Dr Mark Galeotti reflects on how the Kremlin should have applied the lessons from its own bloody history

Subscribe to History Of War today for great savings on every issue!

Honorary professor at University College London’s School of Slavonic & East European Studies, with multiple published books on Russian security, foreign policy and state criminality, Dr Mark Galeotti is an expert on the Russosphere, both past and present. His latest book, Putin’s Wars: from Chechnya to Ukraine from Osprey Publishing, out now, analyses how President Vladimir Putin’s military campaigns have reshaped the nation and the world. In light of Russia’s globally condemned invasion of neighbouring Ukraine, here he gives his assessment of the lessons that the president ought to have learned from his country’s own military history: from Nicholas II to Ivan ‘the Terrible’.

Vladimir Putin is well-known for his interest in history. It is one of the few things he apparently reads, and he peppers his speeches with references to past Russian heroes, triumphs and challenges. Indeed, he has paralleled himself variously to such past figures as Tsar Peter the Great, the eighteenth-century monarch who battled Sweden, then the great Nordic military power of the age, and Petr Stolypin, the early twentieth-century prime minister who combined a commitment to reforming his country with the ruthless suppression of the 1905 Revolution.

That said, he is also a strikingly poor historian. He has produced lengthy essays on Russia’s relationship with Ukraine, meant to justify his war, that are as stylistically wooden as they are historically dubious, cherry-picking evidence that seems to fit his argument, and stripping them of context and nuance. He has also encouraged a national narrative of struggle and victory focused on war, with the Second World War – the Great Patriotic War in Russian parlance – as the centrepiece of a heroic tale of military glory. Parade uniforms blend tsarist and Stalin-era aesthetics, school playgrounds sport (deactivated) anti-tank guns of the time, and TV channels like the Ministry of Defence’s Zvezda (Star) serve up an almost unbroken diet of war films.

In this context, it is all the more striking just how far Putin has also managed to misunderstand or ignore so many of the lessons of Russia’s military history, and particularly those learned or understood by six of his predecessors, from the fourteenth to the twentieth century, in his drive to build a twenty-first century military great power.

Prince Dmitry Donskoi: Don’t believe your own myths

With its social media ‘troll farms’ pumping out dubious and disruptive content and its tightening grip on journalism at home, Putin’s Russia has embraced the weaponisation of disinformation in the internet age. There has also been a concerted effort to create narratives that justify Putin’s actions and present Russia in the best light. Of course, every state does this to greater or lesser degrees, but the real problem with this is when you start to believe your own myths. Putin’s February invasion, after all, seemed to rest on assumptions about Ukraine being near enough a failed state and Ukrainians likely to welcome the Russians, that were rooted not in reality but in the Kremlin’s own propaganda.

Putin could have taken the example of Dmitry Donskoi to heart. A fourteenth-century Prince of Moscow during the time in which Russia was ruled by the Mongols, he had been perfectly happy to be one of their local agents until political squabbles in Sarai, capital of the Golden Horde, forced him into rebellion. He assembled the forces of Moscow’s allies and clients and thanks to hard fighting and some cunning subterfuge was able to beat a larger force under Mongol leader Mamai at Kulikovo in 1380.

Dmitry was a politician through-and-through and had made sure that he had both friendly merchants and representatives of the Russian Orthodox Church to hand to spread the tale of victory and to present it as a convincing blow for Russian freedom. This became a foundational tale of Russia’s emergence as a nation, under Moscow.

Dmitry, though, was smart enough not to fall for his own line. When Mamai’s rival and successor Tokhtamysh returned with a new army next year, he made few efforts to resist. Moscow was sacked and burned, Dmitry hurriedly reaffirmed his submission to the Golden Horde, and it would be another century before the Russians threw off the so-called ‘Mongol Yoke’ – but thanks to Dmitry’s cold-eyed realism, Moscow remained the heart of the new state.

Tsar Ivan the Terrible: Don’t punch above your weight

Putin has often been described as punching above his weight, taking a country with a GDP roughly equivalent to Spain’s (although the measures is admittedly deceptive) and a defence budget that equals Britain’s (although this is even more deceptive, as it is based on ruble-to-pound exchange rates) and making people treat it like a military great power. For years, this stood him in good stead, allowing him to face down the West and play a disproportionate role on the world stage. However, eventually this does mean that others will take your posturing at face value, and you will find yourself treated accordingly.

Ivan IV, known as Grozny – usually translated as ‘the Terrible’, although ‘the Dread’ or even ‘the Awesome’ are more accurate – was at once the maker of the Russian state and almost its breaker. Although the public image is shaped by his latter years, as he descended into violent and paranoid madness, the first part of his sixteenth-century reign was marked by the foundation of many of the institutions of today’s Russian state. For example the modern MVD, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, is an evolution of his Banditry Office, just as MID, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, explicitly dates itself back to his Ambassadors’ Office. Ivan also established Russia’s first standing army, the Streltsy (‘Shooters’ or ‘Musketeers’), and invested heavily in what would become a traditional Russian strength, the artillery.

He used these in a variety of foreign wars, including the successful conquest of the Kazan Khanate in 1551-52. However, his expansionism and the rising profile of Muscovy’s military power meant that, like it or not, he became embroiled in struggles with nations rather more formidable than the khanates of the east. Ivan would fight wars over Astrakhan with Turkey (1568–1570) and Livonia with a shifting coalition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Sweden and other allies (1558–1583) in just a prelude to what would be a series of subsequent conflicts, many of which would end badly for Russia. Ivan had wanted Russia to be a player on a wider stage, but he should have thought twice as to what this meant, as it meant Moscow was now up against great powers with capabilities beyond its reach.

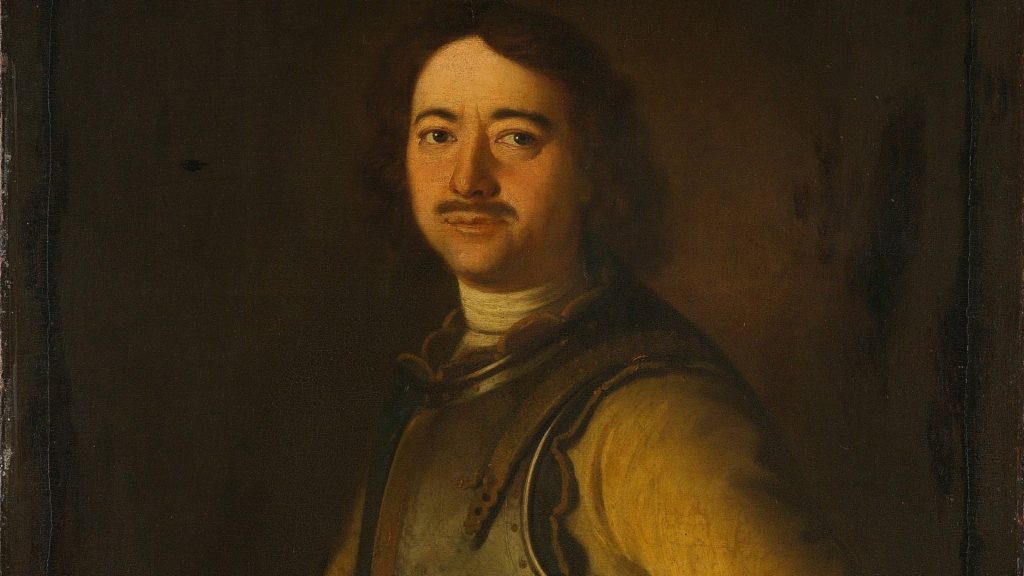

Tsar Peter the Great: Don’t forget to modernise

Peter was obsessed with the notion of Russia finally becoming a naval power. To this end he even because the first tsar to travel beyond Russia’s borders, with his ‘Grand Embassy’ of 9 March 1697 to 25 August 1698, a diplomatic mission that saw him travel to both the Netherlands and England, the pre-eminent maritime nations of the time. In London, between marvelling at parliament (although deciding that “English freedom is not appropriate” for Russia), he visited the royal dockyards at Deptford, studied how modern naval artillery was made and used at Woolwich Arsenal and hired engineers who would be able to help him build his fleet. Which he did, and by his death, Russia had a navy with 32 ships of the line, and over a hundred other vessels.

However, the point was precisely that Peter was looking for technologies, skills and even weapons effectively bought off the shelf. Although he made some efforts to make Russia look more modern, demanding that his nobles affected European dress and shave their beards, and hiring Italian and French architects to build his gracious new capital of St Petersburg, he never seriously addressed the structural constraints preventing Russia from developing.

Too often, he was simply relying on what he could buy and copy from the West, not building the kind of scientific and cultural capital to allow Russia to compete. Therefore, Peter’s Russia – like Putin’s – was condemned always to lag behind the most modern technologies, and forced to rely on quantity when it could not compete in technology.

Tsar Nicholas I: Plug the technology gap

In Ukraine, the influx of NATO weapons and Russia’s need to raid old stockpiles to arm new units mean that just as Kyiv is beginning to field a 21’s century army, Moscow’s is sliding back into the twentieth. Mobile, long-range rocket systems such as US HIMARS and British-supplied M270s mean that Russian artillery and supply lines are now being hit with virtual impunity, while Javelin and NLAWS missiles have neutralised much of Russia’s vaunted tank fleet.

This is hardly the first time a technology gap has been crucial. In the Crimean War (1853-56), the armies of Tsar Nicholas I found themselves facing the most advanced European military powers of the time, Britain and France. Steamships, railways and telegraphs enabled the allies to supply, reinforce and coordinate their armies much more effectively. Rifles such as the British Enfield and French Minié had a massive advantage in range and accuracy to the old-fashioned muskets most of the Russian soldiers were still using.

Meanwhile, in the northern naval operations to blockade Russian trade ports – which were actually of much greater significance than the bloody side-show in Crimea – the gap between naval technologies was at least as obvious. This was signalled in the very first engagement in , when an Anglo-French flotilla was able to destroy Bomarsund fort on the Russian-held Finnish Åland islands with humiliating ease, as their cannon outranged even the heavy coastal guns in the fort.

Nicholas was a soldier by training and had already been concerned about the security implications of Russia’s growing backwardness. He had toyed with fundamental reform to try and modernise and industrialise the country, but held back for fear that it would destabilise the state. He died during the war and his successor, Alexander II, embarked on a serious, although ultimately incomplete effort to address this – albeit one which did indeed stir up serious unrest and the terrorist movement that assassinated him in 1881.

Tsar Nicholas II: The dangers of being in command

Nicholas I was an unbending martinet, but he was at least a trained soldier; his namesake, who succeeded to the throne in 1894, demonstrated what could be considered the worst possible combination of being both incompetent and dutiful. Nicholas II had the misfortune to preside over a Russian Empire that was increasingly anachronistic, which was going through a belated and partial industrialisation that at once undermined the old order without having yet been able to bring forth something new. A disastrous war with Japan (1904-5), which had expected to be an easy triumph, showed how even to the east Russia faced powers which were modernising more quickly.

When Russian became embroiled in the First World War in 1914, again the technology gap would prove crucial, as German machineguns and rapid-fire cannon decimated Nicholas’s forces. In September 1915, he fatefully made himself commander-in-chief, both because he felt it his duty and also because he hoped that the glory of what he still believed would be a Russian victory could help salvage the legitimacy of his regime. Instead, he became associated with bloody defeat after bloody defeat, and appeared to have nothing to offer but the hope that some kind of victory was just over the horizon.

In March 1917 (February by the old calendar Russia still used at the time), while risings were ripping through the cities, the tsar’s train was stopped at Pskov and a delegation under army commander General Nikolai Ruzsky induced him to abdicate (“if you do not sign, I will not be responsible for your life,” Ruzsky warned.) Tsarism collapsed, the Bolsheviks would subsequently seize power, and Nicholas and his family would be executed in July 1918.

The president of Russia is commander-in-chief, and Putin himself has very clearly made this war his own. He even let a meeting of the Security Council, at which he browbeat his senior officials into supporting his line, be televised to underline his own centrality, and the whole strategy of the invasion reflected his assumptions about Ukraine rather than the doctrine whereby the generals plan and fight their wars. He thought it would be a quick victory, won in a couple of weeks. Now, he – like Nicholas II – is at once in command yet unable to develop any kind of strategy seemingly able to turn the war around. A new ‘February Revolution’ may well be a long way away, if it ever materialises, but nonetheless the fate of the last tsar may prove one last cautionary tale for today’s Russian autocrat.

Dr Mark Galeotti is an honorary professor at University College London’s School of Slavonic & East European Studies and his latest book, ‘Putin’s Wars: from Chechnya to Ukraine,’ is out now.