In October 1941, four months after the Wehrmacht invaded the Soviet Union, Adolf Hitler stood before a packed auditorium at the Sportpalast, Berlin. The largest meeting hall in the city, with some 14,000 spectators, was festooned with swastika banners and further ‘Nazified’ by way of a dramatically-lit, 20-metre-wide theatre prop in the shape of a golden eagle. It hovered over Der Führer, seemingly radiating power and purity. This was Hitler’s altar and before it he delivered the following sermon.

“Today, I can say that the enemy is broken and will never rise again! Her power had been assembled against Europe, and would have been a second storm of Genghis Khan. That this danger has been averted, we owe to the bravery, endurance and sacrifice of the German soldier!” His histrionic version of events was met with fanatical applause. His enemy, though, was far from broken.

By May 1945, the “Sieg Heils” that had echoed around that room had been replaced by the chilling war cries of Soviet infantrymen as they smashed their way into Hitler’s sacred temple and onto the very stage he had preached from. “Ura!” they screamed as they hunted down the last of his disciples holding out in the building, going about their murderous work with bayonet, grenade and rifle butt. The Red Army wanted vengeance for the bloodletting at Stalingrad.

For the soldiers of the Red Army that stage, more so even than the Reichstag, symbolised Nazi power. Its capture meant not just the end of the war but also the death of National Socialism – the ideology that had been responsible for the slaughter of 27 million Russian citizens. For the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, however, the real prize was the capture of the prestigious German capital itself.

The idea that the Soviets might seize Berlin and bring an end to World War II in Europe had become a distinct possibility by the start of 1945. The success of the Red Army’s January offensive had seen it smash through 500 kilometres (300 miles) of German-held territory in just 20 days. By 5th February, its troops began to cross the Oder river, the last great natural barrier before Berlin. Once on the other side, however, and just 60 kilometres (37 miles) from Hitler’s capital, they stopped.

The Soviet advance had been so rapid and the fighting so intense, that the successes had left the Red Army short of ammunition and fuel. It would take more than two months of resupply and reinforcement before it was ready for its final push of the war.

The pause in slaughter gave the Nazis time to reorganise, too. Reserve units were cobbled together from whatever troops were left and whichever civilians could be press-ganged into service. Wounded soldiers were ordered from their hospital beds and army clerks sent to combat units, while men as old as 60 and boys as young as 13 were drafted into the newly-formed Volkssturm militias. Those who refused were executed.

In the end, the Nazi high command managed to sweep together about 760,000 troops. Many were sent to join the 9th Army at Seelow Heights, the highlands east of Berlin, to help build elaborate defences there. In the plains before them as these troops worked, the Soviets gathered together an army of 2.5 million men, more than 6,000 tanks and 40,000 artillery pieces. The clock was ticking on what would be the bloodiest showdown in history. By the time Berlin fell, hundreds of thousands of people

lay dead.

British prime minister Winston Churchill also wanted to capitalise on this brief pause. He saw it as an opportunity for the West to seize both the initiative and Berlin itself. By late March, the Western Allies had crossed the Rhine, and were themselves just 100 kilometres (60 miles) from the city. “If the Russians take Berlin,” Churchill warned US President Franklin D Roosevelt on 1st April, “may this not lead to grave and formidable difficulties in the future?”

Churchill, as it would transpire, was very much focused on the future and what a post-war map of Europe should look like. He urged the Americans to take the city. The US high command, though, under General Dwight D Eisenhower, wasn’t keen. The mauling his troops had taken during the Battle of the Bulge that winter, when Hitler had launched his final counter-offensive in the west, had left him wary.

When Eisenhower asked what casualties he could expect if he attacked Berlin, one of his generals told him 100,000. It was an unthinkable figure. Had it transpired, it would have constituted one-fifth of all US casualties for the entire war. Eisenhower instead deferred to Stalin, who told him that Berlin was strategically unimportant and that his efforts would be better focused on preventing the Nazis from regrouping in the south. It was advice that Eisenhower was quite happy to take.

Berlin was declared a “defense area” on 1 February 1945. Here, Volkssturm soldiers are instructed how to use a Panzerfaust during the first days of April. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J31391 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Yet neither Stalin nor Churchill was being transparent. It had already been agreed at February’s Yalta Conference that when the Nazi regime toppled, the Allies would divvy up Berlin between them. So why then did it matter to Churchill who took the city first? Similarly, if Berlin was strategically unimportant, why was Stalin so keen for the USSR to single-handedly suffer such high casualties capturing it? After all, he’d spent much of the war prior to D-Day haranguing his allies for not dying enough while Russia was being bled white. Surely now was the time for them to make up for that in this common crusade against fascism?

Militarily it would have made more sense, too – a ready-made pincer movement that would save one side from having to surround the city on its own. The answer to these questions lies in what would appear to be a giant game of chess being played out between Churchill and Stalin, only with real-life pawns and potentially catastrophic consequences on the world stage.

At the start of April, Churchill, fixing his gaze well beyond Hitler’s imminent demise, ordered the drafting of Operation Unthinkable. Documents declassified in 1998 reveal that a month before the end of hostilities in Europe, Churchill was plotting a war against the Soviet Union. In his secret plan, 47 British and US divisions were to launch a surprise attack against the Soviets on 1st July 1945. Moreover, this offensive was to be supported by ten German divisions with the intent not merely of driving the Soviets out of Eastern Europe, but of invading the USSR itself. According to official documents, the aim was to seize “such vast areas of Metropolitan Russia that the war-making capacity of that country would be [rendered] impossible.”

Did Stalin know what Churchill was up to? Almost certainly. By 1945, the Soviets had so successfully infiltrated British intelligence that notorious double agents like Kim Philby and Guy Burgess had been feeding the Kremlin secrets for years. It also explains Stalin’s desire to flood Berlin and its surrounding area with his troops. Control Berlin, as Karl Marx once pointed out, and you control Europe. And if you’re Joseph Stalin, you also put an awful lot of territory between your borders and any newly-drawn battle lines.

Whatever the truth, there’s little doubt that Roosevelt’s sudden death on 12th April prompted Stalin to finally attack. In Roosevelt he’d had an ally he could trust. His replacement, Harry S Truman, offered no such assurances and, rather than wait to be stabbed in the back by those who’d soon be his enemy, Stalin acted decisively. The battle for Berlin began four days later.

In the early hours of 16th April, Soviet propaganda officers announced in German over loud speakers that the assault on Seelow was imminent. The message that drifted across no man’s land was designed to terrorise the Germans waiting there into putting their hands up. But for troops in those trenches and dugouts, surrender was not an option. The SS men who held guns to their backs made sure of that.

Shortly after this, at 3am, 9,000 guns smashed half a million artillery shells into the German line. The bombardment lasted 35 minutes. When it ended, there was a chilling silence. Then the earth began to shake as 3,000 tanks rattled and clanged their way towards the German position, among them tens of thousands of Soviet infantrymen ready for a fight.

The Russians expected to take Seelow Heights within hours, but its German commander General Gotthard Heinrici, had prepared well. Anticipating the bombardment, he’d pulled his troops back for its duration. Casualties had been minimal and they now raced back to their positions. Prior to the assault, he’d also ordered engineers to open a dam on the Oder river, flooding the land the Soviets now struggled to cross as anti-tank fire thundered down on them. The Soviet commander, Marshal Georgy Zhukov, had also made a critical error. Hoping to dazzle the German defenders, he’d lit his men’s advance with 143 high-powered searchlights. His bombardment, however, had created an enormous wall of smoke that their beams couldn’t penetrate and instead bounced back from, blinding his own troops and silhouetting them in the glare. The Germans couldn’t have hoped for better targets to aim at. By dawn the Soviet advance had stalled.

It would take Zhukov three days to dislodge Heinrici’s defenders, and even then only after his great rival Marshal Ivan Konev began to outflank the Germans from the south. The defensive position at Seelow fell on 19th April. About 12,000 of its defenders had been killed and the rest now fled. It had cost the Soviets more than double that and nearly 750 tanks, but there was now nothing left between them and Stalin’s ultimate prize – Berlin.

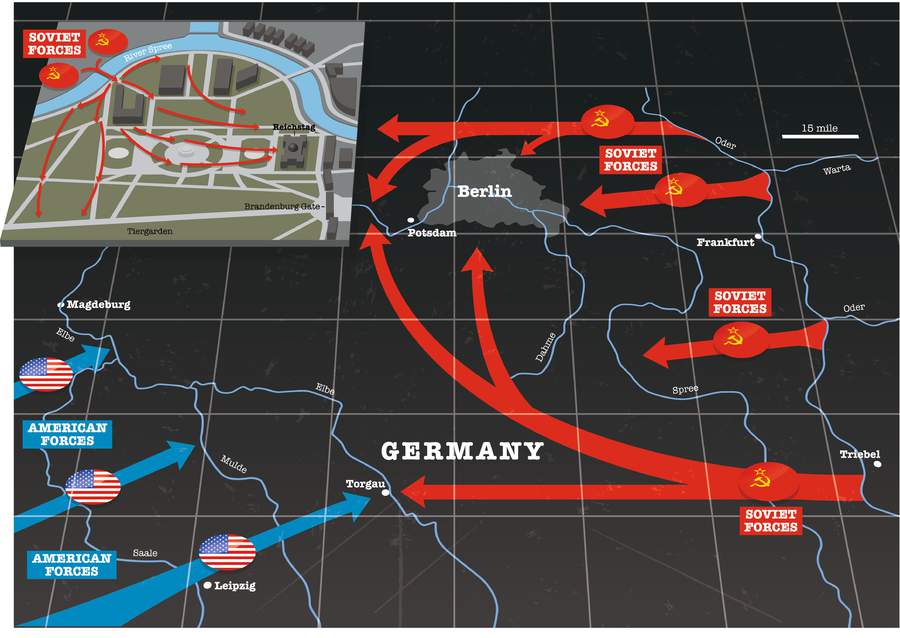

Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front raced towards the city from the east, and by 20th April was on its outskirts. Zhukov marked what was to be Hitler’s final birthday by launching a huge artillery barrage against the city. Cowering in his Führerbunker, Der Fuhrer, by now deranged and deluded, ranted wide-eyed about how the German people had betrayed him. If he was going to die, he shrieked, then they would die with him. The war was lost, and Hitler knew it, but he’d make Berlin’s three million inhabitants suffer terribly. The following day Zhukov’s ground troops began their assault.

To the south, meanwhile, Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front was also making rapid progress. It’d broken into open country and was chasing what was left of the German 9th Army. By now, these German troops, who’d fought so bravely at Seelow, were slowly being encircled. They fled towards Berlin where there was still an opening in the front but, on 24th April, were halted at the town of Halbe. Not by Russians, however, but by SS troops holding the line there.

Mistaking the approaching Germans for a Soviet column, the SS opened up on them. The men from the 9th scurried for cover, and by the time the SS realised their mistake, Konev’s troops were swarming all over them, assaulting the SS defences. The 9th were trapped between the two sides and when fighting eased six days later, 60,000 Germans lay dead, some by the hands of the comrades they were supposed to defend.

The rest of the 1st Ukrainian Front swept forward, driving relentlessly towards Berlin. By nightfall it had made contact with Zhukov’s troops west of the capital. With the 2nd Belorussian Front hemming the city in from the north, Berlin was now surrounded.

Hitler attempted a counter-offensive. He ordered the German 12th Army facing US troops in the west to smash through the Russian lines, link with the beleaguered 9th and drive northward to Berlin. It was a wild gamble that had no chance of success. Halted 32 kilometres (20 miles) from the city, the 12th was soon sent back by overwhelming firepower.

The Russians now tightened the noose, and the siege that would engulf the city for the next two weeks reduced the once splendid capital to the inner circle of hell. The air became poisoned with the stench of burning buildings and rotting flesh, the streets busy with twisted corpses, the cellars and subways filled with untreated wounded. As the food ran out and the water supply dwindled, those in uniform ran amok. The civilian population was terrorised by both the Russians – who hunted in packs for the city’s females, raping whoever they found regardless of age or medical condition – and those supposedly defending them. By now the mask of respectability had slipped from the faces of those who wore the swastika, the Death’s Head or SS lightning bolt badges. The slavering faces of the monsters beneath were revealed as they roamed the city in gangs murdering anyone they deemed cowardly or defeatist. The corpses of old men and children alike swung creaking from the city’s scorched lampposts and trees.

A doomed last stand was prepared. General Helmuth Weidling, the man to whom Hitler had given the impossible task of defending the Nazi capital, established a defensive perimeter around the city centre. His 85,000-strong force, made up of literally the last men (and boys) standing now, faced an onslaught from 500,000 Soviet troops.

In the early hours of 26th April, the final battle began. The streets quaked and crumbled as Soviet armour rumbled through them, while artillery and aircraft rained down fire from above. Every street was contested by infantry, with much of the fighting conducted house-to-house and hand-to-hand.

By 28th April, Tempelhof airport was in Soviet hands. There was now no way out, and the German lines were collapsing fast. The following evening, Soviet troops captured the Moltke Bridge over the River Spree, giving them direct access to the Nazi heart. Within hours they’d captured Gestapo Headquarters. They were now a mere kilometre from the Reichstag and just 700 metres from Hitler’s bunker. The brutal end was, now, inevitable.

Weidling delivered the news to Hitler on the morning of 30th April, also informing him that his garrison only had enough ammunition to last 24 hours. He begged Der Führer to allow him to attempt a breakout, but there was to be no escape. Hitler dismissed Weidling’s request, and later that afternoon blew his own brains out. Whether or not this news would have persuaded the die-hard Nazis defending the Reichstag to surrender is doubtful. What isn’t, though, is that many of the men the Russians exterminated, as they fought their way to the top of the building, weren’t German.

The voices the Russians heard echoing along the burning corridors, in smoke-choked offices and even in the grand auditorium were French, Norwegian, Danish, Dutch and Latvian – members of the SS’s various foreign legions, dying in the German capital while fighting for their twisted ideology. By 10.40pm that night, the swastika had been taken down from the roof of the Reichstag and replaced with the red flag of Soviet communism. The symbol of one defunct political ideology was replaced by that of what would eventually be another. The Battle of Berlin may have helped end World War II, but it also marked the start of a new global conflict, one that would last for the next 45 years and stretch around the world. For it was in the rubble of the Reichstag that the next global ideological conflict –the Cold War – was born.