Taken from Dixe Wills’ new book Tiny Histories, here are ten apparently insignificant events in British history that have had massive repercussions

1. Leopold Lojka makes a wrong turn

Unarguably the most famous and by far the most catastrophic navigational error of all time took place in the city of Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. Following instructions, Leopold Lojka, a chauffeur driving a car carrying Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, turned right along Franz Joseph Street. Urged frantically by a senior official to turn back, Lojka happened to stop in front of Moritz Schiller’s delicatessen, outside which was standing Gavrilo Princip, one of the team of young Bosnian Serb assassins in Sarajevo that day. Princip (who had not just bought a sandwich – that part of the story is an urban myth) stepped forward and fired the shots that would kill Ferdinand and his wife Sophie, propelling the Austro-Hungarian Empire into conflict with Serbia, a state of affairs that quickly escalated into what would become the First World War.

2. A British soldier shows mercy to a future German Chancellor

By contrast, the planet’s other global conflict might have been averted but for a shot that was not fired. The action, or inaction, took place in September 1918 in the French village of Marcoing. The 29-year-old Adolf Hitler unwittingly stumbled into a British soldier’s line of fire. On the point of pulling the trigger, the serviceman realised that the enemy Gefreiter (equivalent to lance-corporal) was wounded and not making any attempt to shoot. Unwilling to kill the man in cold blood, the British soldier lowered his weapon. The future author of Mein Kampf acknowledged the act of clemency and slipped away. For decades afterwards, the gallant infantryman was believed to have been Private Henry Tandey, the most decorated British soldier of the Great War. However, it has since been proved that he and Hitler were not at Marcoing at the same time. As it is, the identity of the soldier who could have shot Hitler will probably never been known.

3. The BBC postpones Steptoe and Son

Perusing the television schedules for the evening of the forthcoming general election in October 1964, Labour Party leader Harold Wilson noticed that at 8pm the BBC was showing an episode of Steptoe and Son, a show that drew up to 20 million viewers. Back in 1964 the polls closed at 9pm and Wilson was afraid that if Labour voters stayed at home to watch the programme it might cost him 20 marginal seats. He called at the home of Sir Hugh Greene, the BBC’s director-general, to discuss the matter. Greene talked to the controller of BBC One and they moved Steptoe and Son to 9pm. Labour duly won 317 seats, the smallest parliamentary majority since 1847. During the subsequent six years of his first premiership, Wilson was socially very liberal, a great contrast to Ted Heath, the defeated Tory Prime Minister. He abolished capital punishment and eased laws on abortion, censorship and homosexuality. Wilson also oversaw legislation that would establish an enduring legacy: the Open University.

4. A pharmacist’s assistant mistakes one cask for another

Back in 1858, sugar was a costly commodity. Unprincipled dealers were wont to bulk up their merchandise by adding ‘daft’, a cheap sugar substitute such as powdered limestone or gypsum. In October that year, a Bradford confectionery stall owner called William Hardaker ordered some peppermint humbugs from one Joseph Neal. One of Neal’s employees went to pick up some gypsum to be used in the sweets from a pharmacy. Since the pharmacist was unwell, he told his assistant where to find the gypsum. Unfortunately, he misunderstood and chose a cask containing arsenic. The effect on the local humbug-sucking populace was devastating. Twenty people – mostly children – perished while around 200 others suffered arsenical poisoning. The ensuing furore played a major rôle in the passing of the Adulteration of Food and Drink Act, followed by the Pharmacy Act, which tightened up the procedures surrounding the issuing of poisons. These laws formed the basis for modern-day legislation that shields us from food and drink that could kill us.

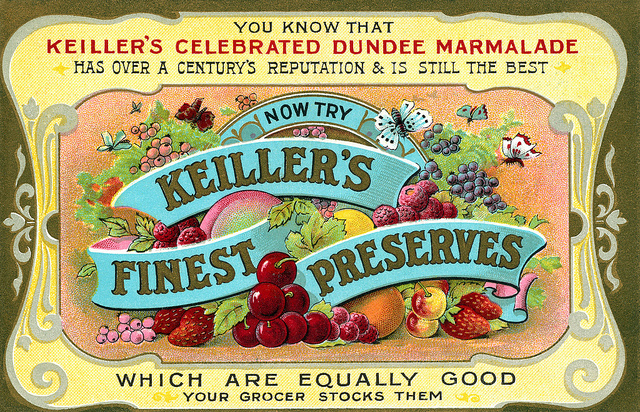

5. A ship containing oranges is battered by a North Sea storm

One day in the 18th century (the precise date is uncertain), a ship carrying Seville oranges from Spain began to make heavy weather of it in a North Sea storm. Although probably bound for Leith, near Edinburgh, the captain put in at Dundee and cut his losses by selling the oranges off cheaply. John Keiller, a local grocer, promptly bought up a good quantity. The Seville orange has a bitter taste and was not likely to sell well so his wife Janet decided to make them into marmalade. She spared herself the wearisome task of pulping the oranges by cutting the peel into chips. Janet’s ‘Dundee Orange Marmalade’ proved immensely popular and, in 1797, the couple’s son set up the firm James Keiller and Son to produce the marmalade on a mass scale. Copycat operations sprang up in Dundee, making it the thick-cut marmalade capital of Britain. Before long it was a staple of the British breakfast, spreading itself across the whole Empire.

6. Three friends take a bet

In 1684, in a London coffee house called The Grecian, three friends had a wager that would change the face of science forever. Edmond Halley, Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke laid money on which of them could set out the mathematics demonstrating why the path of planets around the Sun was elliptical. Halley sought advise from Isaac Newton who claimed he’d already solved the problem. However, he couldn’t find his workings among his papers, so he sat down to write them out again. The scope of Newton’s solution widened dramatically until, eventually, he had delivered Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), a three-volume work of staggering genius. It remains a towering landmark in the scientific landscape, forming the groundwork for revolutions in the realms of physics, mathematics and astronomy. Principia is the basis on which scientists have made myriad discoveries, thus shaping our world today

7. A naturalist turns down an offer from Captain Cook

Edward Jenner was a 23-year-old surgeon when he was asked to join Captain James Cook’s second voyage of discovery in 1772. Along with medicine, natural history was Jenner’s abiding passion, and the voyage might well have made his name. After agonising over his decision, Jenner opted to become a doctor in Berkeley, Gloucestershire. Acting on the rural folklore that dairymaids never caught smallpox, Jenner extracted some pus a cowpox-infected dairy maid and introduced into the arm of an eight-year-old boy. The lad contracted cowpox, recovering after a week. Jenner then exposed him to a small dose of smallpox but he did not come down with the disease. Jenner published a book detailing his findings into ‘vaccination’. The practice became compulsory by law and smallpox was wiped out in Britain. A much more recent vaccination campaign by the World Health Organisation vanquished smallpox globally, making it the only infectious disease ever to have been eradicated by the actions of humans.

8. A cyberspace prank played on Prince Philip before the internet even existed

Almost forgotten now, Prestel was Britain’s very own internet before the internet itself came on the scene. Launched by the Post Office in 1979, users could browse more than 100,000 pages, and use a service called Mailbox, which was very similar to today’s e-mail. In October 1984, journalist Robert Schifreen was testing a modem when he inadvertently hacked into the system. To expose Prestel’s slipshod security, he had a look at Prince Philip’s Mailbox account and then publicised what he had done. After pressure from Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Schifreen and another journalist, Steve Gold, were arrested. Since computer crime legislation didn’t exist, the two were charged using anti-forgery laws. Their case went all the way to the House of Lords, where they were acquitted. The affair exposed the inadequacy of the law and led, eventually, to the Computer Misuse Act of 1990. Although the legislation was far from perfect, it has been used by many other countries as a template for their own computer-crime laws.

9. Four young Germans make a two-minute appearance on television

In 1975, a television segment that lasted just 147 seconds helped shape the music we hear today. It was broadcast on Tomorrow’s World, the future-watching BBC series, and showed the German band Kraftwerk performing the first couple of minutes of their 22-minute song ‘Autobahn’. Presenter Raymond Baxter explained that this was ‘Machine Music: the sounds are created at their laboratory in Düsseldorf, programmed, then recreated on stage…’ The footage suddenly brought the band to the attention of a huge audience and led to the emergence of synthpop artists in the late 70s and early 80s. Other genres followed, all of which owed their roots to Kraftwerk: hip-hop, house, electro, drum and bass, techno, and more or less any other style that involved a synthesiser in some way. Musicians from David Bowie to Joy Division and Franz Ferdinand to Daft Punk have acknowledged Kraftwerk’s influence on their output.

10. A man cannot find anything interesting to read

One day in 1934, Allen Lane found himself at Exeter St David’s railway station looking for a good book to read on the journey back home to London. Unfortunately, the station shop sold only magazines and pulp-fiction paperbacks. His exasperation triggered an epiphany: he would devise a way of publishing inexpensive paperback versions of books that had some literary merit (which were only available then in pricey hardback form). Lane, the Managing Director of publishers The Bodley Head, rounded up his brothers Dick and John and together they founded Penguin Books. On 30 July 1935, they launched ten titles at 6d each. The books were an instant success, sparking a number of copy-cat companies, and the mass-market quality paperback was born. In 1960, Penguin published an unexpurgated version of D.H. Lawrence’s novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover in order to challenge the Obscene Publications Act. A trial ensued, which Lane won. The case is now viewed as a landmark victory for freedom of expression.

Tiny Histories by Dixe Wills is published by Quadrille on the 19th October, priced £16.99. For more landmarks in history, subscribe to All About History for as little as £26.