Anatoli Gubariev was an engineer in one of the fire departments sent to put out the fires raging in the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. He was born in 1960, making him just 26 at the time of the disaster. He had served in the Soviet Army for two years before getting a job at a Kharkov machine-tool factory where he was earning a qualification in metal cutting from Kharkov Polytechnic. Here, he shares his experiences of the disaster with All About History.

On 26 April 1986, a reactor at one of the world’s largest nuclear power plants exploded, unleashing thousands of tons of nuclear waste into the air. The fire in Reactor Four in Chernobyl power plant burned for nine days following the accident. Very few, if any, were told the true scale of the task that was ahead of them. One such man was Anatoli Gubariev, a 26-year-old plant engineer in the fire battalion.

“It was 4 May and I had just returned home. Opening the door I saw a man holding a folder. He asked me ‘You are Gubariev?’ I said I was and he said ‘Receive and sign it!’ It said ‘Writ Command. In an hour you must show up at this meeting point.’ It was in the Palace of Pioneers Ordzhonikidze district of Kharkiv”, says Gubariev.

Firefighters, helicopter pilots and medical staff came from all over the country to help with the rescue effort. What angered people later was how little information was made available by the Soviet government (Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union until 1989) and their attempts to cover up the truth.

“I had no idea about the scale of the disaster. I had read a short notice on the third page of Komsomolskaya Pravda [A daily Soviet tabloid] on 29 April and that was it. I was later able to learn more about it from the news of forbidden Western sources such as Voice of America and Free Europe, which sometimes broke through.” Gubariev recalls that as they assembled to go to the plant to help with the containment operation, “There were about ten buses at the meeting point. Someone tried to make a joke but it didn’t get much support. It was at this point that we realised this was not a game and something very serious was going on.

“Over the next five days they created teams capable of combating fire. Everyone became accustomed to the fact we had to go to Chernobyl. We plunged into new buses and drove off. The column seemed to be endless. We were headed by a police escort car, then our coaches and finally the special firefighting trucks. Two things stick out in my memory from that journey. The first was wells covered in plastic wrapping and the second was a young family of husband, wife and a two-year-old daughter trying to escape the horror of the contaminated area on an old moped.”

The two closest towns to the nuclear power plant were Pripyat and Chernobyl, which had about 68,000 residents in total. It wasn’t until 36 hours after the accident that the authorities begin evacuating people. In total, 130,000 were moved as the evacuation zone increased to 30 kilometres (18 miles). Teams worked around the clock to secure the area, including helicopter pilots who were spraying a mixture of sand, lead and boron onto the reactor.

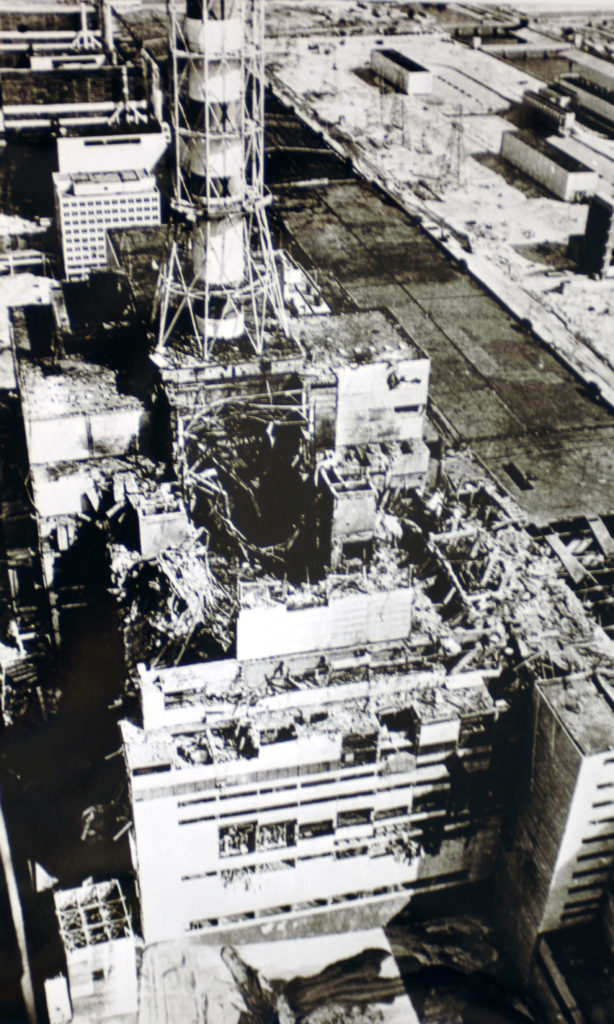

“Everyone who was already at Chernobyl were wearing strange clothes,” explains Gubariev. “Some were wearing white jackets and trousers, some in blue. People were reacting differently to what was happening. Some with caution, some with undisguised dismay and some with bravado. I could now see the ruined concrete structure of Reactor Four and the faint steam cloud that was rising above it. That steam cloud stayed above the reactor until 20 May. We drove up to the reactor and stopped about 100 metres (330 feet) away. From there, we could get to the site using an infantry fighting vehicle, or we would have to run through the administrative building.”

By this point in proceedings Moscow was well aware of the scale of the tragedy and how bad the nuclear fallout really was. However, they continued to pour workers into the area in an attempt to bringing the disaster to an end as soon as possible, regardless of the health risks to those tasked with bringing normality back to the plant. Keen not to lose face to the western world during the Cold War, there was a heavy blanket of secrecy over the whole event.

“Our battalion’s duty was to carry out fire protection within a 30-kilometre (18-mile) radius and in the power plant. We had to extinguish fires in this territory. Around 3:15 on 19 May we heard the call ‘Battalion! Alert! Ready in one minute!’ After a few minutes I was driving in a column of fire engines from our site to the Chernobyl power plant,” Gubariev says. “There was a rectangular container filled with iodine that you had to dip your boots into and a young soldier with a gun sitting at a checkpoint, obviously scared and not understanding what was happening.

“We started to carry out our task. The first people went and after 30 minutes they took a few more. Then it was quiet and we spent over an hour waiting. Then we were told to take two sleeves and run.” This command meant that Gubariev and the rest of his team had to take two fire sleeves and run with them in the direction of the heart of the fire. “I rushed to the car, grabbed them and ran. We were already dressed up in chemical protection suits, which were rubber overalls that didn’t let any air or moisture in, and face respirator masks,” he recalls. “The major, sergeant and dosimetrist (doctor specialising in radiation) told us that where we were, the radiation level was two X-rays an hour. Just outside the door it was 60 X-rays an hour. The further in, the more radiation there was. We were to keep our respirators on. It was very difficult to do that in such conditions as sweat was running all over our faces and we felt the lack of air. We had to lay the sleeves along the corridor so water could flow through it. To do this we had to find the ends of the previously laid sleeves, connect ours and run back. As people came back through the door, they fell out totally wet and exhausted.”

It’s hardly surprising that Gubariev and his troops were sweating. Temperatures inside the reactor’s core had reached an incredible 2,000 degrees Celsius (3,632 degrees Fahrenheit), which is over two times as hot as lava. The graphite moderator, which is used to slow down electrons so they can release more fission, had exploded violently and was not only continuing to burn fiercely in the reactor, but had also flown all over the plant. This was because the reactor had malfunctioned and was releasing nuclear waste into the air.

“This was the point of no return. Water squelched under my foot and the corridor seemed infinitely long. From time to time I came across burning bulbs, which were landmarks,” he says. “Finally, I reached the stairs. On I ran, even faster. I felt caught in a long corridor with almost no light and, as we thought, no end. Finally, I noticed a beam of light from the lantern standing on the floor. We joined up the sleeves and moved the lantern on, trying to illuminate the space in front, but we couldn’t see a thing in the smoky darkness. The only noise was the rushing of water. When I was coming back, it seemed that the corridor became three times as long and the arms of the protective suit seemed to be as heavy as tons of stone. How I got out of there I do not remember but the main thing was, we were safe.”

Once out, the workers were instantly checked by the dosimetrists to see how much radiation they had absorbed. Gubariev had only absorbed seven X-rays of radiation, but his fellow worker, Nick, had received a dose of 20 X-rays. To put this in perspective, the average amount of radiation a person would generally expect to receive in an entire year is just 3.1 X-rays. They increase the risk of cancer by releasing electrons from atoms inside your body, which damage DNA. Many workers at Chernobyl received huge amounts of this radiation, leading to health problems later in life.

“Cleaning workers on the power plant showed the best human qualities such as selflessness, heroism, self-sacrifice, sense of duty and mutual assistance. There was nothing special or heroic about what we had done. It was hard work and we were risking our lives, but we were all just doing a job.”

Gubariev might have only thought he was ‘just doing a job’ but the Soviets disagreed, honouring him with the highest peace-time award possible, a first-class government medal for ‘Distinction in Military Service.’ He was there for 35 days in total, working shifts ranging from two to 14 hours. It was not until afterward that he learned exactly how much danger he and the rest of the people working there were in.

“I will never forget the young family that was trying to escape on their old moped, to escape the horrors of Chernobyl”, he recalls. “A woman with a baby wrapped in wax cloth. Her husband in his shirt sleeves. On the back of the bike, a plastic bag with all their belongings, all they managed to take with them to enter their new life.” More than 30 people died in the weeks following the explosion and hundreds of thousands more have suffered with radiation-related illnesses such as thyroid cancer, but if it were not for those brave souls like Anatoli Gubariev who risked their lives to battle the terrifying inferno of Chernobyl, it could have been much worse.

This Article originally appeared in All About History issue 17. Save money on the cover price by Subscribing Today