In recent weeks, images of molten lava spewing from Hawaii’s Mount Kilauea have left the world shocked and awed. The ongoing eruption has destroyed more than 650 homes and forced 2,000 people to evacuate since it began on 3 May. The volcanic blast is even reshaping the landscape, with the lava completely filling the picturesque Kapoho Bay, adding 555 acres of land to Hawaii’s Big Island, according to the US Geological Survey.

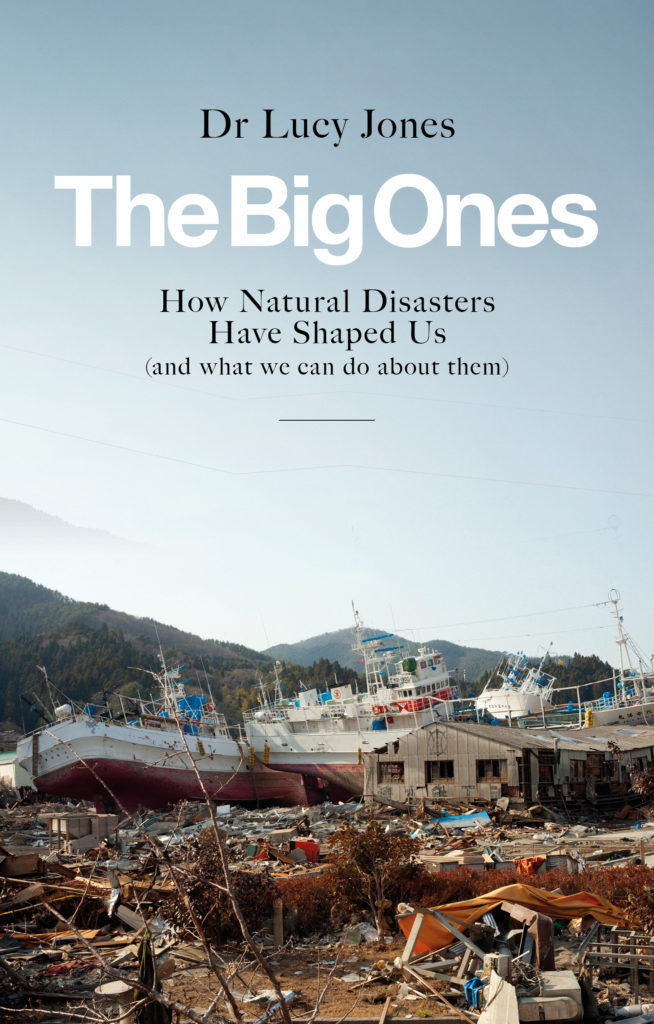

World-renowned seismologist Dr Lucy Jones argues that natural disasters can also reshape history in her new book, The Big Ones. From Pompeii to Hurricane Katrina, it covers 11 disasters in-depth, exploring the historical context leading up to the event, the carnage it caused, and its lasting impact, plus what might happen to Jones’ hometown of Los Angeles when the San Andreas Fault inevitably cracks. We caught up with Dr Jones to learn more.

What made you decide to want to write The Big Ones and, in particular, why now?

I spent my life studying disasters and came to see how much the scientists know about what will happen in future events that is not being used the public, by decision makers, by policymakers, to help us all be safer and more resilient to these disasters. When I retired from my government service, I finally had time to flesh out these ideas. I want to help people see that although the natural hazards are inevitable, the disasters are not and we have choices we can make to protect ourselves.

The destruction of Pompeii still grips our imagination as an event of near-apocalyptic proportions. How significant was the eruption really in terms of its scale compared to other disasters?

Scale is a difficult term. In geologic terms, this eruption was 6 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI). The highest possible is 8, but none that large has happened in historic time. The eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 was a 7, as was the Santorini eruption in prehistoric times, both of which blew apart their mountains. So, on the geologic scale, Pompeii is very big but not the biggest of historic times. In human terms, the complete destruction of several populous towns is noticeable, but is not as significant, say, as the 1556 earthquake in Shaanxi, China that killed 850,000 people. Pompeii grips our imagination because we don’t need to use our imagination. All the victims are there for us to see.

Much is made of the Year Without Summer following the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora, which it’s been argued led to the invention of everything from Gothic literature to the bicycle. How much stock do you put in these claims?

The eruption of Mount Tambora is one of the largest eruptions ever recorded, and it had a major impact on the earth’s climate. The cooling of the earth was very real. The effect dies off after a few years as the material pushed into the atmosphere that is blocking incoming sunlight is gradually washed out by rain. The human impact is much less amenable to definitive statements of cause and effect. Did the famine caused by the Lake eruption in 1784 really contribute to the French Revolution? Did the destruction of Tokyo in the Kanto earthquake of 1923 really lead to the rise of the militarist faction in Japan? Did the Tangshan earthquake in 1976 lead to the downfall of the Gang of Four? Did the response to Hurricane Katrina really lead to the Republican loss of control of Congress in 2006 and Obama’s election in 2008? They are all probably factors but we can’t conduct an experiment to determine what would have happened if the eruptions or earthquake had not occurred.

How did you choose the 11 disasters that you feature in The Big Ones?

My criteria for inclusion were: The event was a Big One for its culture – an event that made fundamental changes to society, and I had some idea that I wanted to explore with that story, and I had some insight to provide about the event. So for instance, the 1994 Northridge earthquake was not included because it wasn’t really a Big One. The 1906 earthquake in San Francisco is not included because I didn’t think I had anything to add to what has already been written about it.

As a seismologist living in LA – and on the San Andreas fault line – how do you live with the knowledge that you are living on a geological time bomb?

I am a fourth generate Angeleno and I would not want to live anywhere else. But just about every major city in the world has some disaster that will happen to it at some point. We build our cities in geologically hazardous places, because they have other advantages. We build on coastlines because they bring shipping – and hurricanes. We build near rivers for water – and get floods. We build near faults that create good harbors and oil fields – and bring us earthquakes.

I live here because I know that 1) ‘being overdue’ usually doesn’t mean anything other than a journalist desperate to find a pattern. The timing is quite random and I will probably not live to see these things, and 2) most damage is preventable with planning and therefore rather than move, I am focused on helping my policymakers make better choices. Many other people live here relying on our normalization bias, the very human belief that the worst that has happened to me is the worst that can happen.

The Big Ones: How Natural Disasters Have Shaped Us (And What We Can Do About Them) is available now for £12.99 from Icon Books.