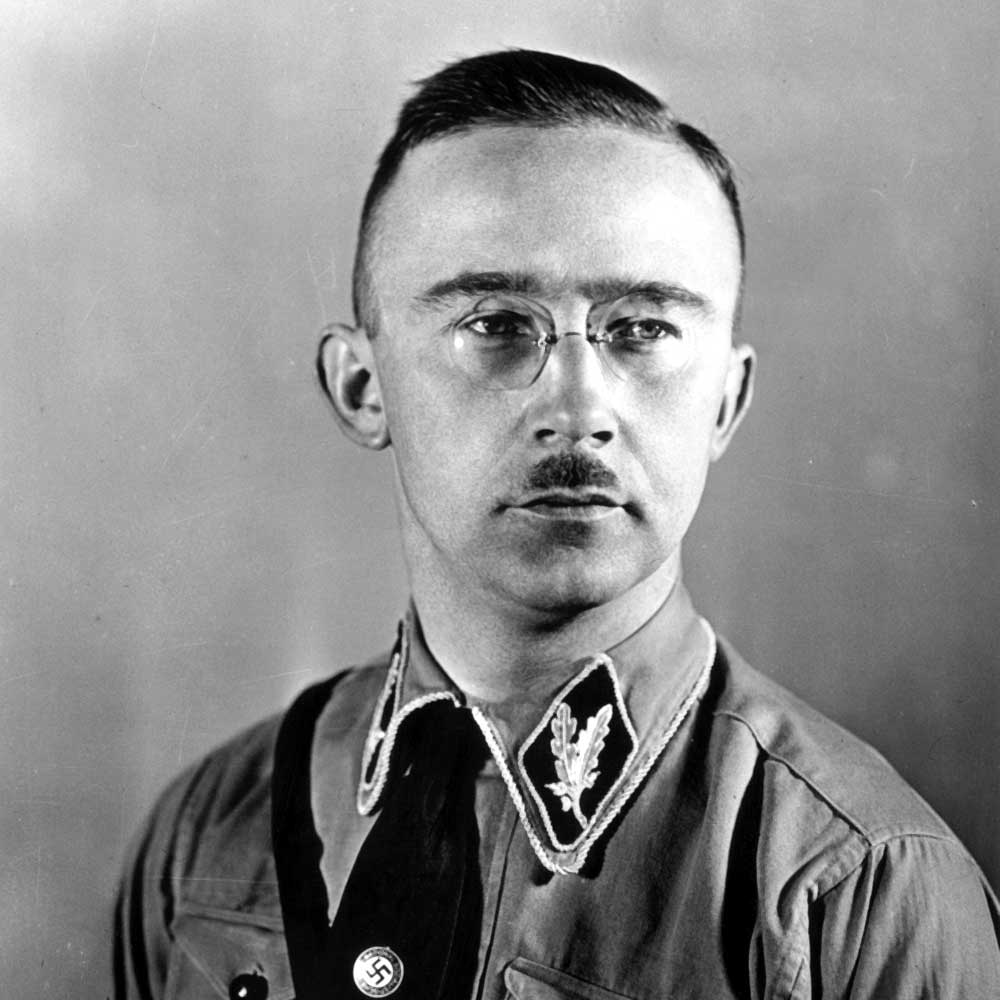

From a young age, Heinrich Himmler – the future Reichsführer SS and chief of the German police – nursed a fascination with legends of the distant past. Himmler’s father, Gebhard, an eccentric school teacher with strong nationalist leanings, often read aloud to his sons in the evenings – introducing young Heinrich to the Nibelungenlied, the medieval tale of Siegfried, and the Edda, a collection of ancient Norse sagas. Both inspirations for Richard Wagner’s epic Ring Cycle.

Despite the family’s modest middle class standing, an entire room of Himmler’s childhood home in Munich was dedicated to Gebhard’s conjured perception of the family’s distinguished heritage – an Ahnenzimmer (ancestor room).

As Der treue Heinrich (loyal Heinrich) later rose through the ranks of the Nazi party, his seniority would grant him the opportunity to turn his inherited passion for myth into a state enterprise. In 1935, he founded the Ahnenerbe (‘inheritance from our ancestors’), an institute for archeological and cultural research that sought to lend credence to some of the Nazis worst racial theories. The organisation acquired a luxurious Berlin mansion house on Pücklerstrasse, in the quiet neighbourhood of Dahlem, for its headquarters, just a few blocks away from where Himmler himself lived.

Ambitious expeditions to Sweden, Finland, and as far away as Iraq and Tibet were organised, with these assignments sometimes jointly serving as military intelligence gathering opportunities.

The Ahnenerbe recruited an assortment of scholars, scientists, archaeologists, historians, doctors and researchers – all awarded honorary SS titles.

Ancestral research became an exclusively political endeavour, where the trophies of these expeditions were expected to serve as the title deeds of the nation and a measure of the people’s spiritual currency. Misusing science and scholarship for political ends became the status quo, as Himmler increasingly sought to pervert the past to justify his persecution of the living.

Not only did the organisation attempt to document the racial heritage of the Germanic people but also illustrate the group’s perceived supremacy. Special effort was made to identify the origins and classify the characteristics of designated foreign threats. Researchers endeavoured to produce an index system to help identify, isolate, and eventually annihilate, the inferior jewish race. Undertaking Rassenkunde studies (racial research projects) in the form of increasingly grotesque and sadistic medical experiments that would lead to one of the most notorious war crimes of the period – the procurement of a Jewish skeleton collection.

Expected to independently raise capital for its expeditions and research, the Ahnenerbe was plagued by chronic funding issues from its inception. Himmler, however, ultimately devised a plan that would see the entire country helping foot the bill for his pet project.

One of Hitler’s former drivers, a part-time inventor and loyal party comrade, had started producing bicycle reflectors, to improve the visibility of riders on the roads at night. Fastening small pieces of glass to bicycle pedals that would reflect the headlights of oncoming cars. In 1936, the SS formed a joint-company with the inventor, using his name – Anton Loibl GmbH. With SS help, Loibl applied for and promptly received a patent for his bicycle reflector design. A rival inventor even had his earlier patent application quashed.

In his capacity as police chief of the Reich, Himmler then issued a new ordinance on road traffic that made the reflectors mandatory for all bicycles on German roads. The SS company would oversee the marketing of Loibl’s invention and use part of the revenue to fuel Himmler’s research projects.

Industrial producers had no choice but to pay licensing fees back to the company for the privilege of producing Loibl’s design and within the first year the Ahnenerbe received 77,740 Reichmarks from the scheme. From 1939, this would rise to between 100,000 and 150,000 Reichmarks per year. As much as financial integrity was expected from members of the SS in their personal lives, the procurement of funds through questionable, and often illegal, means was actively encouraged when it was a matter of financing the organisation.

Although the activities of the Ahnenerbe came to an abrupt end in 1945 – the section of the traffic order which relates to reflectors, introduced by Himmler, is still part of Germany’s street law for bicycles – the Straßenverkehrszulassungsordnung. Along with two sets of functioning brakes and lights for travelling at night, all riders are required to display two yellow reflectors on each wheel – pedal reflectors – one white reflector on the front of the bike and one red reflector on the rear.

With the notable exception of Ahnenerbe head, Wolfram Sievers, who was convicted of crimes against humanity and executed in 1947, and Himmler himself, who committed suicide in British custody in 1945, most of the individuals involved in the organisation’s work – in particular the researchers and scientists – continued to practice in their chosen fields following the end of the war. Often hiding in plain sight.

Matthew Robinson is a founder and tour guide with Berlin Experiences. For more on the darkest moments in 20th century history, pick up the new issue of All About History or subscribe now and save 25% off the cover price.

References:

- Evans, Richard (2006). The Third Reich in Power.

- Hale, Christopher (2009). Himmler’s Crusade: The Nazi Expedition to Find the Origins of the Aryan Race

- Longerich, Peter (2012). Heinrich Himmler: A Life.

- Neumann, Franz (1944). Behemoth. The structure and practice of National Socialism.

- Pringle, Heather (2006). The Master Plan: Himmler’s Scholars and the Holocaust.

- Reitlinger, Gerald (1953). The Final Solution.

- Speer, Albert (1970). Inside the Third Reich

- Stiftung Topographie des Terrors (2010). Topography of Terror: Gestapo, SS and Reich Security Main Office on Wilhelm- and Prinz-Albrecht-Straße. A Documentation.