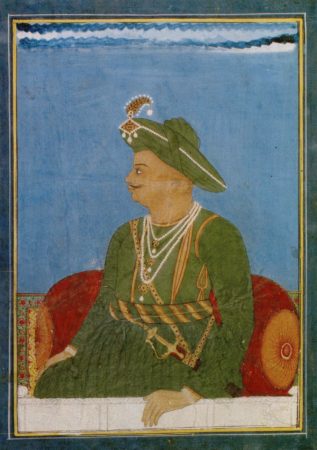

No one in the 18th century made the hearts of the English ‘lions’ quake with fear as much as Tipu Sultan, known as the Tiger of Mysore. So safe and just was his reign, his court poets tell us: “the deer of the forest make their pillow of the lion and tiger, and their mattress of the leopard and panther.”

These words aren’t just platitudes heaped on the Mysore ruler; they speak of a reign that forever changed the fortunes of the Indian subcontinent. There is no doubt that both Tipu Sultan and his father, Haider Ali, “brought the [British] East Indian Company nearer to ruin than any other Indian foes had brought it.”

For nearly 40 years, they halted the triumphant march of the British through southern India, refusing to make their peace with these foreign invaders, as most other powers did. This refusal to submit or compromise saw Tipu Sultan die on the battlefield in 1799, as he fought the British. Even to this day, Tipu Sultan remains a controversial figure in Indian history. Clashing interpretations of contemporary accounts have produced a figure hailed as both a national hero and a brutal tyrant.

He is seen as a restless moderniser, someone who worked to bring his kingdom into the future and resist foreign encroachment. In contrast, he has also been vilified for more than 200 years as a religious bigot who brutalised and forcibly converted Hindus and Christians under his rule. Monarch of the southern Indian state of Mysore from 1782 to 1799, he relentlessly opposed British expansionism in India to first get hailed as a patriot, only to be later denounced as a tyrant.

A master military strategist is eclipsed by the doubts cast on his myriad economic and social experiments. Ironically, there is plenty of archival materials on this historical figure, produced by enemies, friends, victims, captives, perpetrators of conquest, employees and hagiographers, topped off by the copious writings by the sultan himself.

Despite this, it seems early colonial accounts, produced by the British, are responsible for driving the popular image of Tipu Sultan as a tyrant. Demonised by some, championed by others, Tipu Sultan remains a towering figure in Indian history.

‘Tiger, Tiger, Burning Bright’

Tipu Sultan was the son of a talented soldier, Haider Ali Khan, who wrested control of Mysore from the Dalwais, or Commanders-in-Chief, who themselves had already usurped all effective power from the previous Wodeyar king, Chikka Krishna Raj XI.

Haider Ali subjugated the petty local chieftains and grew Mysore into a powerhouse within the Indian peninsula. During the First and Second Anglo-Mysore Wars, Haider Ali had brought the British to their knees. Tipu would come to inherit a formidable burden: his father died during the Second Mysore War that he successfully concluded, but two more wars with the British followed in the Third and Fourth Anglo-Mysore Wars, as well as myriad battles with hostile neighbours on all sides, notably the Marathas to the north west, and the kingdom of Hyderabad to the north east.

In 1792, at the end of the Third War, Tipu was corralled into ceding nearly half of his territory to the British and its Indian allies; was placed under a crippling debt; and gave two sons as hostages to the British until the debt was paid. He was defeated and killed only in the Siege of Seringapatam on 4 May 1799. With their most formidable foe vanquished, the British lion had regained its honour, which neither the British people nor the Indians were allowed to forget. In the days following Tipu’s defeat, British soldiers looted an estimated £1,600,000 of ‘prize money‘, consisting of coins, jewels, richly worked cloth, furniture and carpets.

These were distributed to the rank-and-file and colonels alike. After the plunder, the British feared the sultan’s possessions might become powerful symbols of martyrdom, so Arthur Wellesley intervened to prevent the auctioning of Tipu’s extensive wardrobe to stop them falling into the hands of the “discontented Moormen of this place.”

The ‘Mysore Family‘, as Tipu’s descendents were called, were dispatched first to Vellore Fort and then distant Calcutta. Soon after, a medal was issued in honour of that victory, depicting the British lion mauling the Mysore tiger. It is no surprise that the British were so quick to rewrite the life and times of this implacable enemy.

Modernise or perish

As well as a fierce military ruler, Tipu Sultan also oversaw many economic and administrative experiments. Most of Mysore’s revenues came from the cultivation of the local land, so the sultan’s first priority was to ensure that a good proportion of the revenues due from land were actually collected.

The state coffers would need to be well stocked to keep his vast army, some 100,000 men, at its height, ready for engagement. Lands were divided according to their yield, and taxed accordingly. There were graded taxes for cash crops like sugarcane, and wet or irrigated lands were taxed at four times the rate for dry or rain-fed lands.

He was keen to encourage the cultivation of cash crops like betel nuts (a tasty snack) and sandalwood, known for its fragrance. He imported silk worms from Bengal and Muscat to begin what would become famous as Mysore silk. He maintained and enlarged local breeds of cattle under the amrit mahal, or sultan’s cattle department, unique to Southern India.

The restless monarch was not content with regulating and improving his agrarian economy, and wanted to modernise some of its other sectors fast. At this time, India did not have a well-developed and ruthless merchant class that Britain and other colonial powers possessed, so Tipu Sultan saw the need for the state to step up and fill that void. He encouraged the establishment of state-run factories at Bangalore and Seringapatam, Bednore and Chitaldurg, Chennapatna and Chickballapur, for the production of everything from cotton and silk cloth to cannons and sugar, from paper and glass to guns and muskets.

Despite these innovations, Mysore’s enemy, the British, still possessed superior industry and technology. Eager to level the playing field, the sultan turned to another western power: France. Tipu had a long- standing alliance with the French and employed European workmen in his factories and establishments.

In addition to his ports and currency mints, and his efforts to introduce a banking corporation that included some welfarist measures, he recognised the importance of diplomatic and commercial contacts with Turkey and France, to which he sent embassies. For Tipu, the state was “the chief merchant of his dominions.”

30 factories were established in Mysore, and 17 elsewhere. He instituted a state monopoly of precious commodities, such as sandalwood, pepper, cardamom, elephants and timber. Once the sultan had fallen, the British thought it fit to continue most of these monopolies.

Tipu, a man before his time, realised that without enormous economic reorganisation, he could neither run his war machine, nor ensure the tranquillity and prosperity of his people. And despite his indifferently successful experiments, this is what Edward Moor wrote in his A Narrative of the Operations of Captain Little’s Detachment:

“When a person travelling through a strange country finds it well cultivated, populous with industrious inhabitants, cities newly founded, commerce extending, towns increasing and everything flourishing so as to indicate happiness, he will naturally conclude it to be under a form of government congenial to the minds of the people. This is a picture of Tippoo’s country, and this our conclusion respecting its government.”

An absolute ruler

In the 18th century, the Mughal Empire was already in terminal decline, and the rise of successor states showed that those with energy, will and ambition could carve out new, independent territories. Haider and Tipu rose from nondescript social origins to head a powerful state through the exercise of extraordinary military, political and administrative acumen.

If Haider only undermined the ‘legitimate‘ authority of the Mysore Wodeyar or King, Tipu finally reduced him to a non-entity. Rather than depend on the creation of an aristocracy, local or foreign, in imitation not only of the Mughals but also of the lesser powers of the Deccan who scorned their lowly origins of the Mysore rulers, Tipu developed the framework of a bureaucratic state.

State functionaries performed the task of governance in a more decentralised way, from Patels and Shanbogues to Amils and Asophs, from village level leaders to district level heads. Tipu was certainly an absolutist ruler. He strove to change and alter not just the economy and administration, but also the habits and culture of those who came under his rule in Mysore and beyond.

The folk ballads of Mysore, or ‘lavanies’, remember the man for his many prohibitions that intended to produce a more ‘civilised’ people. Tobacco and liquor were prohibited in Mysore, and attempts made to ban prostitution and trafficking.

Tipu sought to bring temples, mosques, chattrams (feeding houses) and dargahs (tombs of saints) under a new bureaucratic regime to reduce corruption and mismanagement, but also to garner resources for his war economy. Shocked by the polyandry that was practiced in Coorg, and the bare-breastedness of the people of Malabar, both regions over which he won control, he ordered that these practices be stopped and the women be covered. And in addition to introducing new weights and measures, Tipu Sultan inaugurated his rule in 1784 with a completely new calendar.

Pious Muslim, Jihadi or tyrant?

Tipu, himself named after Sufi saint Tipu Mastan Auliya, to whom his parents prayed for a son and heir, was an observant Sunni Muslim. That said, both his political strengths and vulnerabilities led him to make public pronouncements seen as contradictory.

He referred to the British as ‘infidels’ and ‘faithless Christians’ who did not stoop to treachery and collusion to make their territorial gains. In contrast, he was more circumspect and respectful of the French, his allies. He did not hesitate to refer to the Nizam of Hyderabad, a fellow Muslim who deserted him in his hour of need to align with the British, as Hajjam, a derisory reference to his caste. Of the Marathas, who also sided with the British, his choice of insult was not religious so much as questioning their prized masculinity.

Tipu began to acquire his notorious label as a tyrant early in his encounters with the British. According to historian Michael Soracoe, in early 1784, an “anonymous officer” in the East India Company’s service wrote in the English press:

“Tippoo Saib is far from the character he has been represented to us; instead of being a friend to peace, he had proved himself a restless, treacherous, inhuman tyrant. He is entirely influenced by French politics, and has four battalions of Dutch, Portuguese, and French in his service… his army is well appointed, and more formidable than that of his father Haider Ali.”

Tipu was increasingly vilified for his actions against certain communities in his newly conquered dominions, notably the Catholics of Canara, the Coorgs, and the Nairs of Malabar – all of whom he identified as treacherous betrayers, before giving orders for conversion.

This was not a uniform policy however, which makes Tipu the enigma that he is. Accounts of Tipu’s tyranny include destruction of temples, massacres of Brahmins, and conversion and castrations of different castes, as well as the dislocation of large numbers of people to different parts of his domain.

Though these are exaggerated memories, there is a kernel of truth that has been admitted by even his warmest biographers. Yet the governor general of India, Sir John Shore, reluctantly noted in his minute of 18 February 1795: “during the [British] contest with [Tipu], no person of character, rank or influence, in his hereditary dominions, deserted his cause.”

If the sultan was as bloodthirsty as in popular memory, would he have been able to hold the loyalty among both Hindu and Muslim officers? The evidence on temple destruction is not robust either, since there is evidence of Tipu’s conspicuous support of and benevolence towards the most important Hindu temple complexes, such as Sringeri and Nanjangud.

In letters still preserved at Sringeri, the site of Mysore’s most important temple and Brahmin monastery, the Marathas (of Hindu affiliation)

“raided Sringeri, killed and wounded many people there, including many Brahmins, plundered the monastery of all its valuable property, and committed the sacrilege of displaced the sacred image of the goddess Sarada.”

Tipu Sultan showed no hesitation in communicating his concern to the Jagadguru, the chief abbott of Sringeri, calling for the re-consecration of the ’holy place’. He requested that some specific ceremonies be performed, for which he received a share of consecrated offerings to the Gods, called prasada, and in turn made presents to both deity and Swami.

Throughout his 17-year reign, Tipu Sultan’s own allegiance to Islam was not unwavering. Since his father was a ‘usurper’, and his own origins therefore less than regal, he sought legitimacy in a number of ways, by having the Friday khutba (sermon) read in his name, and minting coins at his five royal mints that, by omission, rejected even the nominal superiority of the Mughal Emperor.

Then, giving up the name of Haideri Sarkar for his government, Tipu adopted the title of Badshah of the Sultanat I Khudadad (God-given government) in 1787. In short, he was answerable to no one but God for his actions. However, Tipu understood that he was a Muslim king of a predominantly Hindu domain, and many of his more severe actions were tempered by his recognition of the need to retain his legitimacy.

Tipu’s fortunes were waning by the late 1780s as the forces of the Marathas and the Nizam moved to the British camp, while French support was becoming less and less reliable. The governor general at the time, Lord Cornwallis, had the armies of Calcutta, Madras and Bombay at his command, and recognised Tipu as a “prince of uncommon ability and of boundless ambition” who threatened Company possessions in India; he felt compelled to curb him.

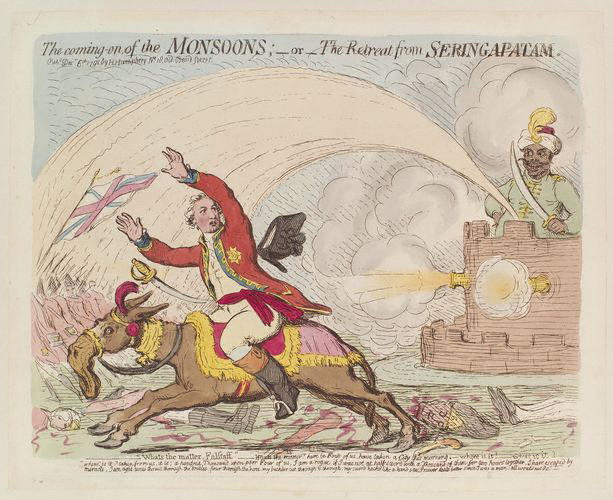

An initial – and ignominious – setback in 1791 at Seringapatam was memorialised in James Gillray’s cartoon. Cornwallis pressed a harsh treaty on Tipu following the Third Anglo-Mysore War, but it was his successor, Richard Wellesley, who was determined to end the house of Mysore, and isolated Tipu before organising his defeat.

The breach and storming of the island fort of Seringapatam, which had long withstood enemy attacks, was enabled in part by the treachery of Tipu’s own men. Even at this penultimate hour, the British underestimated the warrior who had determined to die fighting. When the fort was taken, troops combed the palace for the ‘Tiger’, and found him under a heap of corpses, sword still in his hand.

The British domination of southern India was now complete. In order to scrub the place of any trace of this fallen hero, and to prevent discontents from grouping around the memory of a valiant Tipu, the East Indian Company decided to revive a dynasty that had long been forgotten, the Wodeyars, and also shift the capital from Seringapatam to Mysore.

The island capital soon became a pilgrimage site for British soldiers to relive their victory. Two of Tipu’s palaces were then dismantled; only one summer palace and his mausoleum were allowed to remain. Tipu Sultan Mohammad Iqbal, the noted Urdu poet, who meditated at Tipu Sultan’s tomb in 1929, later wrote:

I have lighted a different fire in the heart.

I have brought a tale from the Deccan…

There I heard from his holy grave;

If one cannot live a manly life in this world

Then to sacrifice life, like a man, is life!

This article originally appeared in All About History issue 52. For more stories that take a fresh look at history, subscribe to All About History for as little as £2.15 per issue!