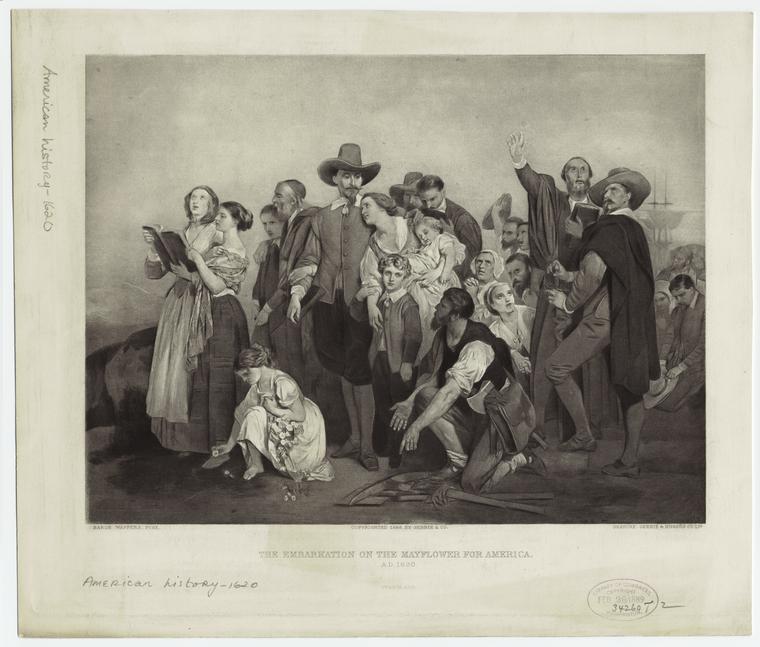

For the first century of the Plymouth colony’s existence, the voyage of the Mayflower was scarcely spoken of outside of its own stockade.

The Puritan Separatists of 1620 may have founded the second English settlement in North America, but it was by far the poorest and Plymouth struggle to survive on its own terms led to it being absorbed by its neighbour Massachusetts Bay, founded 1630.

The history of colonial American gave short shrift to the Mayflower, the Speedwell, the Separatists and the Strangers – these were local, rather than national concerns.

The Mayflower Compact – the charter the Pilgrims signed to bind themselves together in association under the regime of an elected governor – wasn’t remarkable, unusual or interesting in itself. All colonies came with charters.

Only with the dawning of the American Revolution (1765-1783) was the Mayflower Compact reconsidered. Suddenly the narrative of men and women coming to America – to escape the (religious) authority of the king, no less – and choosing to band together, choosing their leader and laws, and choosing where they settled became incredible relevant.

Alongside England’s Medieval Magna Carta, the Mayflower Compact’s “such just and equal laws […] as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good,” provided precedent of the supremacy of common law over executive authority that underscored the Bill of Rights

Purely in terms of perception, it was certainly preferable to honour Plymouth and the Pilgrims over Virginia and Jamestown – planted by royal warrant and named in honour of Elizabeth I and James I respectively.

The precedence of the Plymouth colony over the Virginia colony would prove useful too in pushing the role of slavery from the central narrative. It was politically expedient to sidestep the hypocrisy implicit in the Constitution with the declaration that “all men are created equal” by arguing that America began not with the plantations of Jamestown, but the arrival of the Pilgrims.

Opponents to the American Revolution, meanwhile, were quick to point out that the Mayflower Compact was also a statement of fealty to the crown, beginning as it does:

“We, whose names are underwritten, the Loyal Subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith…”

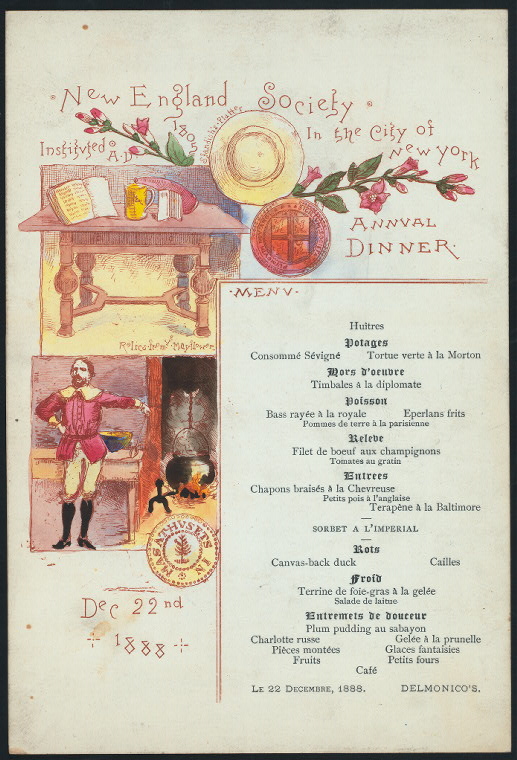

Observance of the Mayflower settlers and particularly that Plymouth institution, Forefather’s Day, quickly spread to Boston in the late 18th century to become part of the culture of New England, and by the early 19th century was being trumpeted by elected officials as evidence of New England’s exceptionalism, proud traditions of liberty, and heritage as the cradle of the nation.

The Missouri-born critic Mark Twain pilloried the regional fixation in an 1880 speech to the New England Sons in Philadelphia:

“Your ancestors broke forever the chains of political slavery, and gave the vote to every man in this wide land, excluding none! None except those who did not belong to the orthodox church. […] Hear me, I beseech you; get up an auction and sell Plymouth Rock! The Pilgrims were a simple and ignorant race; they had never seen any good rocks before, or at least any that were not watched, and so they were excusable for hopping ashore in frantic delight and clapping an iron fence around this one; but you, gentlemen, are educated; you are enlightened; you know that in the rich land of your nativity, opulent New England, overflowing with rocks, this one isn’t worth, at the outside, more than 35 cents. Therefore, sell it, before it is injured by exposure, or at least throw it open to the patent medicine advertisements, and let it earn its taxes.”

It wasn’t until the mid to late 19th century – and especially with the Mayflower Tercentenary in 1920 – that it a central pillar in the foundation myth of the United States.

The reasons were less edifying. As American society fretted about immigration from Ireland, Italy, Poland, Russia and beyond, the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant character of the Mayflower became a rallying point for a conservative ideal of what the US meant, what its values were and – ultimately – who was welcome to call it home.

The Nativist, or Know Nothing, Party which arose in the 1850s believed immigration from Catholic countries to be an organised papist conspiracy. They cloaked themselves in the imagery of the Revolution and the Pilgrim Fathers.

The reactions from those alienated by the spectacle were telling. Some Catholic schools forbade their pupils to take part in Mayflower commemorations and at a 1920 parade in honour of the Pilgrims in Washington, DC, Irish-American counter-protestors sympathetic to the cause of Irish republicanism pointedly wielded banners that asked:

“What Did England Do for the Pilgrims When They Were Starving?”

For a fresh look at pivotal moments in history, subscribe to All About History from as little as £13.

Sources:

- Sargent, Mark L. “The Conservative Covenant: The Rise of the Mayflower Compact in American Myth.” The New England Quarterly 61, no. 2 (1988): 233-51. doi:10.2307/366234.

- Arnold-Lourie, Christine. “Baby Pilgrims, Sturdy Forefathers, and One Hundred Percent Americanism: The Mayflower Tercentenary of 1920.” Massachusetts Historical Review 17 (2015): 35-66. doi:10.5224/masshistrevi.17.1.0035.