Eleanor Herman discusses how poisoning, both intentional and accidental, has played a massive role in the lives of European royal houses through the centuries

Eleanor Herman is a NY Times bestselling author of both YA fiction and historical non-fiction, and has hosted shows for History and National Geographic. She’s an expert on the torrid private lives of monarchs and her books include Sex With Kings: 500 Years Of Adultery, Power, Rivalry And Revenge and Sex With The Queen: 900 Years Of Vile Kings, Virile Lovers And Passionate Politics.

What can you tell us about The Royal Art of Poison and what inspired it?

In writing Sex With Kings and Sex With the Queen, books that examined the love lives of European royalty, I was surprised that whenever someone at court died – even a slow death – everyone assumed they had been poisoned. I decided to investigate those deaths at some point in the future to see if these individuals had really been poisoned or had died of natural illness.

In writing Sex With Kings and Sex With the Queen, books that examined the love lives of European royalty, I was surprised that whenever someone at court died – even a slow death – everyone assumed they had been poisoned. I decided to investigate those deaths at some point in the future to see if these individuals had really been poisoned or had died of natural illness.

It took while to get back to this kernel of a book idea, but I finally did.

What sort of research did you do on the book?

I read biographies of dozens of people who were rumoured to have been poisoned as well as books on the medical care – and I’m being generous with that term – in past centuries. I also read original books written in the 16th century about medical treatments and recipes for homemade medications. Some of them made my eyes pop out of their sockets – eating rat droppings to ease constipation, a mercury face mask left on for eight days. I also worked with doctors and researchers around the world to determine what killed these people, including with those researchers who dug some of them up.

What’s the earliest example of royal medication going wrong that you came across in your research?

Henry VII of Luxembourg, the Holy Roman Emperor, contracted anthrax during an epidemic in 1311 when it killed his court’s horses and jumped into the human population, with many fatalities. It didn’t kill Henry, but it did gave him stinking black lesions all over his body.

His physicians prepared an arsenic skin crème to rub on the lesions. Back then, all medication was based on trial and error – they basically tried everything and finally landed on something that worked. So they knew that a tiny bit of arsenic in a cream reduced lesions and skin rashes.

What they didn’t know was why – that arsenic, being poisonous, killed the bacteria causing the infection. Nor did they know that the arsenic could build up in the human body over time and kill the patient. They figured if it didn’t kill you quickly, then it must be okay. When researchers studied Henry’s bones in 2013, they found them loaded with arsenic. It takes months for chronic arsenic poisoning to show up in bones – a single fatal dose would show up in the digestive tract, which is the first part of a corpse to decompose. So the poison in his bones is proof that he was being slowly and unintentionally poisoned by his physicians. But it wasn’t the arsenic alone that killed him. He died of a fever, and arsenic doesn’t cause fever. But it is safe to say his body was greatly weakened by the arsenic, allowing the fever to tip him over the edge.

We know a lot about early modern cosmetics being killer, but were there any Medieval precursors where getting that perfect look could have long term consequences?

Medieval makeup was more natural than the clown look of the Renaissance with its ghastly white lead paint face and the bright red cheeks and lips from mercury-based substances. Still, some women probably used white lead powder to obtain an enviable pallor and darkened their eyelashes and brows with an oil-based mixture of kohl, which was either made of lead or antimony (a cousin of arsenic) smelted from its ore, antimony sulphide, also known as stibnite.

Or they combed their lashes and brows with a lead comb dipped in vinegar which reacted with the lead, allowing it to leach out.

A bit of the stuff would probably not harm most women, though it would depend on genetics.

Some people react very badly to it in a short time. Others could go a lifetime without any symptoms.

Poisoning as a political tool feels very Renaissance, but how was it used to settle family feuds and dynastic challenges in the Medieval period?

There is one interesting medieval poisoning case in my book. In 1329, 38-year-old Cangrande della Scalla, a warlord in northern Italy, had conquered several cities when he fell ill of a fever and died four days later. There were rumours of poison, as there always were, but modern researchers believed he probably died of malaria, a common illness in an Italian summer and one which causes high fever. Then, in 2004, Cangrande’s mummified remains were exhumed and studied. Researchers were shocked to find a poisonous plant – foxglove, also known as digitalis – in his oesophagus (he had vomited shortly before he died), his liver, stomach, intestines, and rectum.

He had clearly died of digitalis poisoning. Except digitalis doesn’t cause a fever. It seems he had a fever – from which he may very well have recovered – and his doctor was bribed to poison him in his medication.

Royals and warlords never had a taster test their medication. They just drank whatever the doctor handed them. And Cangrande, a superb warrior, threatened many Italian cities and had many enemies. Clearly, one of them had gotten to his doctor.

Do you have any other historical projects bubbling away in the background?

I’m working on another book of love affairs of powerful people. I have a strange fascination for sex and murder at the highest levels of society!

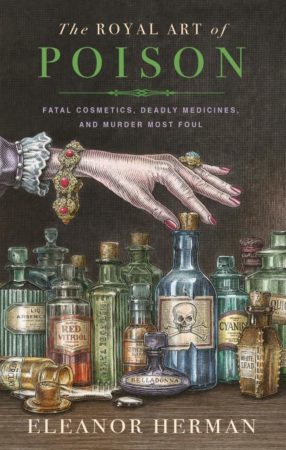

The Royal Art of Poison: Fatal Cosmetics, Deadly Medicines and Murder Most Foul is out now from Duckworth