The bloody reputation of Mongol ruler Tamerlane precedes him. Remembered for his gruesome military campaigns in which tens of millions of people may have been slaughtered, the great warrior Tamerlane — otherwise known as Timur — possessed a vast territory, stretching from Delhi to the Mediterranean. As the most powerful ruler in the 14th-century Islamic world, he was both feared and respected by his contemporaries. However, his legacy in the West mainly comes from obscene caricatures, such as Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine, in which the savage emperor treats human life with as much respect as he would an ant. But was ‘Timur the Lame’ merely a simple, brutish warrior?

A century and a half before Timur’s birth, Genghis Khan roamed the plains of Central Asia. Famously spending his life pillaging and murdering, when Genghis died, the Mongol conqueror split the spoils of his empire between four of his descendants. Chagatai, his second eldest son, was granted a large tract of land. Becoming known as the Chagatai Khanate, the steppes, deserts and mountains of the region made it one of the most beautiful parts of Genghis Khan’s old empire — but it was also one of the most remote.

Their neighbours to the north, the Golden Horde, were a scary bunch. Ruled by Genghis Khan’s grandson, these lawless tribes pillaged towns and villages from Eastern Europe to the Altay Mountains. The Chagatai Khanate, meanwhile, largely subsisted on nomadic herding and was heavily fraught with internal divisions. The khanate quickly split into two parts — the powerful east was called Moghulistan and the less fortunate west was known as Transoxiana.

It was in this divided world that Timur was born in 1336. His father, Taraqai, was a minor nobleman from the Barlas tribe — a group of nomads that made their home in the area south of Samarkand. The young Timur never stayed in one place for all that long, as his clan would repeatedly uproot themselves (and their livestock) to find the best grazing pastures whenever the seasons changed.

Realising that there was profit to be made in illegal activity, Timur turned to petty crime. His first exploits involved rustling sheep from neighbours and he quickly added banditry to his list of dodgy dealings, making travellers tremble in their boots. A man with a clear talent for violence, Timur apparently worked as a mercenary in his 20s, and was once seriously injured by an arrow during a skirmish.

Unable to walk properly on his right leg or raise his right arm, this unfortunate incident led to him being christened Timur-i-Leng — a Turkic nickname meaning ‘Timur the Lame’ — which Europeans misinterpreted as ‘Tamerlane’.

For some, this injury would mean the end of their crime sprees, but Timur’s were only just beginning. His ambitions knew no bounds and when the ruler of Transoxiana died in 1357, Timur spotted an unmissable opportunity. Aligning himself with the khan of Moghulistan, Transoxiana’s archenemy, the powerful duo installed themselves on the vacant Transoxiana throne. Ilyas Khoja, the khan’s son, was proclaimed king but Timur was the power behind the crown. However, he wouldn’t be content with being second best for long and in 1364, he switched his loyalties yet again.

This time, Timur rushed to the side of his brother-in-law, Amir Husayn, who had a score to settle with the khan of Moghulistan and by 1366, he and Timur had conquered all of the Transoxiana region. Still, Timur had no desire to share power with anyone and turned on Husayn. In a fight to the death at the city of Balkh, Husayn was assassinated and Timur proclaimed himself the unchallenged ruler.

A facial reconstruction of Timur, based on his exhumed remains

As he saw it, Timur’s mission was to restore Mongol rule to the glory days of Genghis Khan, reigning supreme over lands from Korea to the Caspian Sea. Never one for diplomacy, Timur rushed through a political marriage to Husayn’s widow, Saray Mulk Khanum. She was a direct descendant of Genghis Khan on her father’s side and Timur believed that he would be able to use this to make him a more convincing leader in the eyes of the people.

If they weren’t completely sold, they’d soon meet a grisly end. Timur wasted no time in showing his enemies who was boss in the most brutal way possible. He spent the first ten years of his rule establishing supremacy over his neighbours, demanding they surrender to him. If they refused, he would destroy their cities and enslave or murder everyone inside.

In 1383, Persia found itself on Timur’s hit list. The once mighty empire was weakened by internal strife and division, which Timur took full advantage of. Beginning with the conquest of Herat, he plundered the ancient city of its treasures and destroyed many of its important landmarks. Rumours of such horrific treatment reached other Persian cities and knowing that Timur would soon reach their walls, they had a decision to make. Some places, like Tehran, surrendered without question and Timur allegedly treated them mercifully. Others would not go down without a fight, so they were annihilated. In Isfahan, which rose up against Timur’s hefty taxation, he responded by massacring its citizens and building towers out of their skulls.

The only group of people seemingly to escape such horrors were the artisans and craftspeople. Timur didn’t spare them out of the kindness of his heart, though. He forcibly deported them to the city of Samarkand so they could get to work building his elaborate vision of an imperial capital. The city was to be the heart of the Islamic world and so Timur filled it with artists, architects and intellectuals from across Asia. Samarkand became a thriving hub of culture in the middle of Central Asia.

As well as simply being vainglorious, Timur’s reasons for building Samarkand as an ode to God and Islamic culture were entirely practical. He was keen to legitimise his rule by both invoking Genghis Khan and stressing his role as a defender of Islam. Timur’s personality cult centred on the notion that he was the ‘Scourge of Allah’, placed on Earth by God to defend the true religion. While he constantly flouted the rules of Islam — namely, that Muslims should not kill — he invoked God often as a means of support for his military campaigns, legitimising them in the people’s eyes.

But as the empire expanded, it started to incorporate peoples of different faiths, who thus had to be forced into submission. It was on this pretext that Timur invaded India in 1398. Having kept a watchful eye over the Muslim rulers of the Delhi Sultanate, the Mongol conqueror decided they had become too tolerant of their Hindu subjects and it was time for him to take matters into his own hands. In September 1398, Timur and his army of approximately 90,000 men crossed over the Indus River. Destroying cities on the way, he quickly defeated the sultan and laid waste to Delhi, which took over a year to lick its wounds. Timur even allegedly captured 90 war elephants from India and used them to haul stone back to Samarkand for a great mosque he was building in his capital.

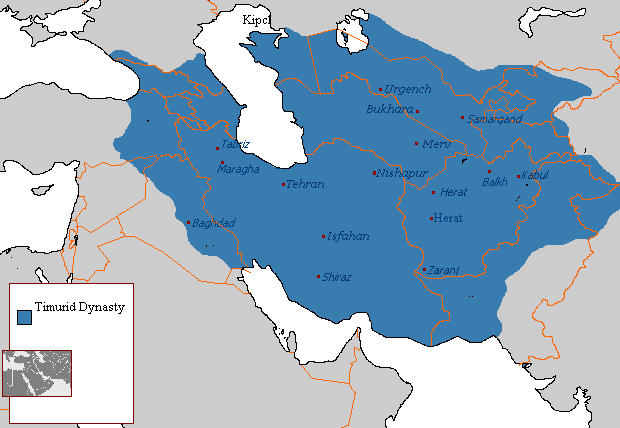

Timur’s empire at its greatest extent

A year later, Timur was on the hunt for his next conquest. This time, he looked west to the Ottoman Empire and the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. While both had powerful Muslim rulers, Timur saw them only as usurpers who had stolen territory that rightly belonged to the Mongols. The Ottoman sultan, Bayezid I, for example, had offended Timur by taking Mongol lands in Anatolia. Timur even tried to warn him off by sending him some serious hate mail in 1399. In a letter he wrote, “Thy obedience to the Qur’an, in waging war against the infidels, is the sole consideration that prevents us from destroying thy country”.

However, Bayezid wasn’t phased. He responded with a cutting remark: “What are the arrows of the flying Tatar against the scimitars and battle-axes of my firm and invincible Janissaries?” So, an enraged Timur set out to test the Ottoman elite guard’s invincibility. On his way to Constantinople, Timur reconquered Azerbaijan and Syria before inflicting yet more brutality, this time on beleaguered Baghdad. Up to 20,000 of its citizens were killed and its monuments destroyed. To Timur’s mind, these ancient cities could not possibly create potential competition for Samarkand.

When he finally reached Turkey, Timur allegedly promised not to shed blood if the town of Sivas surrendered. Trusting his word, they did. It’s said he had 3,000 of the townspeople buried alive, and Timur maintained that he had kept his promise. After all, there was no blood.

Near Ankara, Bayezid met Timur’s army on 20 July 1402 for a dramatic showdown. Timur was a shrewd tactician, so he circumvented Bayezid and attacked his army from behind. After a short battle, the sultan was captured and dragged back to Samarkand kicking and screaming. There, he was allegedly subjected to a variety of imaginative humiliations — from Timur using him as a footstool to being put on display in a golden cage.

Timur looks down on a miserable Bayezid

Ironically, some rulers in Western Europe supported Timur. They thought he was helping them to achieve Christian goals by keeping the Ottomans — a powerful Islamic empire right on their doorstep with a beady eye on Austria and Hungary — at bay. Upon learning of his victory at Ankara, England’s Henry IV and Charles VI of France sent messages declaring their congratulations to Timur. The Spanish kingdom of Castile went even further and dispatched an envoy, led by Ruy González de Clavijo, to Samarkand.

Clavijo described in fantastical detail the wondrous and exotic goings-on he saw at Timur’s court. Arriving in 1404, he described Timur’s 15 palaces, which blended nomadic and Islamic traditions. Some of them were essentially very grand tents that could be packed up and moved when necessary. Treated as honoured guests, the Spaniards dined each night at lavish feasts, which were always preceded by bouts of heavy drinking — allegedly following Mongol tradition. Timur evidently placed great significance on these feasts, as one guest was punished for turning up late by having his nose pierced like a pig.

Timur, seated, orders an invasion of Georgia – surrounded by his lavish court

Just after Clavijo and his crew started on their long journey back to Madrid in November 1404, Timur set off for what would turn out to be his last hurrah. Samarkand had been trading with Ming China for a long time, but Timur had grown tired of being treated like a vassal. For example, when a message from China arrived in 1395 calling the Ming emperor “lord of the realms of the face of the earth” (implying he was but an earthly ruler), and treating Timur like an inferior, he decided to detain the Chinese messengers. When China dispatched more envoys to find out what happened to them, Timur supposedly imprisoned the second batch as well.

Timur’s plan was to overthrow the Ming and replace them with the Yuan dynasty, Mongol rulers established by Kublai Khan. While he normally embarked on his expeditions in the spring, in order to take advantage of good weather, he bucked his own trend and departed Samarkand in December 1404 with an army of approximately 200,000 troops. His chief astrologers had told him that the stars were in favourable alignment. What could go wrong?

Unfortunately for Timur, the stars turned out to be more favourable for China than they were for him. He fell ill on the frosty banks of the Syr Darya River in Uzbekistan and died — possibly of cold — in February 1405. With no leader to inspire a victory, Timur’s army decided to turn around and head back home. The fearsome conqueror was embalmed in fragrant oils and placed in an elaborate ivory coffin for the journey to his final resting place, the beautiful Gur-e-Amir in Samarkand, his treasured city.

Gur-e-Amir in Samarkand has recently undergone a restoration

Like Genghis Khan, Timur had divided his territory between his male descendants but ultimately his empire was built on fear, terror and pillaging rather than good governance. Timur’s successors would spend the next few decades fighting each other over the land and soon his vast empire would crumble.

However, the legacy of the ‘Sword of Islam’ continues to this day. His double-great-grandson Babur founded the iconic Mughal dynasty of India, a ruling family responsible for creating stunning, Timurid-inspired monuments like the Taj Mahal and Delhi’s Red Fort. While Timur was thoroughly deserving of his bloodthirsty reputation, he left a unique visual impression on the city of Samarkand, and transformed the area from a neglected desert outpost to a centre for cultural, intellectual and religious exchange for generations to come.

Not bad for a man who began his career as a lame sheep bandit.

This article originally appeared as part of a larger feature in All About History issue 63. Discover the latest issue of All About History here or subscribe now.