“Inspirited by this wind of promise, my daydreams become more fervent and vivid. I try in vain to be persuaded that the pole is the seat of frost and desolation; it ever presents itself to my imagination as the region of beauty and delight.” These are the words of Robert Walton, a fictional explorer in Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein, but they could be the remembrances of a real-life navigator as so many have obsessed over finding a route through the Arctic Ocean. Unfortunately, this did not end well for John Franklin, who learnt the hard way that the pole truly is a seat of frost and desolation in 1845.

Over the years, this quest to find the fabled Northwest Passage — as the route through the Arctic is known — frustrated famed explorers including Francis Drake, Francisco de Ulloa, Martin Frobisher, Henry Hudson and James Cook. But in the 19th century, with better scientific and geographic knowledge, the search was taken up in earnest with over 65 expeditions to the region, compared with only nine in the 1700s and 21 in the 1600s. The Russians, Norwegians and Swedes all sought to find a way through the ice, but arguably none were more obsessed with doing so than the British.

The Northwest Passage held such an allure because it would dramatically shorten the time it would take to sail from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The only existing options — going around the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa or Cape Horn in Chile — could take several weeks and meant passing through treacherous waters. Finding a trade route through the Arctic waters would give sailors a huge commercial advantage.

The driving force behind British Arctic exploration was John Barrow, who was second secretary to the Admiralty from 1808 to 1845. The son of a Cumbrian tanner, Barrow had worked his way into the senior naval position — earning himself a baronet along the way — by proving himself a skilled administrator during the Napoleonic Wars. After France was defeated, he was charged with finding a peacetime purpose for the large number of ships and officers the British Navy had amassed.

Barrow sent the navy north to map every inlet of the Canadian Arctic, with the first expeditions setting off in 1818 — the same year Mary Shelley published Frankenstein. Over the next 27 years, naval explorers made several unsuccessful attempts to solve the enigma of the Northwest Passage, but they did build up detailed maps of many miles of Arctic coastline. Armed with these charts, Barrow was certain the route would soon be within their reach. In an 1844 letter to Lord Harrington, first lord of the Admiralty, Barrow opined, “The discovery, or rather the completion of the discovery, of a passage […] ought not to be abandoned, after so much has been done, and so little now remains to be done.”

Barrow decided to mount a major expedition deep into the Arctic Circle. Captain John Franklin was chosen to lead the voyage – but only after several candidates were either ruled out or declined. Franklin was 59 years old and had been retired for 18 years, having served as governor of sunny Tasmania for the last seven. However, in his prime, he had been to the Arctic three times and was a deeply respected explorer. He achieved nationwide fame after his first expedition, in which half of his crew died of starvation, earning him the nickname ‘the man who ate his boots’ after he was forced to literally eat boot leather to stay alive.

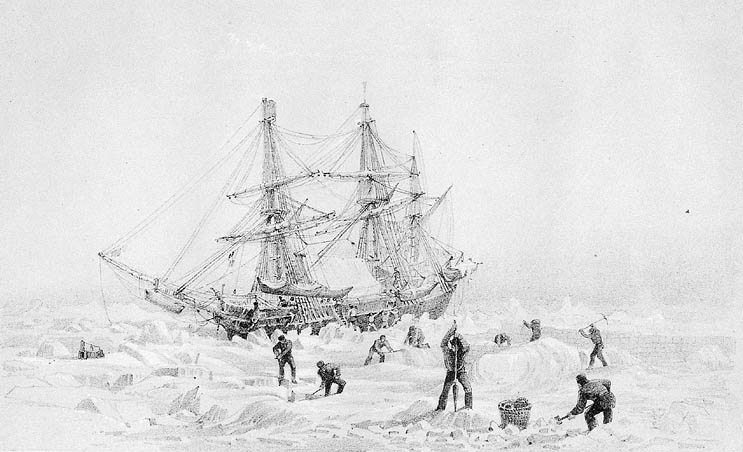

Franklin proposed to tackle the passage via Cape Walker and Bank’s Island. If that proved impossible, he would head north through the Wellington Channel and go north of the Barrow Strait (named in honour of John Barrow). In May 1845, he set off with a 128-man crew and two ships: HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. While these were warships, they had been adapted for polar exploration for James Clark Ross’ expeditions to Antarctica in 1840.

Both vessels had 25-centimetre belts of timber, sheet iron on their bows to cut through sea ice and to take the strain of being trapped in it, and beams protecting the hull. They also benefitted from tubular boilers and steam apparatus, which provided hot water and heating. A 25-horsepower locomotive engine was fitted into the Erebus, purchased from the London and Greenwich Railway, and Terror was fitted with a 20-horsepower engine.

Erebus and Terror boasted a library of 2,900 books and journals between them, while their food stores were packed with 15,099 kilograms of tinned meat, 4,036 kilograms of preserved vegetables and 11,628 litres of concentrated soup. They also housed 4,286 kilograms of chocolate, 3,215 kilograms of tobacco, 910 litres of wine and 4,218 kilograms of lemon juice to fight scurvy. They should have had enough provisions to last seven years.

On 12 May, the ships were towed down the Thames from Woolwich to Greenhithe, Kent, where final preparations were undertaken and gunpowder and magnetic instruments were brought aboard. The departure date was 15 May but they were delayed. On 19 May, the screw steamer HMS Rattler finally towed the ships into the North Sea.

On 25 June, they crossed the Arctic Circle and arrived in the Whale Fish Islands off western Greenland five days later. Anchored in Baffin Bay, they took on even more provisions, transferred from the supply ship Barretto Junior, which put Erebus and Terror significantly overweight. Two British whalers encountered the ships, still in Baffin Bay but preparing to head east into Lancaster Sound, on 26 July. They were the last Europeans to ever see the explorers alive.

“They should have had enough provisions to last them seven years”

When a year passed and there was no word from Franklin, the Admiralty were initially unconcerned. They believed the lack of communication meant success as the captain had told them to only expect him back when provisions had been exhausted. By 1847, the Admiralty were sending communiqués to Hudson’s Bay Company traders and whaling ships to keep an eye out for signs of the Franklin expedition. Others back home were growing concerned, but the Admiralty refused to act. In March 1848, they eventually offered 100 guineas to any whalers with news to share regarding Erebus and Terror. Franklin’s wife, Jane, too, had drummed up £2,000 reward money for information.

Ross was issued orders on 9 May 1848, to find out what had become of the expedition. He would take off in HMS Enterprise for Lancaster Sound, Barrow Strait and the Wellington Channel, sea ice permitted. HMS Investigator, the other ship in the search party, would go and look for Franklin along the Boothia Peninsula and Prince Regent Inlet.

Ross’ team arrived in the Whale Fish Islands and discovered that Baffin Bay was impenetrable due to sea ice and no crossing could be performed. In late August they reached Baffin Island, yet their progression was hindered further by sea ice. Ross had been exceedingly optimistic in his plans, but now he was faced with diminishing food stocks. The ships turned back. When Ross returned to London, he faced severe criticism from the Admiralty and Franklin’s widow.

In 1850, the Admiralty offered a £20,000 reward for any private vessel that could offer “efficient assistance” to the Franklin ships. By now they knew that Erebus and Terror would be in danger or succumbed to calamity. When they kicked a host of search and rescue missions into gear, the irony was stinging: more ships were sent out to find Franklin’s expedition than had ever embarked on Northwest Passage expeditions.

“Graves, Captain Penny!” cried the messenger. HMS Advance had been searching off Beechey Island when the crewman informed his captain that graves had been discovered on a stretch of land amid the snow and slate ground.

The graves and tombstones were well constructed and proper rites had been followed. Further investigation nearby yielded ropes, cloth, wood and brass bits. The search party was baffled to discover 600 empty tin cans they found filled with pebbles. If their contents had gone bad, why were the tins filled with stones?

On 20 April 1854, Dr John Rae of the Hudson’s Bay Company discovered the truth of what had happened to Franklin and his men. At Pelly Bay on the Boothia Peninsula, and much further eastwards at Repulse Bay, Rae met Inuit who said a party of ‘Kabloonans’ (their word for white people) had starved to death. About 40 men were seen dragging a sledge and boat on King William Sound in spring 1850 and they explained through hand signals that their ships had been crushed by ice. Later in the summer, the Inuit hunters found their bodies scattered — some in a tent, some in the boat, others where they fell from exhaustion and starvation.

To back up their story, the Inuit people had a gold cap band, silver cutlery and Franklin’s Hanoverian order of Knighthood in their possession. They admitted to Rae that paper records discovered among the bodies were destroyed. The most gruesome detail was not something Victorian Britain had wished to hear — the survivors had turned to cannibalism, eating the dead to stay alive. Famed novelist Charles Dickens was so offended by the accusation passed on to the Admiralty and newspapers that he referred to the Inuit testimony as the “vague babble of savages”.

In 1859, Leopold McClintock of the British Navy returned to England with a firsthand account of the crew’s experience. The explorers left notes in a tin container, buried under piles of rocks, known as cairns, on King William Island for others to find — a common practice at the time. The first message, left on 28 May 1847, said the ships had wintered at Beechey Island, but declared “all well”.

The second message, left on 25 April 1848, was less cheerful. The ships had been trapped in the ice since September 1846 and Franklin had died the following June. The note confirmed 24 other crew members had died and the remaining 105 survivors had resolved to abandon the ships and head south towards Back’s Great Fish River.

What exactly happened between the crewmen’s last note and when the Inuit met the survivors in 1850 is unclear. However, skeletons dotted along King William Island suggest the men did march south, resting where they fell, weak from hunger, scurvy and the extreme cold. Despite Dickens’ reservations, a forensic analysis showed that many of the bodies had been eaten by desperate survivors

But what actually killed Franklin and his men before the ships were abandoned? The carefully tended graves found by HMS Advance at Beechey Island were exhumed in 1984. The bodies of John Torrington, William Braine and John Hartnell underwent a thorough autopsy, their remains remarkably preserved by the permafrost.

Torrington’s body, in particular, suggested that he had been ill for quite some as it was so thin that his ribs were visible, while his lungs indicated that he’d recently had pneumonia. However, analysis of his hair showed signs of lead poisoning. Many believe this can be traced to the tinned food in the stores, but the ships’ elaborate heating systems would have used lead pipes, which could have slowly poisoned their water supply. All of this suggests the expedition was doomed from the start.

In Frankenstein, Robert Walton eventually decides to abandon his quest for the Northwest Passage rather than risk being destroyed by the ice. Thanks to Franklin and explorers like him, we are not ignorant: the Northwest Passage was found in 1854 and, thanks to sea ice decline, is increasingly used. Close to 170 years after they were last seen, the wrecks of Erebus was found in 2014 and Terror in 2016, both around 60 miles south of where experts believe they were initially trapped in the ice. However, the mystery of what exactly happened to the ships’ passengers endures.

This article first appeared in All About History issue 55 in August 2016. To discover more amazing stories from the past, subscribe to All About History from as little as £13.