How four penniless Jewish immigrant siblings changed the face of entertainment forever and wrote their own fairy tale

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

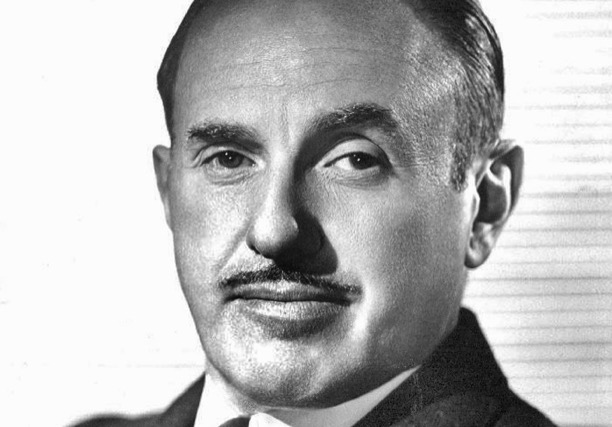

Jack Warner always wanted to be famous. Actually, make that adored, powerful, rich and famous. Born Jacob Warner in impoverished Canada to Jewish immigrant parents in 1892, he changed his name to something more theatrical: Jack L Warner. As a young man he grew up obsessed with images, hanging around photography studios in the hope of being used for test shots. While his brothers were recognising the potential of early film projectors, investing in a Kinetoscope projector, Jack made money singing in theatres, showing little interest in – or aptitude for – the less glamorous side of show business.

Willed on by his parents and clubbing together with his brothers – Albert, Harry and Sam – Jack toured the Northern states showing old prints of The Great Train Robbery, drawing enough cash to buy a series of local theatres and launch their own distribution company, the Duquesne Amusement Company. However, the brothers’ ambition didn’t stop at a network of provincial theatres. The Warners had their sights set on global domination.

At the turn of the century many others were also heading west to seek a new life. One of these was Harvey Wilcox, who bought 160 acres (64 hectares) of land to the west of Los Angeles in the ironic hope of founding a conservative community. On the train from Kansas, Wilcox and his wife got chatting to a woman who talked of her summer home: Hollywood.

Wilcox’s vision of founding a community became a reality and in 1910 Hollywood officially became a part of Los Angeles. At the same time, a group of actors and directors – drawn to the area by the sunny climate, lack of taxes and freedom from patents issued by Thomas Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company – started shooting motion pictures in what is now the film-making capital of the world. In 1911 Hollywood got its first studio, when the Blondeau Tavern on Sunset Boulevard became the Nestor Film Company – firing the starting pistol on a gold rush that would take place over the next two decades.

A few years later, in 1917, Jack Warner had been dispatched to Los Angeles where he bought the rights to My Four Years In Germany, a memoir by the US ambassador to Germany who lived in that country during the First World War. In the face of threats from local theatre owners and impressive offers from distributors, the brothers held fast and premiered the movie themselves, making a small fortune in the process. Riding anti-German sentiment following the war, the film was a smash. Warner Brothers now had a place at the top table of American film producers.

In 1918, the siblings formed Warner Brothers West Coast Studios, later incorporated as the more recognisable Warner Brothers in 1923, and moved to Hollywood. Jack shared production duties with brother Sam while Harry and Albert sold distribution rights and they launched enthusiastically into a series of low-budget farces. However, the films were not a success and the company dangled on the edge of a financial chasm – moving to a down-at-heel neighbourhood that locals referred to as Poverty Row. Salvation was to come in the most unlikely of forms.

A German Shepherd called Rin Tin Tin proved to be the saviour of Warner Brothers. The trained dog – rescued from a battlefield by a US soldier in the First World War – became the star of a series of silent films of derring-do. The canine appeared in over 27 Hollywood films for Warner Bros, becoming famous around the world. Noting Warner Brothers’ flirtation with bankruptcy, Jack called Rin Tin Tin “the mortgage lifter.” The German Shepherd was so popular in Hollywood that the Academy of Motion Pictures voted the dog best actor in 1929; sadly the Academy insisted that a human actor take the Oscar. The Rin Tin Tin films were written by Darryl F Zanuck, who later became Jack Warner’s executive producer and right-hand man before his dislike of the Warners drove him to what would become 20th Century Fox. Adding names such as director Ernst Lubitsch and star John Barrymore to Warner Brothers’ roster boosted sales and also lent the studio some respectability.

On the back of these successes – and fearing being shut out by the established studios – the Warners expanded, purchasing theatre companies, building a laboratory to develop film and investing in new hardware. Warners led the way with a vertical model. Rather than being a cog in a larger mechanism, the studio owned it all, from production to distribution to exhibition. Most moguls came from theatre companies so already had distribution tied up (some had virtual monopolies in certain cities) while adding production allowed for the greatest return on investment. The Warners had to beg, steal and borrow to be able to take on the existing studios.

As well as Warner Brothers, four other big studios were to emerge in the 1920s, which would become Hollywood studios recognised today: Paramount was headed by Adolph Zukor and had a reputation for quality silent films; 20th Century Fox was created from a merger in 1935, headed by Warner’s old colleague Darryl F Zanuck; MGM had a huge talent roster and produced many of the era’s most famous pictures; RKO concentrated their efforts on films noir.

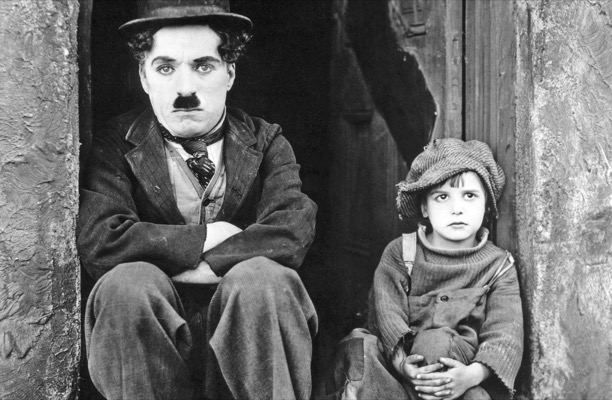

By the 1920s, most US film production occurred in or near Hollywood. By the end of the decade, there were 20 Hollywood studios averaging about 800 film releases in a year – far in excess of modern Hollywood. Films were being manufactured in modular format, aping the success of Henry Ford’s production-line process. Swashbucklers, historical or biblical epics and melodramas were most popular, though Warners would blaze a trail with gangster capers and Universal became known for its horror films. Meanwhile, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd and Laurel & Hardy were popular for their comedic movies.

The studio system that emerged enforced long-term contracts for stars and rigid control of both them and directors. This system ensured strong profits and a de facto monopoly – by 1929, the ‘Big Five’ studios produced over 90 per cent of the fiction titles in the States. Studios also distributed their films internationally, hogging the profits at every step of film-making and distribution.

The studios didn’t just control the logistics of film-making though. They would snap up promising, good-looking young actors and actresses and construct a new public image for them, often changing their names, putting them through vocal coaching – a necessity for many in the emerging talkie era – and even forcing some to undergo plastic surgery. Studios would choose which films their star made, arrange their romantic lives and force them to adhere to strict moral codes. There was significant irony to this. Jack Warner was used to having his pick of the starlets, enjoying the power that came with the success of the Warner Brothers’ talkies.

In 1925, buoyed by financial and moral support from United Artists – an independent founded by Douglas Fairbanks Sr, Mark Pickford and Charlie Chaplin – the Warners embarked on a set of acquisitions, appointments and impulsive purchases. Chief among them was a bunch of old machinery from a radio station, because Sam and Jack had an idea. While silent films had their appeal – they were universal due to their lack of a specific language and sound-synchronisation technology was appallingly basic – the two brothers recognised the fantastic possibilities offered by talking pictures.

Chief among the new technologies they pursued was the new Vitaphone film sound process that allowed for synchronisation of sound and moving images, with sounds played on a gramophone. By the mid-1920s it was clear to Jack, despite his initial personal doubts, that the studio that successfully developed sound would reap immense rewards. Other studios were investing heavily in the technology so Warners couldn’t afford to be left behind. While the resulting Vitaphone technology was basic, Warner Brothers quickly kitted out their theatres with new kit, cementing them as the leaders of the new media but at the cost of $3 million; it was an enormous gamble.

Championed by Sam Warner as a cheaper alternative to paying for live music in theatres, and in the face of resistance from Harry, the new technology paved the way for 1926’s Don Juan. Although music and sound effects featured, there was no synchronised speech. Still, the reception to the film was overwhelmingly positive – it had changed the face of the industry. But while the studio enjoyed critical success, the bottom line wasn’t nearly so healthy and the cost of producing the film and fitting out theatres with the new Vitaphone projectors almost wiped them out.

With the studio mortgaged up to the hilt, the brothers embarked on another ambitious plan: the next project would feature synchronised dialogue. 1927’s The Jazz Singer was the first to include speech and was a smash hit, earning Warner Brothers millions of dollars, despite a budget that was considered exorbitant at the time, concerns over their star’s acting abilities and the quality of the script. Realising Jolson’s claim to the audience that “you ain’t heard nothin’ yet”, Warner’s stock went stratospheric; at $132 a share it was worth nearly seven times the value prior to The Jazz Singer. The gamble had paid off, and handsomely too – the film ensured the studio was now swimming in cash.

The celebrations would be short-lived, though. Jack had noticed that his brother Sam had been struggling with his balance and suffering from nosebleeds – the result of undiagnosed infections caused by abscessed teeth. Following months of ill health, Sam Warner fell into a coma and died at the age of 40, the day before The Jazz Singer’s premiere.

While he was devastated by the loss of his closest brother, this was Jack’s moment. Without Sam, he became the studio’s head of production, inheriting his brother’s drive but combining it with a fire and no-nonsense attitude. Unlike Sam, who was generally liked, Jack gained a reputation as an uncaring boss – happy to slash costs and lay off staff for the sake of the bottom line. Under his leadership the studio gambled the astonishing sum of $100 million on the purchase of rival film studio First National. When The Wall Street Crash of 1929 – while not denting the film industry as badly as other industries – occured it meant that, for a while, money was tight.

The studio’s response was to ramp up production to a staggering 80 films a year by 1929. With no one to check his behaviour, Jack became notorious as one of the most unpleasant men in Hollywood – in a town filled with unpleasant men no mean achievement. Further acquisitions and expansion would make Warner Bros one of the Big Five studios and Jack Warner one of Hollywood’s most powerful players – he was, by this point, a huge success by any reasonable measure. Warner Bros had matched, then bought out and finally beaten rivals into submission, becoming the equal of the four biggest studios, MGM, 20th Century Fox, RKO and Paramount by 1930. It had taken 20 years but the Warner Brothers had done it.

The impact of Warner Bros is hard to overstate. With the release of The Jazz Singer the brothers revolutionised the industry – some stars were finished overnight while others saw new opportunities opening up. Silent films were dead within one or two years. Beyond that the structure of Warner Bros – with stars under contract, films made in-house at studios, owned outright and distributed to theatres owned by the studio – combined with pioneering use of new technologies and rampant acquisition of theatre chains and other studios amounted to an economic powerhouse. The four brothers were instrumental in introducing the studio system that Hollywood would become known for – and it was unbeatable.

From poor outsiders, immigrants, they had sweated, gambled, bartered and sacrificed to reach the apex of Hollywood. Jack Warner – who had once sung, badly, for pennies – was a powerful studio boss; the Golden Age of Hollywood arriving. For an ambitious boy who had always yearned for power, respect and adulation, it was a classic rags-to-riches story, worthy of a film script from one of Hollywood’s greatest studios.

Originally published in All About History 15

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!