The bobby on the beat is one of the iconic symbols of the Victorian era, seemingly fixed and eternal in popular culture, but the the growth of professional police forces in the mid-1800s was a shock to the system. It transformed society, created a new professional class and opened up debates about privacy that still rage in modern Britain. Inspired by her own great-great-grandfather’s long and storied career as a constable in Bradford, West Yorkshire, Gaynor Haliday’s new book Victorian Policing (available now from Pen & Sword) offers an incredible window into the formative decades of modern policing. We spoke to Gaynor to find out more about law and order in the wild West Riding.

How much did you know about your great-great-grandfather when you were growing up and what set you off down this research rabbit hole?

I first learned about my great-great-grandfather being a policeman when my mother brought home Street Characters of a Victorian City from the local library, over 20 years ago. Its author, Gary Firth, had selected a number of watercolour portraits created by John Sowden in the late 1880s, with short descriptions for each of the characters. Included in the compilation was my great-great-grandfather, Police Constable Thomas Bottomley. The notes claimed that he’d been known for his sensitive style of policing and rather than taking a drunk to the police station would whisper kindly in the old soak’s ear, urging him to go quietly home to his wife and bairns. The citation also stated that he’d never had a case in court in 30 years and was nicknamed ‘Tom Bott’ by the criminal classes, who knew him well.

What struck me about the portrait, which had been on display in Bradford’s Bolling Hall Museum at some time, was (apart from his fabulous white beard) the facial similarity between Thomas and my maternal late grandmother (his granddaughter).

I’d been researching the family tree since about 2009, using Ancestry as a platform. When the West Yorkshire Police records were added a couple of years ago I found PC 50 Thomas Bottomley’s scant details in the disciplinary book. He’d only been in bother once, for neglect of duty, for which it seems he was reprimanded by the chief constable, but the information did reveal that he’d joined the force on 7 February 1852, and been superannuated sometime just before mid-May 1891, when someone else was appointed as PC 50.

Taking advantage of a £1 offer for a month’s subscription to British Newspaper Archives, I searched for PC Bottomley and was amazed to find that far from being a gentle, no-action taken, bobby, he’d taken many drunks into custody, been involved in many arrests (and assaulted for his troubles), often given evidence in court, helped solve murders and discovered a dead man at the bottom of a quarry.

Needing to find more, I visited the West Yorkshire Archives in Bradford to examine the Watch Committee Minute Books – dusty tomes containing handwritten records of the weekly meetings. Here was Thomas’ name on 7 February 1852, with around twenty other men who’d joined as supernumeraries on the same date. Also recorded was his retirement date on 30 April 1891 aged 69, with his pension entitlement of 20s 9d per week, exactly two-thirds of his wage. It seems he’d been Bradford’s longest serving constable.

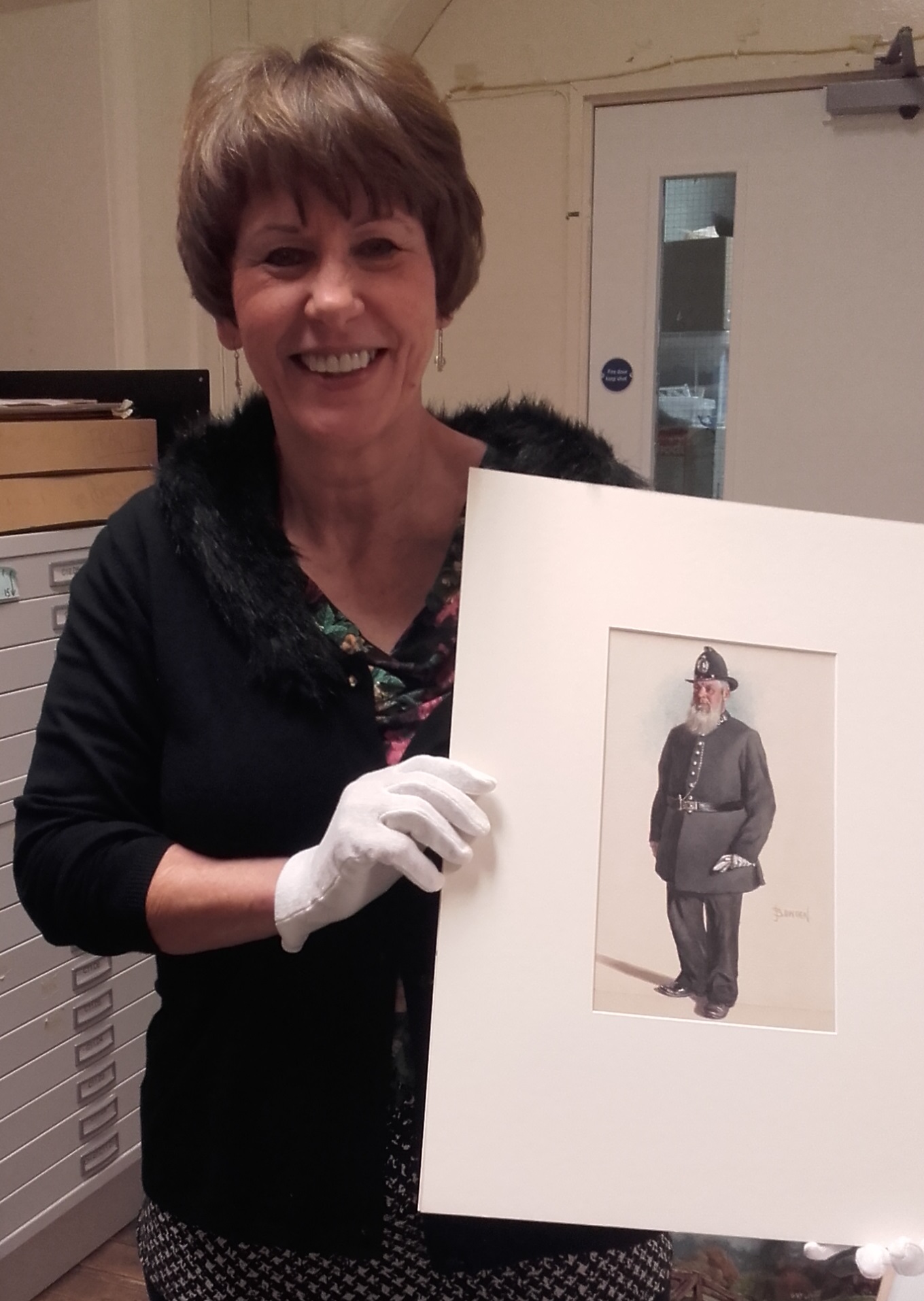

It wasn’t until November 2016, that I finally tracked down the original portrait of Thomas squirreled away from view in Bradford Art Gallery’s archives. Literally a ‘warts and all’ painting, his image is of a stout, proud-looking man in uniform, with a large silvery-white beard. Sowden notes on the reverse that this is Thomas Bottomley of the police force and that he is known as ‘Old Bott’ (contrary to the book). It’s easy to imagine the ne’er-do-wells calling out to him, ‘Na’ then, old Bott, ‘Ow’st’a’ doin’?’ as he pounded his Manningham beat!

But I was also fascinated by the information I’d found in the watch committee’s records; the trials and tribulations of both the watch committee which set up and oversaw the running of the force and of the men who had to appear before it, faced with disciplinary action for their misdemeanours. The minutes paint such a vivid picture of life in a Victorian borough (as Bradford was at the time).

Regional police forces really exploded with the various Police Acts, particularly the County and Borough Police Act 1856, but what was actually involved in setting up a police force?

Bradford’s watch committee minutes record how they established a police force after the town was incorporated as a borough in April 1847. Most forces followed similar procedures, whichever Police Act spurred them into setting up a police force. Bradford’s first meeting to discuss the matter was on 13 November 1847, when it formed a sub-committee to define the limits by which to extend its existing policing arrangement and to suggest the number of police necessary for purpose, with their respective wages. It was proposed Charles Ingham, already a constable of the town, be appointed chief constable. However, on reflection it was considered preferable to advertise the position more widely, perhaps to find someone with greater experience. In the event, William Leveratt, a superintendent from the already well-established Liverpool force, was offered the position on 26 November. By 2 December he was able to deliver his recommendations on the policing of Bradford to the sub-committee.

Advertisements were placed for ‘Constables Wanted’, interviews were held and men appointed within days. In tandem with this were tenders for the manufacture and supply of uniforms and other accoutrements (belts, truncheons, rattles, cutlasses etc.). Rule books were printed, books and documents procured, and by 1 January 1848, the Bradford Borough Constabulary Force was in place, manned and clothed but not quite fully-equipped.

A detailed report of the men, their clothing and accoutrements was sent to the Rt Hon Sir George Grey, Baronet, Home Secretary, quantifying the annual cost as £3,749.

How were the police perceived in these early days? Were the general public receptive or hostile?

The general public, who were now obliged to fund these professional forces through their rates, were not entirely impressed. The more literate frequently complained, through letters to the newspapers, of the loss of privacy, freedom and so on, caused by the fact that the police were always there, watching everything. People were uncomfortable at first, but perhaps they warmed to the police when they realised they could be easily found and called upon in a crisis. One incident reported that a householder had gone to fetch PC Thomas Bottomley from his home when the man’s wife had found an intruder in their bedroom at 3.00am.

Perhaps feeling their positions as justices of the peace threatened by a professional police force, magistrates were not too keen on the police either. They often complained about police activity and in Worcestershire in 1844, one over-zealous JP even tried (and failed) to disband the force set up in 1839, to revert to an old system. But even the magistrates saw sense in the end, when they observed how crime had reduced in counties with proper policing – some of the reduction being because the criminals had moved to areas where a lack of police meant they could get on with their ‘jobs’.

What sort of person became a policeman in Victorian England, particularly in West Yorkshire where your great-great grandfather swung his truncheon?

Men from all walks of life became policemen. The wage was set to attract semi-skilled workers, so in an area such as the West Riding of Yorkshire, a mix of rural and urban districts, men who came forward usually either worked in mills, mines or factories, or on the land. My own ancestor had been a woolcomber and it was probably the downturn in work, bought about by the introduction of machinery, which led him to choose a more secure career path. Although he never progressed beyond being a constable (though he achieved the highest position as a Merit Constable), others did take the opportunity to rise to higher ranks. The few who made it as far as superintendent joined the middle classes. This might have proved quite difficult for someone who’d been a rough bricklayer for example, but now had to mix socially with the great and good of a town.

In the West Riding it usually took an ordinary man around twenty years to attain a superintendent post, but those who were better educated or had a military background could ‘fast-track’ from constable to superintendent in less than half the time.

The image of the Victorian policeman is coloured by Jack the Ripper and Sherlock Holmes, and the long shadows they cast in popular culture that makes Victorian policemen look helpless and inefficient. How were crimes solved in the era before forensics?

One of the issues facing the police was their visibility – always in uniform and pounding a regular beat. Although this conspicuousness may have helped to deter some criminals, others could gauge how long a constable would be away from a particular street and know they could commit a crime whilst he wasn’t watching. This led to the introduction of plain-clothed detectives, usually brought in to solve a crime after it had happened. There was some resentment by uniformed men, who felt the detectives swept in and took the glory (and any financial perks), when often it was the bobby on the beat who had to point out the potential perpetrators of a crime. The constable was required to know every inch of his beat, who the residents were, the suspicious characters and the likely trouble-spots. This knowledge, diligence and vigilance was vital in solving crime.

One instance of crime solving was when a murder was committed almost on the doorstep of the Manningham police station in March 1872. Thomas Bottomley’s vigilance led to him discovering the victim’s empty purse and gloves in a nearby brickyard. Also with these items was a tatty pair of trousers. Prior questioning of people who’d seen the victim shortly before he met his death had revealed that he’d purchased a new pair of corduroy trousers late that afternoon, and had been seen carrying his parcel home. It transpired that one of the gang who’d attacked the victim had discarded his old trousers for the new pair, but later pawned them. The pawnbroker came forward when a description of the trousers had been circulated and this led to the identification and apprehension of the murderers. Nowadays the police would just carry out forensic testing of the tatty trousers and soon find out who they’d belonged to!

Looking through the lens of police and court reports, you get a sense of just how easily life can go wrong. What did your research tell you about society in a Northern industrial town like Bradford?

Life was tough for many in the industrial towns. Although occupations were labour-intensive, so there would appear to be plenty of employment, a downturn in trade could soon lead to workers being laid-off. With no welfare state they’d have to find work elsewhere, often at a lower rate of pay. There were few employment laws either, so bosses could hire and fire at will, or cut pay.

A secure job in the police force, unlikely to experience any downturn in trade, would seem attractive, but the hours were long, there were fewer rest days and the ever-present danger of assault or injury. Discipline was tough too, and the working class men who became policemen were similar to their peers in other occupations – they liked a drink. For many this was their downfall and they didn’t survive long in their new job.

When the USA Representative, William McKinley, later president, imposed his McKinley Tariff on all imports in October 1890, to protect domestic manufacturers, Samuel Lister reduced the wages of the velvet weavers at Manningham Mills by 25 per cent to compensate for the additional cost of exporting the cloth they produced. It affected around 1,100 of the 5,000 workforce. Negotiations with management failed and they withdrew their labour in December. A strike fund was set up, which lengthened and deepened the strike until almost all departments were out. The dispute lasted till mid-April 1891, when the workforce finally returned, but not until there had been huge riots outside Bradford’s town hall and several police had been injured in the cross-fire as they tried to bring the rioters under control.

Although the workers were defeated after five long months, their struggle led to the strike’s leaders realising the need for their own political party. That year the Bradford Labour Union was created, followed by the Bradford Independent Labour Party in 1892. Other industrial towns followed suit and in 1893, Bradford hosted 120 ILP delegates to form the national Independent Labour Party. It represented the growing socialist movement, which later joined with other similar causes to become the Labour Party in 1906.

Gaynor Haliday’s new book Victorian Policing is available now from Pen & Sword. For more curious from Victoria Britain, subscribe to All About History for as little as £26.