Macbeth is one of William Shakespeare’s most famous works, having kept audiences spellbound with its tales of murder, betrayal and a sprinkling of the supernatural for centuries. It tells of an ambitious noble whose lust for power sees him kill his friend and king to gain the throne, spurred on by a prophecy from a trio of witches and his ruthless wife. Macbeth’s treachery sees his enemies come back for revenge and he dies alone and friendless at the end.

We do not know a lot about the real Macbeth, who lived from 1005-1057. But what records we have suggest his rise to the throne, while quite different to Shakespeare’s tragedy, was no less bloody. We find a man whose ambition drove him to become ruler of the kingdom of Moray and then the whole of Scotland — a feat achieved over the slain bodies of his enemies. The Bard didn’t have to look hard to find drama and intrigue, but he did not tell the whole story. Macbeth was not as underhanded as his literary counterpart. He also ruled a strong and stable Scotland for almost a decade, putting it on the European map as a place of international renown.

King Macbeth, in a portrait painted in 1680 – long after he (and Shakespeare) had died.

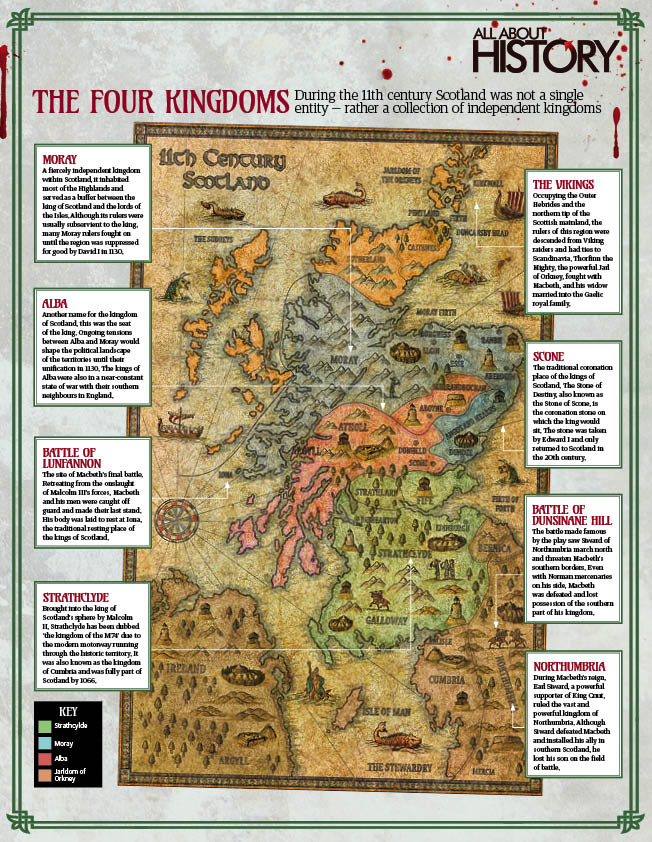

Scotland in the 11th century was much different to the one we know today, made up of a patchwork of loosely connected kingdoms. Alba was the largest and most central state. The seafaring Jarldom of Orkney, ruled by the Lord of the Isles, encompassed the Outer Hebrides and the northern tip of the mainland. Strathclyde made up the area running from Glasgow to Penrith. Moray, where Macbeth’s family ruled, included Inverness and Aberdeenshire.

It is impossible to ascertain exactly how these kingdoms interacted with each other, but many historians think that each was ruled autonomously by a ruler that was subservient to an overarching king of Scotland. This system would have been similar to the Irish high kings of the same period. Ruling from his seat in Alba, Malcolm II was the high king of Scotland when Macbeth was born.

Generations of war and dynastic conflict had seen Scotland’s crown pass from brother to brother rather than the more familiar primogeniture, which hands the crown down from father to son. With many Scottish kings in the 10th and 11th centuries being killed by their rivals, this system ensured that someone was always ready to rule without the number of claimants to the throne growing ever larger.

However, Malcolm was a powerful figure in the region. Killing his predecessor, Kenneth III in 1005, and allegedly securing his territory by defeating a Northumbrian army at the Battle of Carham (around 1016), he not only confirmed the Scottish hold over the land between the rivers Forth and Tweed but also secured Strathclyde about the same time.

As savvy a politician as he was a general, Malcolm saw the Norman feudal system down south and decided to defy tradition. He would, from now on, pass the crown directly to his heir. He set about removing all the rival claimants to the throne in a very direct way — by killing them. It’s highly probable Macbeth was Malcolm’s younger cousin, so he was lucky to survive this cull. Malcolm is Medieval Scotland’s only real example of a serial killer. His consolidation of power was arguably far worse than anything the real Macbeth ever did.

Malcolm II in a blood red outfit – fitting for the man who had so many killed

A major flaw in Malcolm’s plan, though, was that there is no evidence of him actually fathering a son, only daughters. Instead, his grandson Duncan would inherit his crown, becoming Duncan I. This is the supposedly good king Macbeth betrays in Shakespeare’s play.

The kingdom of Moray was ruled by a mormaer, meaning high steward, and was the position held by Macbeth’s father Findlaech, or Findley. This means Macbeth’s name was quite unusual. ‘Mac’ usually means ‘son of’ — like ‘Macduff’ would mean ‘son of Duff’ — but as Macbeth’s father was called Findley his name meant ‘son of life’. In later life, Macbeth would be known by another name, ‘The furious Red One’, presumably given for his prowess on the blood-splattered battlefield.

Despite Malcolm II being the high king, Findley clearly didn’t respect him as he sent a constant stream of raiding parties into his territory. This outward show of aggression was tempered by an internal feud when Findley was usurped and murdered by his nephew Gille Coemgáin. The new ruler of Moray would then go on to marry a Scottish princess, Gruoch — from the line of Kenneth III, who Malcolm had killed to assume power. As well as inheriting Moray, their son Lulach could make a claim for the high kingship.

While this might have placed the boy in Malcolm’s crosshair, Macbeth got in the way. Findley’s son wanted to retake Moray. In 1032, Gille Coemgáin and 50 or so of his followers were locked in a hall that was set alight, roasting all those inside. While there is some ambiguity as to who ordered the killing, Macbeth stood as the one to benefit most. The fire saw Macbeth’s opposition die gruesomely and he now stood as uncontested ruler in Moray. Shrewdly, Macbeth also married Gillecomgáin’s widow and took her son as his ward. This is one of the few examples of Macbeth displaying the sort of underhandedness that Shakespeare would make him synonymous with.

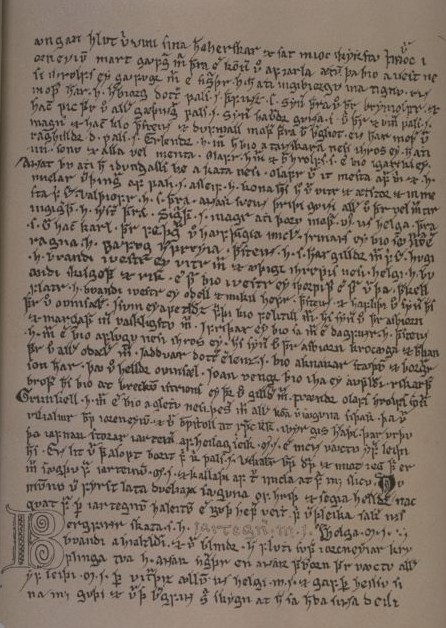

No sooner was Macbeth king of Moray, he had to look to his northern borders to combat the growing power of Earl Thorfinn the Mighty. The Norse Orkneyinga Saga names Karl Hundason as the king of Scots and relates Thorfinn’s struggles with him to assert his control over the northernmost points of Scotland, namely Caithness and Sutherland. Hundason has been suggested to be Macbeth, although the reason for the ambiguity is unknown. If true, Macbeth failed to take away Thorfinn’s positions on the mainland, but as the Norse jarl got his nickname from his massive frame and skill in battle, he may have been out of his league.

The Norse Orkneyinga Saga is a fantastic contemporary source about the history of Scotland

When Duncan took the crown in 1034, Macbeth may have seen a chance to extend his sphere of influence and gain the throne of all of Scotland. Duncan was seen as an ineffectual ruler, being described as “a man promoted well beyond his station” — a far cry from the fearsome Malcolm II. Our understanding of Duncan’s reign as peaceful comes largely from the play, but it seems that Shakespeare cherry-picked the good aspects and left out the drudgery to better place the king as a counterpoint to Macbeth’s tyranny and ambition.

Duncan I met his end at Macbeth’s hand, but the deed was not done in the dead of night in a bedchamber. The two met on the battlefield in 1040, near Elgin, and Duncan was slain. Whether it was Macbeth who did the deed is unknown, but some poetic licence can see this confrontation being a dramatic showdown.

The British Isles have a history of royal usurpers and Macbeth certainly fits the category. Many of the kings before him had taken the throne by brute force. In fact, violent succession was so commonplace in Scotland at the time that Duncan I’s peaceful coronation was somewhat of an oddity.

Aside from having killed Duncan, Macbeth could also claim lineage to the Scottish throne through his mother’s bloodline and, of course, his stepson Lulach. His claim was strong enough that he was crowned with no opposition. After his death, Duncan’s son — another Malcolm — would flee the country.

Once king, Macbeth faced very little opposition for much of his reign. However, having clashed with the Jarl of Orkney as the ruler of Moray, his kingship was contested in 1045 by Duncan I’s father, Crinán, abbot of Dunkeld. This powerful man could have been a real thorn in Macbeth’s side, but after a brief and violent struggle Crinán and 180 of his men lay dead. This was not an age of pitched battles in Scotland and many of the conflicts fought by Macbeth would have been on a much smaller scale to, say, the Battle of Hastings, which was fought in 1066 — about a decade after his death.

Crinán’s rebellion was Malcolm II’s bloodline trying to reassert itself and place the future Malcolm III on the throne. Just as in the play, Macbeth had won the crown by bloodshed, and the dead were coming back to haunt him.

However, after seeing this rebellion off, Macbeth did something no other king of Scotland had ever done: he went on a pilgrimage to Rome. This journey could have taken months, so this meant he must have been confident enough in the strength and stability of his reign that he did not fear usurpation. Macbeth was invited to a papal jubilee hosted by Pope Leo IX.

While in Rome, Macbeth “scattered money like seed to the poor”, implying he possessed great wealth. Scotland was flourishing, or at least not in financial trouble under his kingship. Macbeth’s visit to Rome also indicates a knowledge of the wider world and that Scotland was firmly on the European map during his kingship.

Pope Leo IX welcomed Macbeth to the Vatican

Pope Leo IX welcomed Macbeth to the Vatican

In a further sign that Scotland was open to international business, Macbeth’s reign also saw the first mention of Normans in Scotland when he took two into his service in 1052. Having left Edward the Confessor, two knights, Osbern and Hugh, joined Macbeth’s military council. Unfortunately, their impact in campaigns in opposition to the Normans’ reputation for military prowess was negligible and they were killed at Dunsinane. This was the beginning of trouble on Macbeth’s southern borders.

The battle, as in the play, saw a massive, well-equipped army march north from England led by Siward, the powerful Earl of Northumbria. While Birnam Wood did not uproot itself, as Shakespeare artfully put it, some 3,000 Scots and 1,500 English lay dead at the end of the day — a massive butcher’s bill for the era.

Although he survived the fight, Macbeth’s kingdom had a chunk taken out of it as Siward crowned Duncan’s exiled heir as king of Strathclyde. The death of Siward a year later must have filled Macbeth with hope, but this would be short lived.

Malcolm Canmore, the future Malcolm III, was seeking revenge for his father’s death and had his eyes set on the crown. He marched into Scotland in 1057 and surprised Macbeth and his men at Lumphanan in Aberdeenshire. He may have come from Orkney as he was married to Thorfinn the Mighty’s widow, whose past conflicts with Moray would see no love lost between the two. Macbeth’s enemies were uniting against him.

With his forces Malcolm cornered Macbeth at Lumphanan and after a fierce fight saw the former fall on the battlefield. It seems fitting that Macbeth’s death came by the sword of Duncan I’s son, the child of the very man he killed to take the crown. Perhaps this overwhelming sense of poetic justice is what convinced Shakespeare to choose just this king to write his play about.

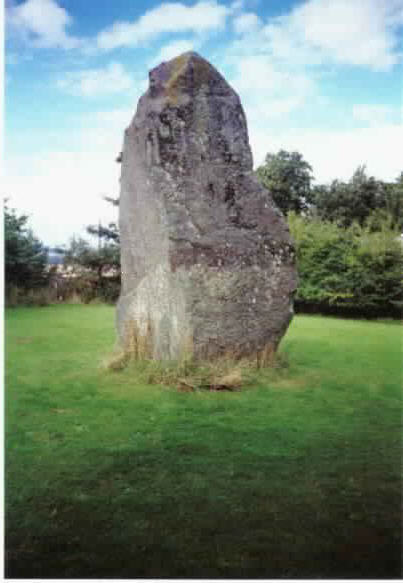

‘Macbeth’s Stone’ in Lumphanan village is said to be where the ruthless ruler was killed

But Malcolm didn’t take the throne straight away. Lulach, Macbeth’s stepson with the noble heritage, was taken to Scone by loyal followers and crowned king after his stepfather. However, the reign of Lulach — known as ‘the Unlucky’ or by less generous chroniclers, ‘the Idiot’ — was destined to be short-lived, as just four months later Malcolm would slay him at Essie in 1058 and take the throne as Malcolm III.

However, Medieval Scottish history is murky. An alternative tale sees Lulach and Malcolm combine their forces to take vengeance on Macbeth, the man who had killed both their fathers. After his death, Malcolm may have then rounded on his ally and taken the throne for himself. Whatever the actions, Malcolm III emerged victorious and ended Macbeth’s line for good.

Macbeth’s actions were not unusual for a Scottish king in this era of blood and strife, but his story is certainly made all the more famous as a result of Shakespeare’s dramatic attentions. While not the tyrant portrayed in the play, Macbeth claimed the throne through ruthless force, carving out a reign in a bloody and turbulent time in Scottish history.

We get a feel that Macbeth was a capable ruler and a man of ambition, taking revenge against his father’s killers to rule Moray by exploiting the political stage and using his military might to take the Scottish throne. While he was able to rule with impunity for a number of years, the feuds created by his actions came back to haunt him and he died at the hands of men hellbent on revenge.

This article first appeared in All About History issue 58. Buy the new issue here or subscribe now.