My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

– Percy Bysshe Shelley, ‘Ozymandias’ (1818)

Antiquities had been brought from Egypt to Europe in the aftermath of Napoleon’s invasion of 1798–1801 (one of the results of which was the extraordinary career of Jean-François Champollion, ‘Father of Egyptology’ and first European to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs), and just as Egypt began the 19th Century under Napoleonic yoke, it would end it as the pith helmeted possession of Great Britain. In the decades between, an Anglo-Egyptian effort resulted in the Suez Canal (completed 1869) – the vital artery of Empire that placed the adjoining land firmly within the foreign policy orbit of Britain and saw the Nile flood into public life.

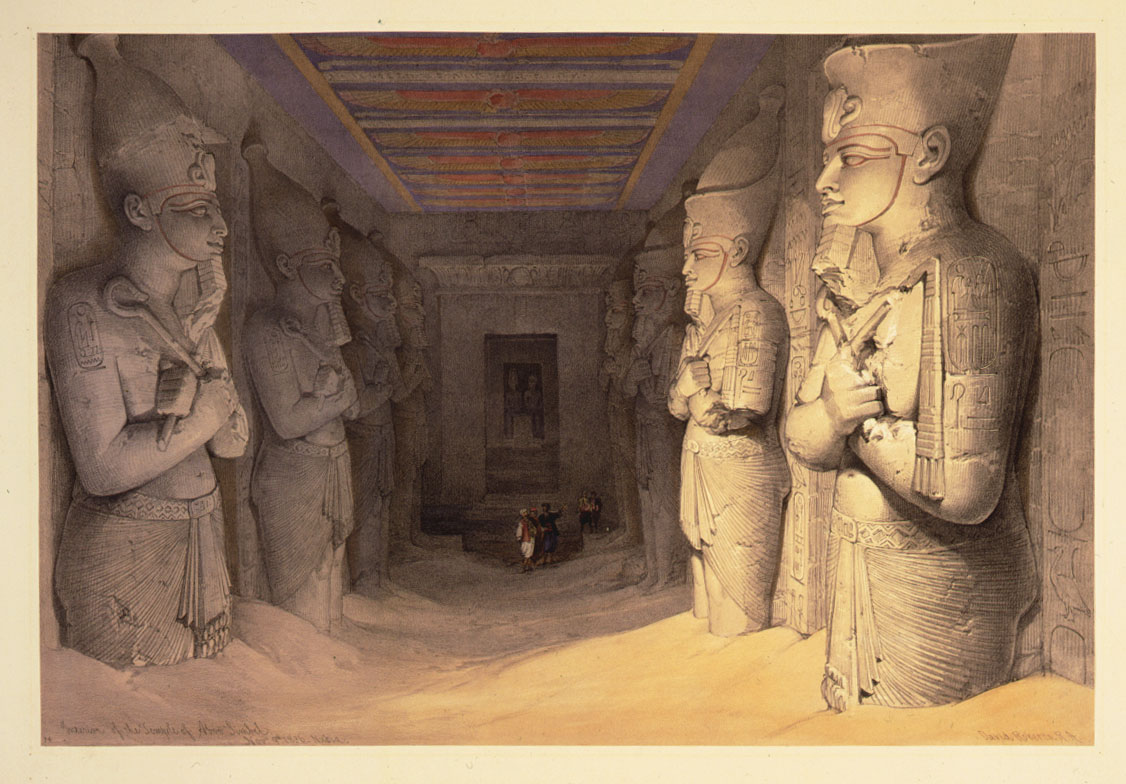

Capturing the spirit of these early decades, romantic poets Percy Bysshe Shelley and Horace Smith released competing versions of Ozymandias (1818), a Greek name for Ramesses II, that pondered on the lost majesty of the pharaohs, just as adventurers and glory-hounds competed to strip Egypt of its heritage. Letters filled the newspapers arguing that Britain had a duty to gobble as many relics, remains, mummies and masonry as was humanly possible, and Georg Ebers frothed imperiously in his two-volume Egypt: Descriptive, Historical, and Picturesque (1878) that:

Everyone, high and low, has heard of Egypt and its primeval wonders. The child knows the names of the good and the wicked pharaohs before it has learned those of the princes of its own country.

These “primeval wonders” found new homes in Britain, France, Italy, Germany and the United States of America. Naturally, the Victorians were very curious about Egyptian mummies, but as the early part of the century began to fade these concealed corpses became objects of increased interest as the Enlightenment Egyptomania of Champollion and his peers gave way to morbid fascination and fear, driven by the 40-year mourning of Queen Victoria, costly wars in South Africa and Crimea (to name but two), and neuroses about an ascendant British Empire that defied the gods and desecrated the god-kings in its conquest of Egypt.

Egyptian Revival Monuments and Mourning

While cheerier souls toyed with Ancient Egyptian motifs in soft furnishings, architectural follies and advertising (Oscar Wilde echoed the sensues, decadent Egypt of the soaps and cigars with The Sphinx in 1894), many saw something in Valley of the Kings that struck a clear tone with their darkest desires. Ancient Egyptians believed in giving their dead an appropriate send-off, constructing elaborate mausolea to them, and entombing their corpses with personal possessions that might assist them in the afterlife.

For the Victorians, with their equally morbid and complex mourning rituals, the example of these ancient people was one to follow – perhaps they even saw something of themselves in this ancient empire, its ambition, wealth and grandeur, and saw its collapse as a potent reminded that even the greatness of Britain will one day fall to dust, just as Champollion’s beloved Napoleon had done.

Throughout the 19th century, Egyptian influences could be found in women’s mourning jewellery, which often featured obelisks or scarabs (even real scarabs, with desiccated beetles being a perfectly regular fixture on earrings), and on tombs, mausolea, cemetery gates and even entire graveyards, which had an Egyptian style of architecture or decorative features. Most prominent of these is London’s Highgate Cemetery, with the Egyptian Avenue and the sunken Circle of Lebanon added by James Bunstone Bunning between 1839 and 1842.

It became a tourist attraction almost instantly and its otherworldly atmosphere was part of the allure, as William Justyne wrote in his 1865 Guide to Highgate Cemetery:

As we enter the massive portals, and hear the echo of our footsteps intruding on the awful silence of this cold, stony death-palace, we might almost fancy ourselves trading through the mysterious corridors of an Egyptian temple.

Mummy Unwrapping and Mummy Wheat

At the start of the era, surgeon Thomas Pettigrew began organising public events where people could go to watch mummies being unwrapped. However, these cod-scientific displays were, in reality, more about playing on people’s desire to be scared and entertained in equal measure. Pettigrew would saw off parts of the mummy’s skull, showing how the brains had been removed, and, for his big finale, would raise the mummy to its feet, as though it was still alive.

The Morning Post of 8 April 1833 recalled almost breathlessly:

The general interest now became very great, and every step was watched with the utmost curiosity. [….] During Mr Pettigrew’s various remarks and his unravelling of the mummy there were frequent strong expressions of the great satisfaction and gratification which he had afforded.

Such events continued throughout the century with ‘mummy unwrappings’ as particularly gristly social events becoming almost routine – Pettigrew alone was estimated to have conducted around 40 unwrappings personally. An addendum to the topic came in the form of ‘mummy wheat’ (alongside ‘mummy peas’ and ‘mummy bulbs’) grown from seeds found in the mummy’s bandages – or clutched in its dead hands – and implausibly believed to be from the time of the Pharaohs.

Where the seeds actually came from is uncertain, with Pettigrew often cited as the source in correspondence between the well-to-do. Periodicals were filled with accounts of ‘ancient’ cobs of corn being successfully grown. Martin Tupper, the unofficial hype man of the phenomena who wrote numerous letters to The Times about his fool’s harvest and even presented corn to Prince Albert, wrote a particular strenuous poem, On A Bulbous Root (Which Blossomed, After Having Lain For Ages In The Hand Of An Egyptian Mummy), in which he ponders excruciatingly on the grain’s dreamless sleep:

What, wide awake, sweet stranger, wide awake?

And laughing coyly at an English sun,

And blessing him with smiles for having thaw’d

Thine icy chain, for having woke thee gently

From thy long slumber of three thousand years?

Incredibly, this was taken very seriously by learned folk of the day, attracting much interest from the Royal Society.

In 1852 Pettigrew gave back to the field he had so gleefully appropriated by embalming the body of the 10th Duke of Hamilton in strict recreation of Ancient Egyptian methods. The Duke’s mummified remains were placed in Ancient Egyptian sarcophagus he had purchased 30 years earlier (and chiselled out to fit his frame). This folly didn’t end there and his grace was entombed in a vast Roman-style mausoleum on the grounds of his Scottish estate, described by The Times as:

“The most costly and magnificent temple for the reception of the dead in the world – always excepting the pyramids.”

Ancient Curses and Ritual Magic

German Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius produced the first modern translation of scattered Ancient Egyptian literature relating to funeral customs, bundled together as the Book of the Dead in the 1840s and erroneously believed to be an authentically Egyptian holy book in itself. This volume detailed Ancient Egyptian beliefs about death and the afterlife, the terrible trials awaiting the deceased in the worlds beyond ours, and the curses and charms by which they could stand a fighting chance of passing on unscathed.

The Freemasons had made use of Egyptian imagery and philosophy in their rituals since the late 18th Century as a way of setting out their own legitimacy and inventing an unbroken sense of heritage, but in tandem with Egyptomania – and in opposition to the Christian lens through which matters of life and death were being viewed – Russian-born occultist and fraud Helena Blavatsky jumbled together emerging theories and fictions in Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology (1877).

Blavatsky’s writing – along with further editions of the Book of the Dead that espoused now discredited views about death cults – became linked to the foundation of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in, an influential circle of occultists and pipe-tapping seekers of mystery whose members included (or were rumoured to include) WB Yeats, Arthur Conan Doyle, Algernon Blackwood, and, eventually, the Edwardian era’s ‘Wickest Man in the World’ Aleister Crowley.

The Golden Dawn took Blavatsky’s writing and ran with it, forming pseudo-Egyptian temples and cloaking their rituals (which drew from Ancient Greek philosophy, the writings of John Dee and the Hebrew Kabbalah) in pharaonic set dressing. From the ground up, they presented themselves as heirs to an ancient magical tradition, enthusiastically devouring Egyptology and repurposing it for their own rites, both feeding on the popular mystique of Egypt and perpetuating it.

For the first time too, thanks to Champollion’s work earlier in the 19th Century inscriptions could be deciphered on tombs to reveal curses and age-old superstitions about pestering the departed took on a renewed urgency as grave robbers discovered themselves threatened with otherworldly retribution.

While the best known case – the discovery of Tutankhamun in 1922 and the tragic fates awaiting Lord Carnarvon and Howard Carter (which Sherlock Holmes writer Arthur Conan Doyle believed were caused by “elementals”) – are firmly Edwardian, tales of this type were circulating in the preceding decades. One account published in the Hampshire Telegraph in 1896 explains how a mummy was purchased by adventurer Herbert Ingram from the British Consul in Luxor, and promptly sent home:

The mummy was that of a priest of Thetis and it bore a mysterious inscription [….] which was long and blood-curdling. It set forth that whosoever disturbed the body of this priest should himself be deprived of decent burial; he would meet with a violent death, and his mangled remains would be ‘carried down by a rush of waters to the sea’

While hunting in Somaliland (now Somalia), Ingram was gored and trampled by an elephant who remained at the scene. By the time his companions were able to reach his remains days later all but a handful of bones had been washed away by the rains.

This captivated not just the press, but the gossips in Britain’s far-flung colonial smoking rooms and was gleefully recounted by a young Rudyard Kipling in a letter to H. Rider Haggard, author of colonial adventure fiction. Mummies feature heavily in Haggard’s work – notably in King Solomon’s Mines (1885) and She (1886) – and the author was reported to own one, purchased for him by his brother in the 1860s. A voracious consumer of Egyptology and supporter of research, Haggard was a subscriber to the prestigious Egypt Exploration Fund and dedicated one of his many works explicitly about Ancient Egypt, Moon of Israel (1918), to “Sir Gaston Maspero, K.C.M.G., Director of the Cairo Museum.”

Haggard was deeply respectful of the power of the long dead Egyptians (in part because he believed in reincarnation, claiming to have lived as one in a past life) and cautioned Daily Mail readers against defiling the dead in 1904, with an oblique reference to their reanimation:

It does indeed seem wrong that people with whome it was the first article of religion that their mortal remains should lie undisturbed until the Day of Resurrection should be hauled forth, stripped and broken up […] If one puts the question to those engaged in excavation, the answer is a shrug of the shoulders and a remark to the effect that they died a long while ago. But what is time to the dead? To them, waking or sleeping, ten thousand years or a nap after dinner must be one and the same thing.

The Mummy and Gothic Horror

Fittingly, it was Haggad who was the first to warn in fiction of the mummy’s revenge. Cleopatra: Being an Account of the Fall and Vengeance of Harmachis (1889) in which the Ptolemiac queen disturbs the remains of an earlier dynasty, a mummy called either “called Bek-Ran or Bek-Ranef” and is punished by her hubris by the long-dead spirit and a cult sworn to overthrown her ‘foreign’ dynasty.

A potent reminder not just of the perils of disrespecting the dead, but of British heavy-handedness in North Africa, this potent cocktail had been years in the making.

Shakespeare’s tragic Antony and Cleopatra (1607) with its doomed romance and decadence, Abbé Jean Terrasson’s esoteric and purportedly factual (it was anything but) The Life of Sethos, Taken from Private Memoirs of the Ancient Egyptians (1731) with its cult of Isis and Osiris, inspiring Morzart’s Thamos, King of Egypt (circa 1780) established Ancient Egypt as a world of mystery and magic, but the gruesome immediacy of mummy unwrappings, the glimpses into funerary rites provided by Lepsius’ translations, and the ‘real’ horror stories in the penny press brought it crashing home.

No longer constrained by time and by death, it brought long-dead pharaohs into the present and introduced the well-bedded, opium-fogged trope of Orientalism and that archetypal Victorian preoccupation with death to newly emerging anxieties about empire and ethnicity.

Perhaps the best known exhibit is Bram Stoker’s Jewel of the Seven Stars (1903) – second in his canon to the infinitely more celebrated Dracula (1897) – and Stroker read widely around Egyptology across the 1880s (and corresponded with Oscar Wilde’s father, noted collector of cadavers Sir William Wilde), but he wasn’t the first to crack the seal on the tomb.

The Mummy!: Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century (1827) by Jane Webb is widely credited as the first “mummy” story (if you want to make a subgenre of it). Inspired by mummy unwrappings and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), it is a breed apart – an idiosyncratic piece of science fiction horror that seems to have inspired few imitators beyond Edgar Allan Poe, who broke from his frantic prose for a short comic offering, Some Words with a Mummy (1850).

Inspired by the rustling scandal of the popular press, gothic horror would arrive in the long shadow of the pyramids with a furious barrage of output in the 1890s. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s short-stories Lot No. 249 (1892) and The Ring of Thoth (1890), Guy Boothby’s Pharos, the Egyptian (1898), and Richard Marsh’s The Beetle (1897), which outsold Dracula on its release and was turned into a silent film in 1919, all dealt with immortal beings (sometimes mummies, sometimes more fanciful still) and their often deadly interactions with the living.

Their motivation being most often revenge for ancient wrongs or disturbed burial places, as Boothby’s titular fiend explained:

“Ah, my 19th Century friend, your father stole me from the land of my birth, and from the resting place the gods decreed for me; but beware, for retribution is pursuing you, and is even now close upon your heels.”

While Universal’s 1932 horror movie The Mummy isn’t based directly on any one volume of bandage-tugging fright, the pulp pioneers of the 1890s set down the codes that brought Karloff’s cadaver back to life, inspiring a cinema icon that has rarely been off screen since.

Egyptian Hall and the Spiritualists

This link between fear, entertainment and science, with its specific Egyptian focus, was highlighted by the presence of the Egyptian Hall in London’s Piccadilly – an elaborate, all-star conclusion to the dark side of Victorian Egyptomania.

Built in a thunderously over the top “Egyptian style” in 1812 (a similar structure can still be seen in Penzance, of all places), it was originally a museum designed to house curiosities from Captain Cook’s adventures the South Seas, but by the late 1800s it was associated with séances, theatre and magic shows – consistent with the general trend toward spookiness, from the curious and enlightened 1820s to the morbidly fascinated 1880s. Indeed, the ‘Vanishing Lady’ trick was believed to have made its British debut at Egyptian Hall and took on a localised form inspired by H Rider Haggard’s She. Inspired by the climax of the novel where the Egyptian queen Ayesha enters a pillar of fire and is reduced to cinders, the ‘Cremated Lady’ makes the return journey too via a trap door behind a curtain.

It wasn’t all escapist chicanery, though. Openly dismissive of spiritualism, where cynical charlatans deployed diversions and conjuring tricks to simulate the arrive of spirits and stimulate the emptying of purses and wallets, in-house duo of Maskelyne and Cooke conducted openly fake séances and hauntings with a view to underscoring how easily it could be done.

John Nevil Maskelyne probably wondered why he bothered. So skilful were the pair’s recreations, he moaned, that:

“…the Spiritualists had no alternative but to claim us as the most powerful spirit mediums who found it more profitable to deny the assistance of spirits.”

In a world that was advancing at an unprecedented pace – where steam trains carved a path through the countryside and suspension bridges loomed large on the landscape – the Victorian era was also a golden age of belief. Sentimentality, superstition, spiritualism and magic pervaded every aspect of daily life, from literature and architecture, to fashion and social etiquette.

It seemed that for every rational action, was an irrational reaction and the cold light of reason met its match in the red light of Amun-Ra.

For more on Ancient Egypt, pick up the new issue of All About History or subscribe now and save 25% off the cover price.

Sources:

- Mummies around the World: An Encyclopedia of Mummies in History, Religion, and Popular Culture by Matt Cardin

- Reading the Sphinx: Ancient Egypt in Nineteenth-Century Literary Culture by L Parramore

- The Mummy’s Curse: The True History of a Dark Fantasy by Roger Luckhurst

- Egypt Land: Race and Nineteenth-Century American Egyptomania by Scott Trafton

- Bram Stoker, Dracula and the Victorian Gothic Stage by C Wynne

- https://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/research/directory/material_culture_wengrow/Gabriel_Moshenska.pdf

- https://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/undergraduate/modules/fulllist/special/endsandbeginnings/bulfinonmarsh.pdf

- http://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2859&context=theses