From sandcastles to fish and chips, promenades to pleasure piers, many of the things best associated with a trip to the British seaside have their roots in the Victorian summer holiday. However, while we take these seaside attractions for granted now – even looking back on them as old fashioned – many of them were considered revolutionary at the time, some even an affront to common decency. This led to some puritanical restrictions, but not even Victorian morality could hold back the tide of change that was rolling in.

Peacocking on the prom

Trips to the seaside were nothing new at the beginning of the Victorian era, at least for the upper classes. In fact, ‘taking the waters’ for your health was so popular during the Georgian period that Jane Austen featured both the spa town of Bath in two of her novels and the coastal town of Lyme Regis in Persuasion. As Austen was keen to point out, while these trips were ostensibly about getting fresh air and exercise, they were also often an excuse for high society to mingle and show off. As well as prove that they could afford not to work, they could also stay at grand hotels, attend the theatre, and wear the latest fashions at parties.

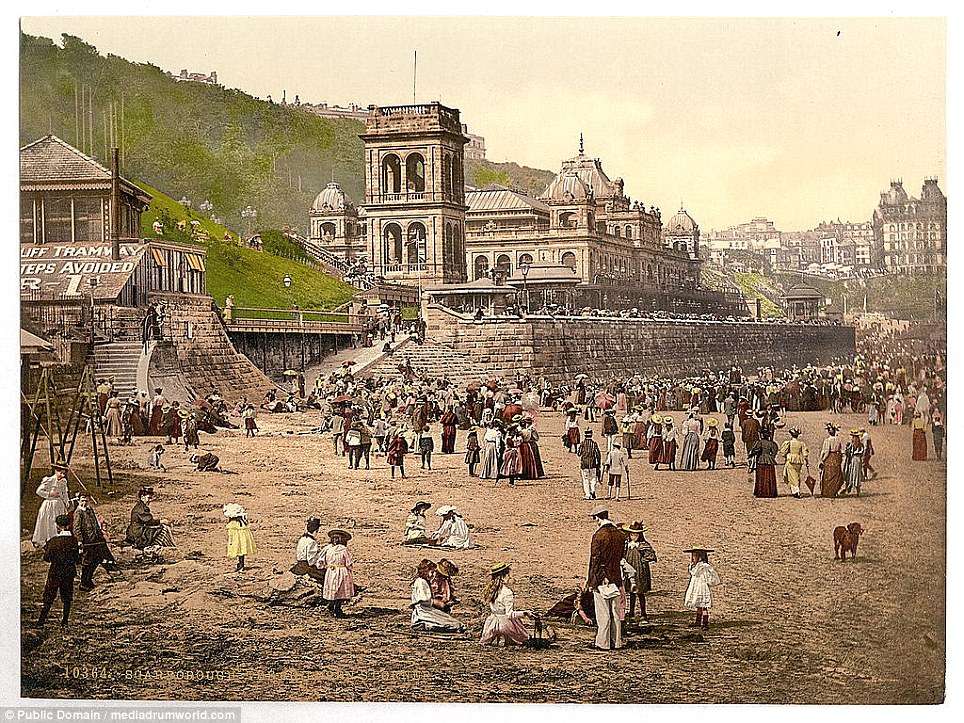

A classic example of this exhibitionism masquerading as healthy living was promenading. A stroll along the seafront was considered good for the constitution, but a long, level ‘prom’ or esplanade was also like a public catwalk where you could be ‘seen’ by society and enjoy admiring glances as you strolled serenely by, decked out in your best attire. Promenading only grew in popularity during the Victorian era, with the first piers being built in the 1850s to give tourists somewhere to stroll as well as to moor ships. While spa towns like Bath and Harrogate still held their appeal during Queen Victoria’s reign, doctors were increasingly recommending trips to seaside resorts. This was mainly because they believed that the bracing sea air contained what they termed as ‘ozone’ or ‘activated oxygen’, something that was “very essential but also a preventative of disease and a great aid for the treatment of ailments of all character.”

Prince Albert, a staunch advocate of science and healthy living, led by example by building a new royal residence by the sea in 1845: Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. The royal family spent many summers from July to August at their palatial holiday home, with Queen Victoria continuing to stay there regularly long after Albert died in 1861. We now know that the Victorians were quite wrong about the seaside offering so-called activated oxygen. But in an era of rapidly industrialising towns and cities, it’s likely that these coastal towns offered a welcome break from the choking pollution. But the smog-ridden Industrial Revolution also brought railways. This new mode of transport could whisk you across the country in a matter of hours, shrinking time itself and opening up a whole new world of endless opportunities of how people could spend their precious leisure time. Although expensive, the burgeoning Victorian middle class could afford rail fares and were keen to follow en masse where the aristocrats led.

All aboard the bathing machines

Up until the 1850s, it was not unusual for men to bathe or even swim in the sea completely naked. But such a tradition would not fit with the ever-expanding popularity of the seaside holiday. Not only were there more people sharing the beach, many of them were now women and children. Victorian values and correctness dictated that the proper etiquette was followed. For example, as popular as promenading was, an unmarried woman was chaperoned by a married lady – a family member or friend – when strolling to ensure that the strict social boundaries between the sexes were not crossed and to ward off any unwanted or unsavoury advances. On the beach, this became something of a nightmare for Victorian decency, especially when it came to the tricky subject of bathing in the sea.

Promoted as a healthy pastime, sea bathing was as popular with Victorian women as men, if not more so as it represented another small yet significant change in attitudes towards what women should and should not do. It is important to point out, however, that it was bathing in the sea that was the draw – swimming in open water was quite rare. Paddling and dipping were both thought to invigorate health, but the big question was how could men and women benefit from such pleasurable pursuits while maintaining the essential Victorian decorum?

The first solution was quite straightforward – men and women would bathe in separate parts of the beach. In 1847, Parliament gave local councils new powers to set how far apart the sexes had to be when bathing. One such by-law passed by Lowecroft, Suffolk, which was not unusual for the era, dictated: ”A person of the female sex shall not, while bathing, approach within 100 yards of any place at which any person of the male sex, above the age of 12 years, may be set down for the purpose of bathing.”

Regulation also required that women wore a “suitable gown or other sufficient dress or covering to prevent indecent exposure of the body.” This swimwear could be extremely heavy; sometimes weights were even sown into it, so that dresses did not float to the surface. In choppy waters, these heavy outfits could drown a wearer. But these coveralls did serve another purpose: they stopped the ladies getting a suntan. Until the 1920s, having a tan was considered vulgar and only for workers in the fields. On the beach, parasols would also be employed to shade them from the sun. However, as modest as Victorian swimwear was, to their prudish minds, a woman having to walk the length of the beach to the sea – even on a gender-segregated beach – was the equivalent of a modern ‘walk of shame’. Instead, they used a bathing machine.

Strictly speaking, bathing machines dated back to around the 1750s and were not really ‘machines’. Resembling a beach hut with four wheels, it would be rolled out to sea, usually pulled by horses. Some machines were equipped with a canvas tent around the doorway, capable of being lowered to the water and thus giving the bather greater privacy. Once deep enough in the surf, the bather would then exit the cart using the door facing away from prying eyes on the beach and proceed to paddle. For inexperienced swimmers – which would have been most Victorian women in their billowing swimwear – some beach resorts offered the service of a ‘dipper’, a strong woman who would escort the bather out to sea in the cart and lift them into the water and yank them out when they were done. When the swimmer wanted the bathing machine brought back in, they would signal the operator by raising a small flag attached to the contraption’s roof.

Bathing machines were deeply hypocritical. Men did not have to employ any similar device and they just strolled into the water wearing a considerably tighter swimsuit. But in a strange sort of way, bathing machines also played a small part in giving a modicum of freedom to Victorian women, allowing them the privacy to experience sea bathing first-hand rather than be excluded altogether as they had been from so many other leisure activities and sports.

Another addition to the crowds that set the seaside holiday apart from anything that had gone before were children. Depending on class and standing in the world, Victorian children were either the educated future of the family line or just another worker, toiling in appalling conditions. But with rising prosperity came more disposable income and the ability to spend some time together as a family at the seaside. Those who once could only look on in admiration from afar as their ‘betters’ enjoyed a seaside break were now able to taste it for themselves.

As access to the seaside increased, many organised trips through churches, charities and societies such as the Temperance Movement gave opportunities to even the lowest in society. 1871 saw the introduction of the Bank Holidays Act that set aside four days through the year as official holidays for all for the first time. These were not paid – an entitlement to paid holiday would not become law until the 20th century – but with ever-improving transport links and the cost of an excursion subsidised by groups and organisations, the nature of the seaside holiday began to change dramatically both in its scale and its experience.

Resorts boom

The railways transformed small communities – which often started as mere fishing villages – into bustling resorts to which people flocked in growing numbers. By the middle of the 19th century, towns such as Brighton had already expanded, numbering 44,000 in the 1841 census. Other popular resorts like Blackpool and Llandudno had started much smaller, but with the industrial centres of Manchester and the Midlands not far away, they rapidly turned into the must-go places for groups of friends and co-workers looking for a few hours of fun.

In response to such high demand and the ability of some holidaymakers to even stay for a night or two, accommodation became a valuable commodity. A range of boarding houses and hotels sprang up to suit every budget. Resorts that regarded themselves as catering for the better class of person – places like Brighton with its royal links to the Georgian era and Ryde on the Isle of Wight, with its proximity to Queen Victoria’s Osborne House – tended to already have large, grand hotels as close to the seafront as possible. But for Blackpool and similar destinations, the lack of deeply rooted tradition meant they had more freedom and could virtually start from scratch. Boarding houses and small hotels became booming businesses, but one rule applied no matter where you stayed: the closer to the sea, the higher the price. And unscrupulous landlords were always looking for ways of extracting as much out of people’s pockets as they could by whatever means necessary – especially what was meant by a ‘sea view’!

With the development of the resorts came the expansion of the wealth of the towns and what they were able to offer in entertainment for holidaymakers to spend their money on. In many cases, the local pier would be extended to become even more impressive, offering a greater variety of entertainment than before. Building was sometimes on a grand scale, with the creation of much more indoor entertainment to combat the unpredictable British weather. Aquariums, amusement arcades, ballrooms and even circuses were constructed as permanent fixtures to keep the public entertained and keep them spending.

With typical Victorian enterprise and invention, technology and mechanisation had their parts to play. Electric lighting illuminated the promenade, steam carousels and fairground rides appeared on the prom and the pier. Competing resorts made bold statements to attract customers, and what better way than with a replica of the Eiffel Tower at Blackpool to embody a sense of pride and success? The beach had not been forgotten – it was now just part of the whole drama and no longer the main character. What had been created for the seaside break was more choice and less reason to leave.

From rather sedate, genteel beginnings at the start of the Victorian age, by the end of the 19th century things were starting to look somewhat different. As the era progressed, so did the resorts, expanding not only in size but in what they had to offer. Demand drove innovation not only in the construction of new entertainments but also in transport, with rapid improvement of the railway network to help quench the ever-popular thirst to get away from it all. People from all walks of life now shared the experience and attitudes, and standards slowly started to change. Many traditional ladies would still not take a dip in the sea, but for a younger, more liberal generation, it was a release from the strict ties of social boundaries that they fully embraced. Ladies’ swimwear become slightly less restrictive and more risqué; the sexes mixed openly on the prom; bawdy ‘what the butler saw’ machines appeared in the arcades; and comedians told rude jokes in the music halls.

Tired of increasingly having to mix with the hoi polloi, the upper classes began to abandon their traditional resorts. Instead they spent their time and money on foreign holidays where, for now at least, the masses could not follow. What was

left were the majority who had learned how to relax and enjoy themselves, willing and able to spend their hard-earned cash on a dazzling array of entertainments. It was the working man and his family who had taken ownership of the seaside holiday. With ever-improving conditions for workers, the popularity of what the Victorians created continued to rise, leaving a legacy that still rings true today – and it is them we must thank that even now we all still love to be beside the seaside.

This article first appeared in All About History 55. Discover the latest issue of All About History here or subscribe now.