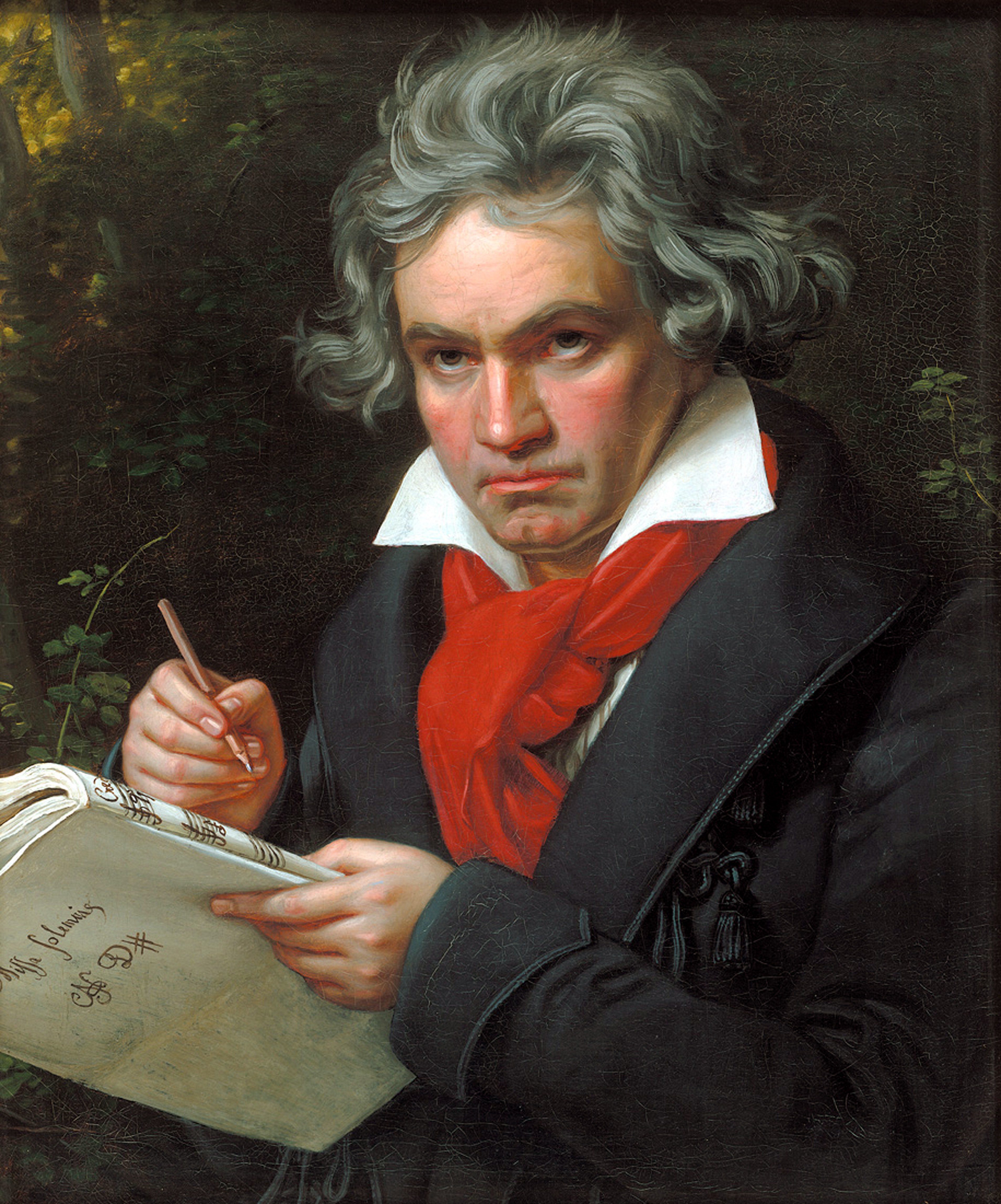

Ludwig van Beethoven is one of the most famous and influential of all composers. His best-known compositions include nine symphonies, five piano concertos, one violin concerto, 32 piano sonatas, 16 string quartets, his great Mass the Missa solemnis, and one opera, Fidelio.

You probably know that already, but here are seven facts about Beethoven that you may not know:

1. He had secret children

Frantic in 1820, and fearing he would lose his adopted nephew, Karl, Beethoven drafted a 48-page memorandum for the court, detailing all he had done for his nephew and attacking Karl’s mother, Johanna.

Vienna was divided, many supporting the mother in her struggle for her child. Few realised that Beethoven was fighting for the last soul he could call his own, as no one knew of his illicit fatherhood of Karl Josef.

Johanna became pregnant again, giving birth to a daughter at the end of that year. She named her child Ludovica – the female form of Ludwig. The public may have belittled him, but they still tried to ride on his fame.

2. He handled heartbreak with laundry

Josephine Deym, the young widowed mother to whom Beethoven wrote a series of letters between 1804 and 1807, warmed to his advances at first. However, her family intervened: Ludwig was too poor, he was not noble, and he might not be able to support himself in his deafness, let alone her and her children. She claimed he was pressing his ‘sensuous love’ too keenly. Therese Malfatti followed in 1810, Bettina Brentano later that year.

In 1817 Beethoven was heartbroken having just heard of his child’s devastating illness. From being a bright youngster, thirsty for knowledge, Karl Josef, the son he had never seen, was stricken with a mystery illness which left him confined to a wheelchair, with the mental age of a four-year old. So instead of writing music, the distraught composer wrote pages about the laundry; this missing night-shirt or that pair of socks.

He had displayed similar behaviour in 1813 after leaving his Immortal Beloved, Antonie Brentano, pregnant with his child. Her husband had taken her back to Frankfurt, bringing up Beethoven’s child amongst his own.

3. He made three re-writes of Fidelio

Beethoven’s great opera Fidelio was not an instant success. It opened in 1806, in a hall half-full of French officers from Napoleon’s army, which had just invaded Vienna. Despite revisions a year later, success for Fidelio still proved elusive.

By 1814, Beethoven was Composer in Residence at the Congress of Vienna, performing before Czars, Emperors and princes, with purses of ducats pressed into his hand. Having asked for permission to perform Fidelio, he revised it as a two-movement opera.

His librettist tells the story of Beethoven’s revised setting of the aria, beginning in Act 2, where Florestan, in his dungeon, imagines he sees his wife in the form of an angel come to his rescue. This is believed to be inspired by Beethoven’s Immortal Beloved, Antonie Brentano, the mother of his child.

4. He was caring and interfering

He played to Dorothea Ertman, at the request of her husband, to release her grief after the death of their child. ‘Now we will talk in tones.’ He played to Antonie Brentano after her father’s death, when she with her husband and family living in Vienna.

Beethoven had fisticuffs with his brother Johann when he tried to stop Johann from marrying Therese, who already had a 5-year old child by another man. Johann married her anyway. When the two brothers lived next door to each other in the mid-1820s, Therese stood behind the door with a poker, waiting to bring it down on brother-in-law. Beethoven was writing his brotherhood symphony at the time.

5. He had an extraordinary IQ

When Johann bought his estate in Gneixendorf, he signed himself in one New Year’s greeting card as: Johann van Beethoven, Land-owner. Beethoven responded with his own card: Ludwig van Beethoven, Brain-owner!

When writing his ‘greatest work,’ the Missa Solemnis, Beethoven terrified one visitor who caught him at work, face contorted, forehead bulging. The autopsy showed that Beethoven’s brain had particularly pronounced convolutions. Mensa worked out that he had an IQ of 200.

6. He was un-worldy

He elicited both concern and affection. As a young man on a Rhine cruise with the Elector’s orchestra, Beethoven took his turn in washing the pots. In later life he was followed home from a tavern by someone who feared for his safety when he seemed self-absorbed, lost to the world.

He was popular, for all his idiosyncrasies, stripping off to walk the Vienna woods in summer, unobserved, notebook in hand. Walking along a waterway, lost in thought, he was once arrested as a tramp. The Chief of Police was called, looked at the raging wild man and exclaimed, ‘But that is Beethoven!’

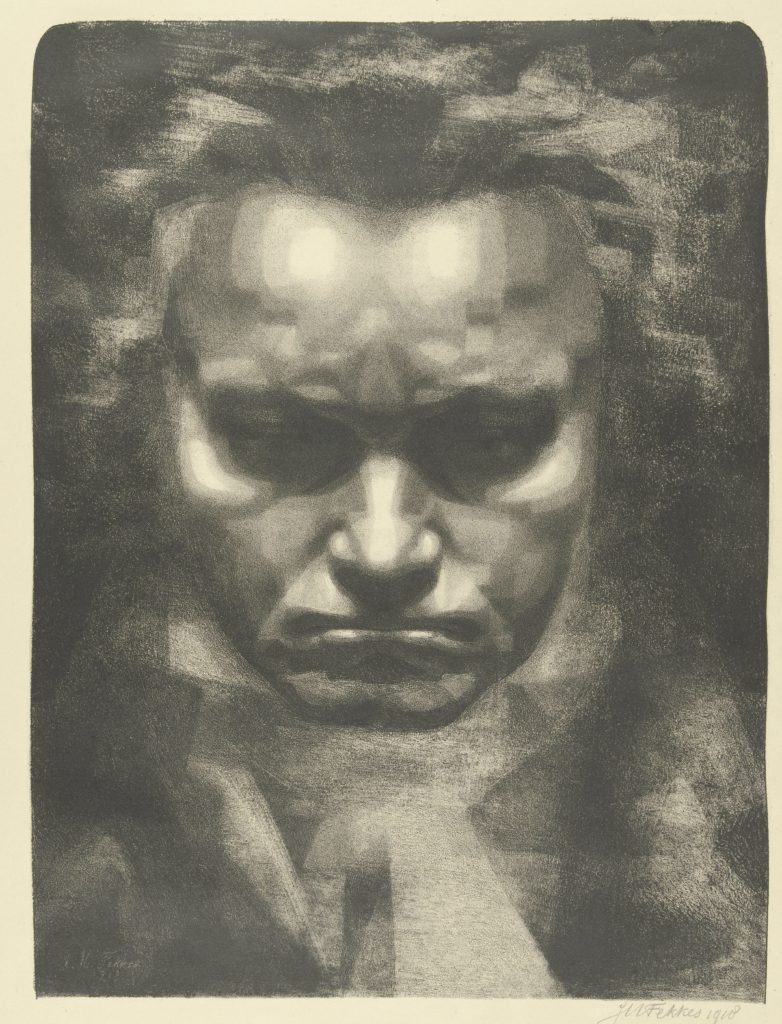

7. He was deaf

Perhaps the most astonishing yet tragic facts of Beethoven’s life was his gradual descent into deafness. There are many myths surrounding the cause of his loss of hearing, with one story even claiming the composer had a propensity for suspending his head in freezing water to keep himself awake during long nights spent composing.

In an 1801 letter to one of his close friends, he declared:

For almost two years I have ceased to attend any social functions, just because I find it impossible to say to people: I am deaf.

He later elaborated on his intense struggle with his ailment, and its impact on his mental health as well as his artistic ambition. In a document known as the Heiligenstadt Testament Ludwig discusses the crisis of his deteriorating health, his contemplation of suicide, and his resolve to endure his ailment with stoicism. The document was addressed to his two brothers, Carl and Johann, although was never sent and remained undiscovered until after Beethoven’s death in 1827.

Susan Lund is author of many books on Beethoven, including Beethoven: Life of an Artist. For more incredible lives of famous people, subscribe to All About History from as little as £2.19 per issue.