The 19th century is when the novel as we know it sprung to life, enthralling a hungry, growing audience of literate Victorians, and transforming creators into household names. But most remarkably of all, the era ushered in a wave of female pioneers, an early form of girl power which vitalised literature, and inspired feminists of the future. The genre which played a hand in this victory was the Gothic, with its surrealist form offering opportunities to explore much which could not be intimated in traditional works. Amidst the eerie castles, striking landscapes and medieval settings of the Gothic, these female writers could call into question male-dominated society, turn traditional power dynamics on their head, and use the supernatural as a vehicle for the sensual.

This isn’t to say that the genre was always empowering, as texts such as Dracula prove. With his contrasting depictions of the virtuous Mina Harker and salacious Lucy Westenra, Bram Stoker is perceived to have been assailing the ‘New Woman’ – a term describing the Victorian females who were dispensing with the barriers dictating what they could not (and should not) achieve. But although female novelists led the way in breaking new ground, this came under intense scrutiny and prejudice. Many used male aliases, criticism was levelled at their deviation from ‘feminine’ matters – Mary Shelley was described as having a “masculine mind” – and some of their families felt compelled to rewrite aspects of their characters after their deaths; for example Jane Austen’s brother Henry purposefully played down her ambitions, intentions, and knack for social critique. Nevertheless, their accomplishments were many, and their books have brought joy to generations of readers. In this bicentenary year of Emily Brontë’s birthday, and the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, discover how Gothic fiction shaped the lives of 10 talented women.

Ann Radcliffe

(1764 – 1823)

A pioneer of Gothic’s first generation

Hailed as the “Great Enchantress” and the “Shakespeare of Romance writers”, Ann Radcliffe was one of the most influential novelists of her era, and made a marked impact on the Gothic genre. Especially acclaimed for The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), Radcliffe became known for a number of innovations, including her poetic landscape prose, but particularly for her use of the ‘explained supernatural’; her tales were concluded with natural, yet complicated, explanations. Some critics felt cheated by this device, and Radcliffe dispensed with it in her final (posthumously published) novel Gaston de Blondeville (1826) – instead crafting a real ghost – but it has also been suggested that the ‘explained supernatural’ was authentically Gothic, delving into the fear of the supernatural rather than supernatural beings themselves. Radcliffe’s works – which soaked up the enlightenment values common before the French Terror – were so in demand that she was paid extraordinary sums for the final two novels published in her lifetime: £500 for The Mysteries of Udolpho and £800 for The Italian, when £80 was the average. It is impossible to say what more Radcliffe might have achieved, had she not suddenly stopped publishing aged 33, a decision thought to rest on her sensitivity to criticism.

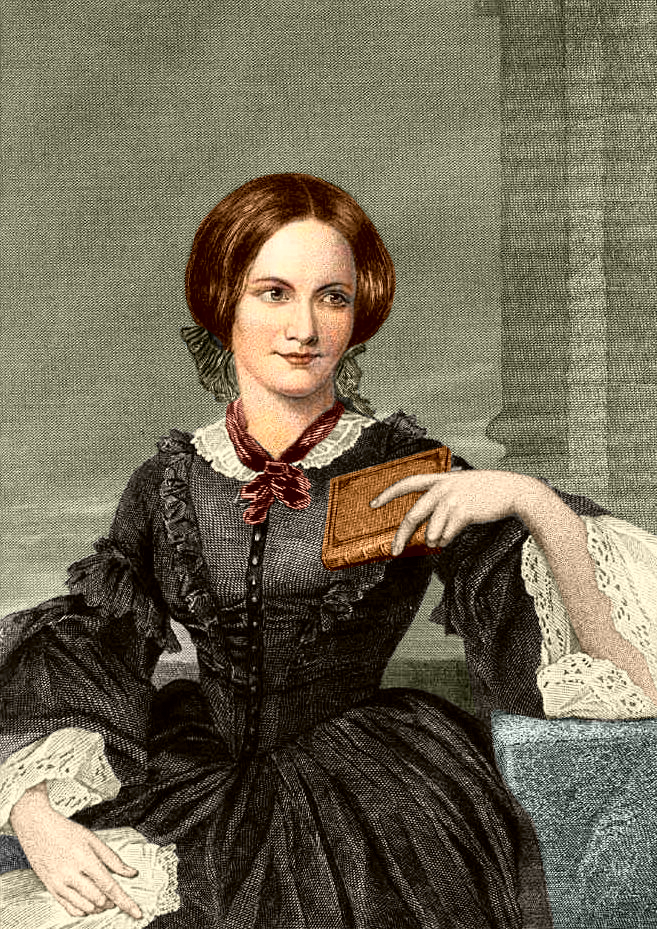

All three Bronte sisters – Anne (left), Emily (middle), and Charlotte (right) – as painted by their brother

Emily Brontë

(1818 – 1848)

Author of a classic so unique it baffled critics

Despite the emergence of new literary forms during the Victorian period, Gothic traits continued to inspire novelists. Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights begins with a nightmare experienced by narrator Lockwood, which calls to mind many essential elements of the genre. Falling asleep reading Cathy’s childhood diary – while held inside Heathcliff’s home by blizzards – Lockwood suddenly sees an icy hand reaching to him through the window, carrying the voice of Catherine Linton, pleading to be let in. This haunting episode sets the tone for the novel, and the significance of Heathcliff’s home in the text is suggestive of the Gothic narrative that historic buildings exude the stories of owners past. Wuthering Heights was the first instance in which Emily channelled her creativity into writing not just for herself but for the book-reading public, when previously her work had been only for her and younger sister Anne, their curiosities primed by an unusual – for 19th century females – childhood, sharing academic lessons with their brother Branwell. Like most female novelists of her era, including those of the Gothic tradition, Emily’s talents are appreciated far more today than they were then: contemporary critics were aghast at, and baffled by, Wuthering Heights’ wild power.

Charlotte Brontë

(1816 – 1855)

A potent blend of romance and realism changed ‘the novel’

Like sister Emily, Charlotte Brontë alluded to the Gothic in her work, and appeared to be inspired by the pioneering Ann Radcliffe. In both Jane Eyre and Villette, Charlotte depicted buildings seemingly in thrall to supernatural forces, with episodes including Jane sighting an apparition in Thornfield Hall. But in line with Radcliffe’s ‘explained supernatural’, these happenings are given logical explanations, though much fear is stirred along the way. It has been argued that Charlotte’s mix of romance and realism in Jane Eyre was her crowning success. She also demonstrated her fierce ambition, and consideration of women’s position in society, in much of her work. Confronted by the realisation that women writers were looked down on – and critiques such as the claim (by a female reviewer) that if Jane Eyre was written by a woman, it was the work of one who has “long forfeited the society of her own sex” – Charlotte strove to highlight the realities of life for 19th century women, and to also champion their rights and talents. This commitment to the cause shaped Charlotte into a proto-feminist heroine for modern women, and has helped to secure her glowing reputation, already kindled by her iconic stories.

Jane Austen

(1775 – 1817)

There was more to Austen than snapshots of gentry life

The ever popular Jane Austen is known for her witty critiques of the upper and middle classes of her time, but she was also a talented satirist of other genres. Northanger Abbey offers a clever parody of Gothic fiction, notably that of Austen’s contemporary Ann Radcliffe. Austen’s Gothic-obsessed heroine Catherine Morland supplies the humour, thanks to her courter Henry Tilney mocking the genre on the pair’s journey to Northanger Abbey, imitating Radcliffe’s The Romance of the Forest, merged with The Mysteries of Udolpho. Austen – who valued the individuality of her flawed heroines – is said to have been influenced in childhood by her family to appreciate a quick wit, and this resulted in her sharp writing. In the Quarterly Review, popular novelist Walter Scott intimated that the Gothic ‘romance’ moulded in the 1790s by himself and others, had been supplanted by tales of ordinary life, with Austen leading the charge. But he couldn’t help adding to this praise, the contrast of his fictional world to Jane’s depictions of “the middling classes of society”: “Presenting to the reader, instead of the splendid scenes of an imaginary world, a correct and striking representation of that which is daily taking place around him.”

Mary Shelley

(1797 – 1851)

The mother of Frankenstein – and science fiction

The daughter of feminist icon Mary Wollstonecraft and radical thinker William Godwin, Mary Shelley was destined for big things. Her stunning debut Frankenstein has enthralled for 200 years, and its origin – from a ghost story contest organised by Lord Byron in Geneva during 1816, ‘the year without a summer’ – has become legendary. In a “waking dream”, Shelley, then 18, saw “with shut eyes, but acute mental vision” the “pale student of the unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together”. Her vision resulted in the Romantic era’s most recognisable work, which is often credited with establishing the science fiction genre in England’s literature. Shelley utilised Gothic devices to examine the corrupt nature of power, and was among the Gothic writers of her generation to feature ‘the double’, which reached its height with Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Upon Frankenstein’s publication, critics were of the impression it was written by a man – Sir Walter Scott theorised that Mary’s husband Percy Bysshe Shelley was the thinker behind the pen – and when the novel’s true author was revealed, critics mostly ignored its politics, which examined the social, scientific and economic problems of Mary’s time.

Louisa May Alcott

(1832 – 1888)

The children’s author also explored the darker side of life

Little Women, the beloved classic which has never been out of print, was undoubtedly Louisa May Alcott’s big success, but she much preferred her work for adults, and intriguingly dabbled in Gothic fiction. Going by the name A. M. Barnard, her thrillers blended elements of madness, violence, and perversity, material deemed “unfit” for a female writer. Alcott’s work was championed by a new generation in the 1970s when these tales were rediscovered and published in the anthology Behind a Mask. As a child Alcott had acted in dramas with her sisters, and she preferred to play the “lurid” parts – “the villains, ghosts, bandits and disdainful queens”. Alcott – who had grown up in poverty – was driven by a strong social awareness. She believed in abolition, prison reform and temperance, with her main campaign centring on women’s suffrage. Alcott’s writing was arguably feminist for its time, with her most famous character Jo March known for her fierce independence and refusal to ascribe to the expectations of others as to how girls of her time should behave. Alcott was delighted about the fact that when Concord, Massachusetts allowed women to vote in local elections at the end of the 1870s, she was the first to register.

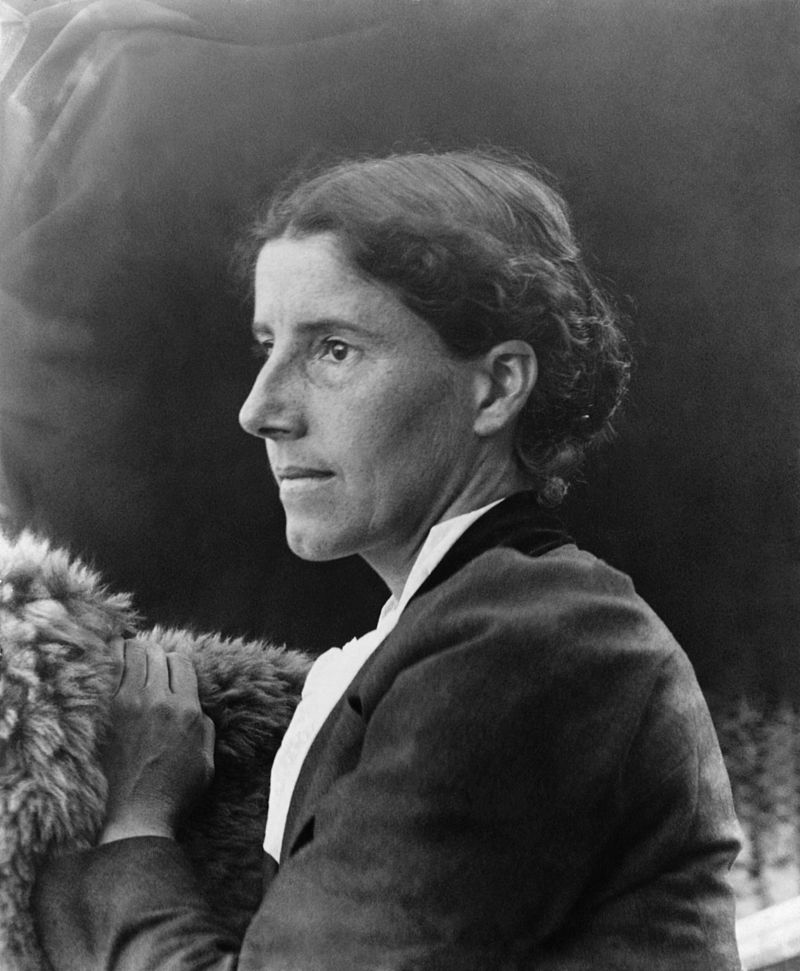

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

(1860 – 1935)

A multifaceted writer and feminist icon

Her haunting novella The Yellow Wallpaper – about a woman confined to her bedroom – draws on Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s own experience of mental illness. She suffered from postpartum depression following the birth of her daughter Katharine, and underwent the controversial ‘rest cure’, which prohibited intellectual stimulation and most exercise. Her tale features Gothic themes to explore the protagonist’s heightening distress. The room’s sense of a prison – including barred windows – links to the motif of the insane asylum, and Gilman’s language is ambiguous as to whether the events are grounded in reality or the supernatural. The movements of the “repellent” wallpaper as seen by the woman synchronise with her deterioration. Gothic ideas are also evident in the novella’s ending. Consciously reversing the Gothic scene of a heroine fainting out of terror, Gilman has her protagonist’s husband faint upon seeing his wife. Today Gilman is celebrated as an early feminist icon: she divorced her husband (sending their daughter to live with him and his second wife), and entered into a happy marriage with her first cousin; and dedicated herself to the women’s suffrage campaign. The Yellow Wallpaper’s slim size in no way diminished its stature; the novella’s message about the unrealistic domestic expectations placed on women inspired many.

Charlotte Turner Smith

(1749 – 1806)

William Wordsworth was a fan of the poet and novelist

Charlotte Turner Smith embarked on her career as a ‘gentlewoman poet’, and her success gave her the confidence to publish prose under her own name. Like Ann Radcliffe, her novels were satirised by Jane Austen in Northanger Abbey. Smith often incorporated the Gothic setting of the manor house – which has been suggested was a metaphor for the nation – and it was argued that she used the form of the courtship novel to criticise primogeniture laws. Another device was that of the ‘wanderer’ figure as a means of exploring social issues. In The Old Manor House, Orlando Somerive’s travels in America lead him to become opposed to imperialism and slavery. While, as above, Smith did later criticise slavery, she had also benefited from its existence: her husband Benjamin was the son of an East India Company director, who owned plantations in Barbados, and his and Smith’s annual income had depended on slave labour. Smith also became a vocal supporter of the French Republic, but later altered her opinion as a result of the Terror. Eventually Smith’s popularity declined, but she was remembered by William Wordsworth as “a lady to whom English verse is under greater obligations than are likely to be either acknowledged or remembered”.

Clara Reeve

(1729 – 1807)

Created the ‘literary offspring’ of Walpole’s Otranto

Clara Reeve may not be as well known as her more famous contemporaries, but she made an intriguing contribution to Gothic fiction with The Old English Baron, inspired by Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (often thought of as the first Gothic novel). The book’s preface describes it as “the literary offspring” of Otranto, likewise designed to “unite the most attractive and interesting circumstances of the ancient romance and modern novel”. The model proved popular: an eighth edition materialised in 1807, and there were many additional reprints throughout the century. Reeve grew up reading classical works on republicanism and when the French Revolution came, she welcomed the development, and made a call for change: “The revolution in France will be a standing lesson to princes and to people of all countries; it is a warning to kings, how they oppress and impoverish their people; it warns them to reform the errors and corruptions of their governments, and to prevent the necessity of a revolution.” This text foresaw an important role for women, invoking a theme of works including Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Although Reeve’s thinking here was more conservative, encouraging discipline, order, and hierarchy as in counter-revolutionary works by women.

Elizabeth Gaskell

(1810 – 1865)

Charlotte Brontë’s biographer dipped her toes into Gothic literature

Elizabeth Gaskell delved into all sorts of genres, from social commentary to Gothic. She had Gothic tales printed in Harper’s Magazine, with supernatural devices offering a means of examining themes such as power, weakness, oppression and redemption. Gaskell’s devout Unitarian faith instilled in her the social values which lay deep in the pages of her books. Mary Barton: A Story of Manchester Life (1848) was acclaimed by Charles Kingsley in Fraser’s Magazine for explaining to the middle classes Chartism: “Do they want to know why poor men, kind and sympathising as women to each other, learn to hate law and order, queen, lords and commons, country-party and corn law leagues, all alike – to hate the rich in short? Then let them read Mary Barton.” Gaskell was neither a radical nor impassioned feminist; she spoke of understanding and communication rather than drastic change. But she understood well the two lives women writers had to lead: describing the publication of Jane Eyre, she wrote: “Henceforward Charlotte Brontë’s existence becomes divided into two parallel currents – her life as Currer Bell, the author, her life as Charlotte Brontë, the woman. There were separate duties belonging to each character, not impossible, but difficult to be reconciled.”