Spread across the Mediterranean Sea in more than a thousand small city-states, the secret of the Ancient Greeks’ greatness lay in their extraordinary ambition and competitiveness

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

10. Warfare

No one had ever fought like the Greeks, and no one had ever won like Alexander the Great

The Greeks are often credited with inventing the ‘western way of war’, fighting pitched battles on foot at fixed locations until one side was defeated. This may seem ordinary enough now, but in earlier periods and other parts of the world fighting was more tentative and less bloody, more reliant on missiles, manoeuvres and displays of force. Troops were also deployed much more loosely in non-Greek armies, fighting as individuals, not a unit. Although the Greeks used cavalry and lightly armed soldiers with javelins and the like for skirmishing, the essence of Greek warfare lay in heavily armed and armoured infantry in close formation, fighting hand-to-hand to the death. This style of fighting brought a new intensity and deadliness to battles. Once it had proven decisive in international warfare, most notably against the Persians and their huge multinational armies, things would never be the same again.

The basis for this was the hoplite soldier, named after the type of shield used. Hoplites were equipped with a bronze helmet, a leather or bronze breastplate, bronze greaves on their shins, a large circular shield (the ‘hoplon’) made from leather or wood faced with bronze, a long spear made from ash and tipped with an iron or bronze blade, and a short sword, also made from iron or bronze. The armour and weapons were physically demanding for the soldiers, requiring extreme fitness.

Hoplites were also highly disciplined. They faced the enemy shoulder to shoulder in the famous phalanx formation, each man covering his companion to the left with his shield and relying on his right-hand neighbour to do the same for him. The line would always creep to the right as each soldier tried to maximise his shield protection. Each rank of the phalanx would normally be at least eight-men deep, making the pressure from the hoplite line positively fearsome.

Morale was crucial. The unprecedented horror of hoplite warfare – crushed from in front and behind, being attacked with spears and swords from close range – was psychologically demanding. If soldiers from the front line broke and ran, the battle was almost instantly lost and the fleeing army, encumbered by heavy equipment, could be slaughtered. Spirits were shored up by wine with the pre-battle breakfast, music during the advance toward the enemy, and the ‘paean’, the fearsome ululating battle cry of ‘eleleleu.’

This tactic was perfected by the Macedonian kings Phillip II and his son, Alexander III – ‘the Great’. Professional drill, greater tactical flexibility, better equipment – including the sarissa, a long pike to replace the earlier spears – and increased use of cavalry were among the factors that allowed them to first conquer Greece and then reverse centuries of Persian expansion and conquer the East in the late-4th century BCE, changing the world forever.

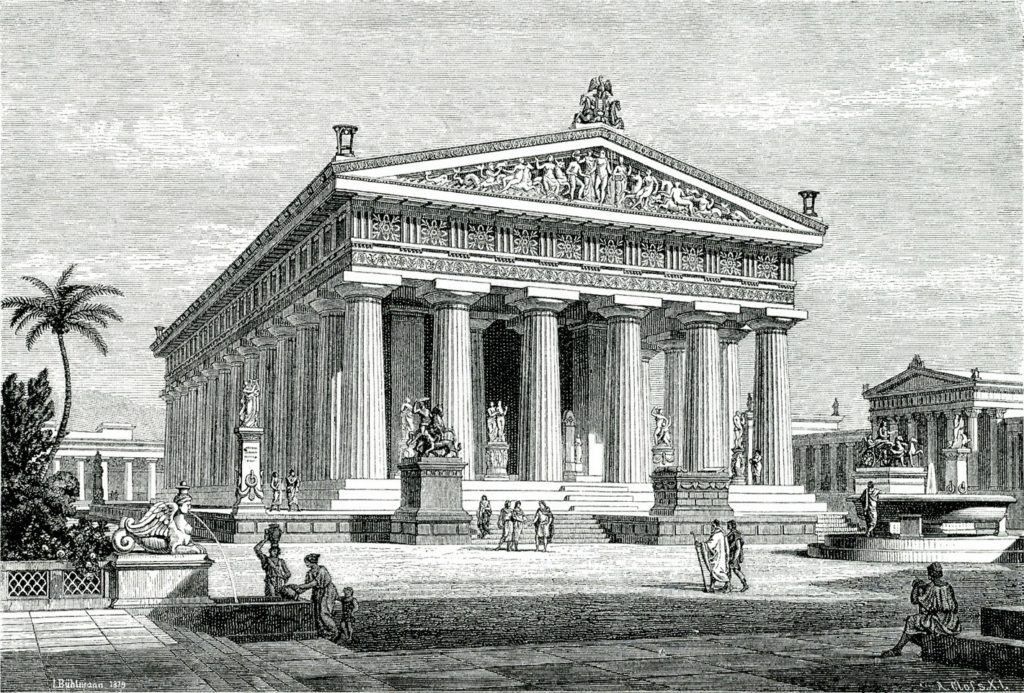

9. Architecture

We can see the influence of the Greeks in cities around the globe – our world would literally not look the same without them

Even after more than 2,000 years, Ancient Greek buildings are among the most recognisable in the world. Think of the skeletal remains on the Acropolis framed against the Athenian skyline, one of the most famous modern cityscapes. These buildings were also influential, with a huge number of public structures worldwide from the Renaissance onward being their descendants, including famous examples such as the British Museum’s façade, the Brandenburg Gate and the United States Capitol. The characteristic columns and pediments (gables, triangular sloping roofs), arranged with careful attention to symmetry and proportion, are obvious and distinctive wherever they appear; they are emblematic of the ancient Mediterranean world and its civilisation.

The legacy isn’t only physical; Greek architectural principles were the foundation for Roman and then later Western theory and practice, in particular for public architecture, while the Greeks also invented entirely new types of building, such as stadiums and theatres.

One feature of Ancient Greek architecture that didn’t survive in the originals or the later imitations was colour – the Parthenon was probably decorated in shades of red, blue and gold.

8. Politics

Before the Greeks, politics was just something people did. They made it something people thought about

Politics is a Greek word meaning ‘affairs of the polis’ – polis meant ‘city’ or ‘state’. Democracy, oligarchy, monarchy and tyranny are just some of the many other terms we have taken from them. They were probably the first civilisation to really think about politics. Unlike their contemporaries, they analysed different systems; they didn’t simply assume that their own way was the only way, even if they often thought it was the best. It was this critical thinking that was probably their greatest legacy, even more than their dramatic experiments with democracy at one end (Athens) and extreme social control at the other (Sparta).

In the 5th century BCE, the Greek world became increasingly divided, culminating in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE) in which Athens and their allies fought against Sparta and their allies. Broadly speaking, the Athenians were pro-democracy, while the Spartans favoured oligarchy – rule by an elite. While this was in some ways a straightforward power struggle, a contest between two powerful states to dominate the Greek world, it was also one of the first ideological wars. It wasn’t just a conflict between states; it was a conflict of ideals. The Spartans won and forced the Athenians to abolish democracy in favour of oligarchy, although this didn’t last and popular rule was restored.

Out-and-out monarchy was rare in Greece in the Classical period, mostly confined to border states like Macedonia. However, the future lay with the Macedonian kings, such as Alexander the Great – until these polar ideas of democracy and totalitarian rule resurfaced thousands of years later, defining large parts of the 20th century.

7. Medicine

“First do no harm,” said Hippocrates. He didn’t do a great deal of good to his patients, either, but he did lay the foundations for future medicine

The Greek contribution to scientific medicine was huge. While even the best of their doctors couldn’t cure many illnesses and they were proven wrong in many of their speculations, their ethos and method were the foundation for later developments and live on today. While supernatural diagnoses and religious and magical cures continued alongside the new rational medicine of Hippocrates in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE, this was a significant stage in the history of medicine; perhaps the single largest shift in medical thinking there has been. The new physicians said that illness had purely natural causes, coming from within the body and the physical environment; it was not a curse from gods or witches. They developed a method of close observation to study individual diseases, identifying them and cataloguing their symptoms.

Hippocrates particularly insisted on a selfless and compassionate duty of care to patients. The principles and methods were now in place to advance medical knowledge and care, even if treatment was often ineffective without today’s knowledge of physiology.

5. Sport

In Greece, the hunt for physical perfection and their extreme competitiveness created a new, everlasting spectator event…

Greek athletes were celebrities and adored to an extent that would make us blush. Winning an Olympic victory for your city would bring glory, popularity, a head start in politics if you wanted it, and even a statue. Rich citizens would compete to spend the most on preparing contestants – such as lavishing money on chariots, horses and trainers. Make no mistake, though; it was the winning that counted. Cheating and sharp practice were not unknown and could create lasting controversy and ill-feeling, while injuries and deaths were an accepted part of the fighting events. What’s more – much like now – star athletes could be persuaded to represent other, richer cities.

Although we focus on the Olympics, and rightly so in many ways, sport and exercise were part of daily life for male Greeks, as well as young female Spartans. In fact, sport and exercise were part of what made the Greeks different from their neighbours, and they recognised and celebrated this fact. The Olympic Games, traditionally said to have begun in 776 BCE and always held at Olympia, were only open to adult Greek-speaking males.

At first, the Olympics lasted a single day and comprised a single event, a foot race akin to today’s 200-metres sprint. Over time Olympic events grew, matching those commonly pursued in the Greek cities, although some – chariot racing, above all – were only for the very rich, or those funded by the very rich. They resembled military exercises, sometimes obsolete ones as with the chariots. The games were eventually held over a full five days. Team events were rare, because for the Greeks the essence of sport was individual contest and personal victory. Events included foot, horse and chariot races; discus and javelin throw; the long jump; wrestling; boxing; a pentathlon; and pankration, a combination of wrestling and boxing. Athletes trained in a quite modern way, except that they were often naked, as they would be in many of the contests themselves. As with the modern Olympics, the prize for victory was a token, an olive wreath, but only the winner was recognised – there was no reward for coming second.

Many of our sporting words, including ‘athletics’, ‘athlete’, ‘gymnastics’, ‘gymnasium’, ‘stadium’, ‘hippodrome’ and – of course – ‘Olympics’ come from Greek, suggesting just how much modern sport owes to them.

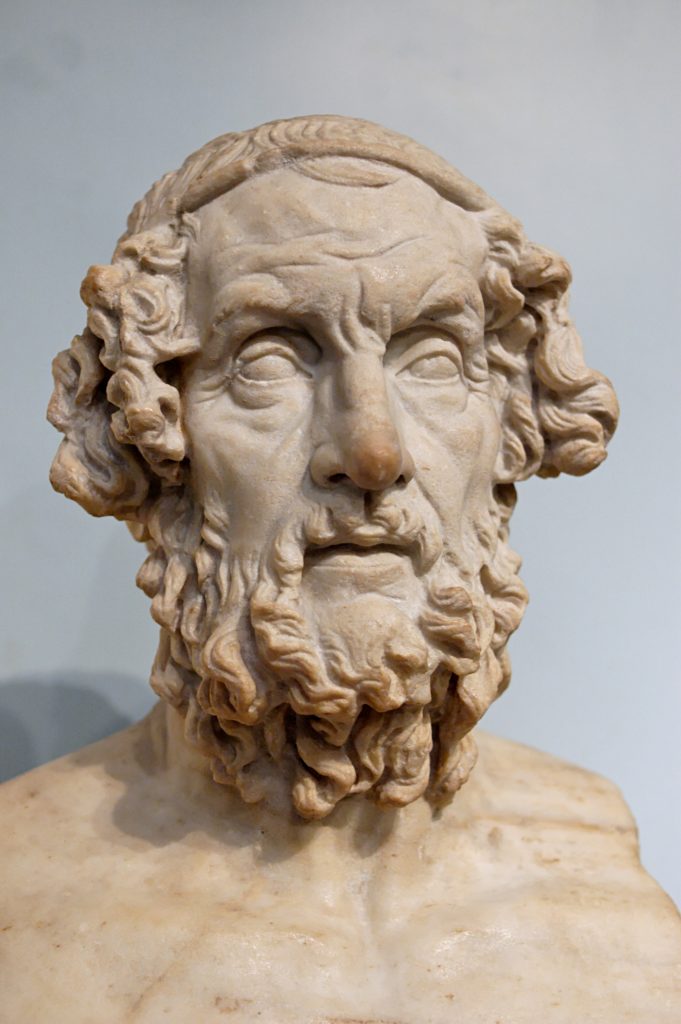

4. Literature

The Greeks established many of the genres of Western literature

The first written western literature was the Iliad, a Greek heroic poem probably written in the 8th century BCE. Lyric and elegiac poetry — originally set to music from the lyre and the flute, respectively — were Greek creations. The Athenians alone established two dramatic genres, tragedy and comedy (in two different styles), while the philosopher Aristotle codified dramatic principles in his influential Poetics. The Greeks also wrote novels, ornamental speeches and were the first people to write history; Herodotus was the first historian of any sort, while Thucydides was the first modern-seeming historian.

Only a small portion of Greek literature has survived, but what has – such as the epic poems of Homer, the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, the comedies of Aristophanes and Menander – is still read today, both in Greek and in translation.

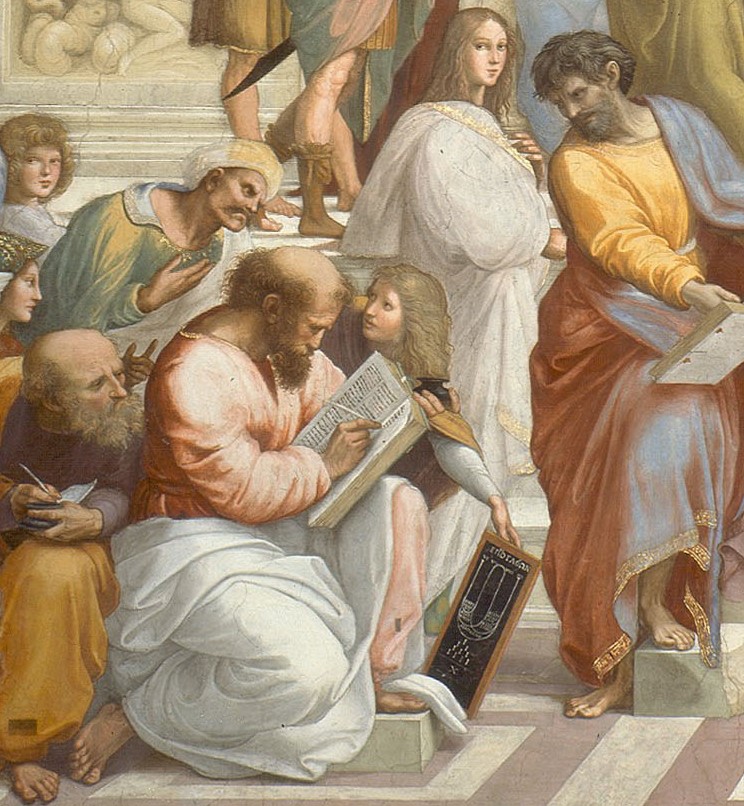

3. Education

The Athenians anticipated the widespread literacy and universities of modern democracies, while Spartans inspired totalitarian regimes with their fiercely regimented state schooling

As with so many other things, Athens and Sparta educated their children in very different ways. Other Greeks had various approaches, but most were closer to the Athenians, and by the late-4th century BCE the Athenian way was widespread. One belief they all shared was that education’s purpose was to produce good citizens.

In Sparta, a good citizen meant being a good soldier. Boys were taken from their families at seven, lived in communal barracks and were subjected to ferocious discipline and military training. Perhaps uniquely among Ancient Greeks, girls were also educated, again with an emphasis on physical and mental toughness.

In Athens, physical training was also important, but there was much more emphasis on literacy and culture. It is thought that a higher proportion of adult male citizens could read and write in 5th and 4th-century BCE Athens than in any modern European state until the 20th century. This reflected the requirements and ambitions of an active democracy.

Most Athenian boys probably only had a few years of formal education, but the well-to-do wanted more to help them compete and excel in public life. In the 5th and 4th centuries BCE higher education developed, incorporating elements of new thinking – philosophy, mathematics and the like – although the early focus was on teaching ‘cleverness’, especially rhetorical tricks.

In time, schools such as those founded by the philosophers Plato and Aristotle offered a more purely educational approach, providing the blueprint for modern universities. Academia and academics are named after Plato’s school, the Academy.

2. Maths

The Greeks didn’t invent maths, but they did have a lot of Eureka! moments

Mathematics is a Greek word for ‘that which is learned.’ Pythagoras, a semi-legendary and eccentric figure from the island of Samos – he was a vegetarian who forbade his followers from eating beans – is said to have invented the word, and much else besides. How much of this is true we can’t know, but it’s hard to dispute that many of the terms, concepts and classical problems current in maths today come from the Greeks, especially in the field of geometry. Euclid is often called the ‘father of geometry’, while Thales and Pythagoras’ theorems are fundamental. Although pi had already been calculated approximately in the Near and Far East, the first recorded mathematician to calculate it rigorously was the Greek Archimedes, in around 250 BCE. Even where Greek mathematicians were unable to answer questions themselves, they were often asking ones that would prove fruitful for mathematicians for millennia to come.

1. Philosophy

Greek philosophers didn’t only invent their own subject; they also invented science

The word philosophy comes from the Greek for ‘love of wisdom’, and is said to have first been used by Pythagoras. The Greeks didn’t differentiate between what we would think of as science and philosophy, and many philosophers were chiefly concerned with physics, speculating on the nature of the universe. Famously, Democritus (ca 460-370 BCE) expounded an early version of atomic theory. Plato is said to have despised Democritus to such an extent that he wanted to burn all his writings!

It wasn’t until Socrates (ca 470-399 BCE) that subjects with humankind as their focus, such as ethics, became fully recognised philosophical concerns. Socrates also developed the dialectical method – roughly, question and answer with an emphasis on discovering true or false statements and definitions – which has been hugely influential in many fields. What we think of as ‘critical thinking’ owes much to Socrates, who made many enemies by challenging lazy beliefs and conventional wisdom, often with mischievous humour.

Plato was a pupil of Socrates, while Aristotle was a pupil of Plato’s. Plato’s interests were widespread, but his greatest concern – the subject for his masterpiece, The Republic – was justice. His belief in the interconnectedness of things led him to state that justice could only be seen in a just state, for him a sort of philosopher’s version of Sparta, which influenced later totalitarian political thinking. Aristotle was more of a pragmatist and observer, a forerunner of social scientists in some ways, as well as physical scientists.

Other major movements included Epicurianism, Stoicism and Cynicism, all of which have spawned English words based on simplified (and somewhat misleading) versions of their teachings.

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!