King, emperor, hero, god – the name King Arthur conjures an array of images, but just how much truth is there to this ancient legend?

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

The armoured bodies lay so thick on the ground that as the rain pelted the field, it fell with an incessant ding-ding-ding upon metal. There remained but two figures facing each other across the plain; one raised his head toward the other, his visor masking his face and his black spiked armour glinting as the rain ran down the polished surface. The other stood against the setting sun, his helmet lost and his long golden hair wet against his forehead. There were wrinkles around his eyes, flecks of grey in his beard and dinks in his gleaming silver armour, but he grasped his long sword with a strong, firm grip. His foe was the first to move, stabbing his sword forward with a jerky, sudden jab. The silver knight deflected him easily with a swift, fluid movement and thrust his sword forward, driving it through his enemy’s chest. The gleaming sword sliced through the armour like silk. But his foe had landed a blow too, blood seeping from his mouth, and with his final ounce of strength he drove his sword through the silver knight’s back. There was a moment of silence as the wind moved around them, then the two fell as one.

The tale depicts the legendary Battle of Camlann, a conflict that saw the demise of one of the most famous kings in British history, a monarch so ingrained in the national conscience that his tale appears on the halls of the British Parliament. A figure with such prominence that some are so desperate to prove he was real that great excavations and archaeological digs are held in his name – King Arthur.

But who was Arthur really? Did this ‘King of the Britons’ ever even exist? Or is he simply a myth created to inspire a population in need of heroes? Although historians have failed to agree on who exactly may have inspired the King Arthur we know today, there are many viable candidates. Lucius Artorius Castus, a Roman soldier of the late-2nd or early-3rd century is a possible Arthur. This career warrior supposedly led troops of Sarmatians against invading Caledonians in ancient Britain, all the while grasping a standard bearing a large red dragon pendant – the inspiration for Arthur’s surname ‘Pendragon.’ Historians hypothesise his military victories prompted him to be raised to a figure of great bravery among the Welsh, and thus the character of Arthur was born. The problem with Artorius, just like Arthur, is that there is a staggering lack of historical recording of his supposed impressive deeds, which people would expect from a figure so prominent he became a near-immortal legend.

A man actually called ‘King of the Britons’ in ancient sources is Riothamus who lived in the 5th century. Riothamus reportedly travelled into Gaul twice, just as Arthur did, and was betrayed by a close friend, just as Arthur was. And when Riothamus died he was near a town called Avallon, while Arthur was supposedly carried off to ‘Avalon’ upon his death. Comparisons have also been drawn between Arthur and Ambrosius Aurelianus, a Romano-British leader who was well known for his victorious campaigns against the Saxons. There are also theories that Aurelianus commanded the forces at the Battle of Bandon Hill, the very same battle where Arthur apparently led an army. Aurelianus is recorded as having the virtues of a ‘gentleman’ and was a Christian – two key qualities Arthur shares.

One of the more unusual origin theories of Arthur’s origin comes from his name itself. Deriving from the Celtic word ‘Art’, meaning ‘bear’, it is possible that Arthur is simply a personification of a Celtic bear god. The Celtic tradition of worshipping revered animal spirits was popular, so it would make sense for their celebrated hero to originate from such beliefs.

There are plenty more candidates for possible Arthurs, as any warrior who was successful in ancient Briton with a vaguely similar name seems to be a feasible option, whether any of these are actually the true Arthur of legend we may never know, but one thing we can trace reasonably accurately is Arthur’s emergence and journey through literature.

The very earliest mention of Arthur is in Historia Brittonum written in 830 by Nennius, a Welsh monk, which says: “Then in those days Arthur fought against them with the kings of the Britons, but he was commander in those battles.” Because of the vague mention it is difficult to assess whether this Arthur was actually a king himself or simply a mighty warrior. Nevertheless he goes on to list 12 battles Arthur was involved in, 12 battles that occur over such great distances and lengths of time that it would be impossible for one man to fight in them all. This somewhat fictional ‘historical’ list sows the very first seeds of doubt of Arthur’s legitimacy – or perhaps instead, the origins of a myth.

The next time Arthur crops up is in the work of Geoffrey of Monmouth, another Welsh cleric. In his mammoth chronicle Historia Regum Britanniae, Arthur takes on new life and some of the best-known parts of his tale come into being. Apparently based on a lost Celtic manuscript that – conveniently enough – only Geoffrey was able to read, the apparent historical book details the story of King Arthur’s life from his birth to his betrayal and death. This is also the first instance we are introduced to some of the most famous people in his story, such as Guinevere and Merlin. The book was an instant success and 200 manuscripts are still around today – a tremendous number for a Medieval work, which demonstrates just how successful it was. But why did the Britons take on this tale of an ancient king so enthusiastically? What was it about Arthur that made him so popular?

The answer is pretty simple, and rather cliché – Britain needed a hero. After the Norman invasion of 1066 the kingdom was in turmoil, and it wasn’t just Arthur’s tale that emerged – a host of Celtic literature depicting glorious victories against the invading armies infested the folklore. These tales became interlinked with history, demonstrating the illustrious and noble past of the Celts. Geoffrey’s tale of a strong Celtic king who defeated the barbarians and waged war against the Romans, which was subtly and cleverly linked to real-world events, like the battle of Mount Badon (which Arthur is not mentioned in relation to until Historia Brittonum) was the perfect intermingling of fact and fiction for a nation that needed a strong figure to help them keep a hold on their identity.

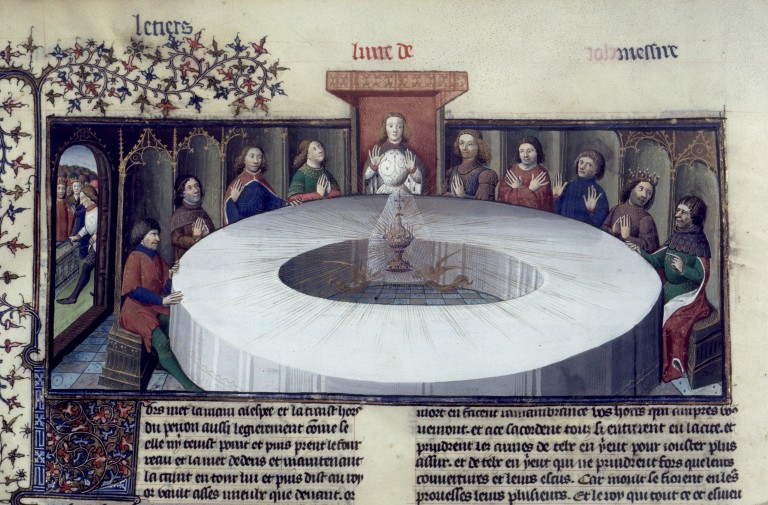

However, it was Arthur’s emergence into French culture that gave the tale some of its most notable aspects. When Henry II married Eleanor of Aquitaine, the very English world of Arthur was introduced into the romantic and sublime world of French literature. One of the most famous French writers of the period, Chrétien de Troyes, was enraptured by the idea of the noble warrior king and penned new tales of Arthur and his court, transforming him from a mighty warrior into a leader of a spiritual quest, turning his world from one of blood and steel to courtly romance and the search for the mysterious Holy Grail. The iconic Holy Grail first appeared in Chrétien’s poem Perceval, The Story Of The Grail, which he claimed was written from a source given to him by Philip, Count of Flanders.

It is unclear whether people in the Medieval era considered Arthur fact, fiction or a mixture of both, but just 100 years after Monmouth’s book was published one person was very keen to demonstrate it was as close to fact as it could be – King Edward. It would have been advantageous for the king who led a crusade of the Holy Land to prove his connection to the mightiest and most revered king in British history – Arthur. With his spin doctors demonstrating proof that Edward was a descendant of Arthur himself, it added weight to his right to unite all the people, and he successfully subjected a rebellious Wales to English law. In a world where the king’s word was law, Arthur’s legitimacy wasn’t even brought into question.

Edward wasn’t the last king to use the strength of Arthur’s legend to cement his own hold on the throne. The Tudor monarchs claimed their lineage could be traced directly to the legendary king and used the power of the legend to prove the legitimacy of their claims to the English and Welsh thrones, vital for a dynasty that originated from an illegitimate child of English royalty.

Henry VIII was a very vocal supporter of King Arthur and the concept of honour, and even commissioned the Winchester Round Table, most likely created in the reign of Edward I, to be repainted with himself in the position of Arthur. Again in the midst of national change during the Industrial Revolution, Britain’s monarch called upon the power of the legend of King Arthur, with Queen Victoria using the image of Arthur’s chivalrous knights of the realm in connection with Britain’s imperialist nature as the empire expanded. Bolstered by the people’s faith that Britain was creating a worldwide Camelot, the British Empire grew to become the largest of all time.

It would be easy to assume from this that King Arthur was nothing more than a political ploy, an inspirational tale used by opportunists to further the power of British monarchs over the people, but Arthur’s influence stretches further than that. More than a political myth, the story of Arthur’s righteous and heroic court began to embody Britain itself. During the Middle Ages it was the Arthurian tales of just and noble conduct, of brave knights rescuing maidens in distress, that inspired the knights’ code of chivalry. This idea of a knight’s duty to his countrymen and fellow Christians helped to launch ships, win battles and change the political landscape of the world as we know it. This in turn encouraged the creation of a code of etiquette and morals that Britain is, for many, still defined by today.

So did the King Arthur we know of from the tales actually exist – drawing swords out of stones and taking advice from an elderly wizard? Almost certainly not. Although it’s highly likely he was based on brave warriors of the era, all the evidence points to King Arthur being borne from the imagination of the men who recorded his tales. But does this mean he isn’t real? Not really. Whether he existed or not, King Arthur and his tales of chivalrous victory have had a remarkably deep effect on British culture, more so perhaps than any living person. The stories of Arthur’s life and his thrilling adventures have transcended time, developing into new and innovative forms along with the country itself. From its early origins of a noble warrior beating impossible foes, to a shining light of goodness and justice guiding the soldiers in the trenches of World War I. Perhaps the most remarkable story here isn’t of an actual king who rescued maidens and accepted swords from mysterious lake dwellers, but instead the true tale of how someone who didn’t actually exist has embedded himself so profoundly in the entire history and culture of a nation that even today, over a thousand years after his creation, we entertain the possibility of him being real.

Originally published in All About History 21

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!