Discover the the daughters of Freyja, their relationship with religion and their devotion to one Norse goddess in particular

From the one-eyed god Odin to his hammer-wielding son, the thunder god Thor, Norse mythology is full of colourful deities. They were an integral part of the Old Norse religion, paganism, which was displaced in Scandinavia by the end of the 12th century with the arrival of Christianity. However, out of all of them, there was one pagan deity whose popularity continued to rise after Christianisation: Freyja. Devotion to her remained strong among Norse women despite Christian attempts to stamp out her popularity.

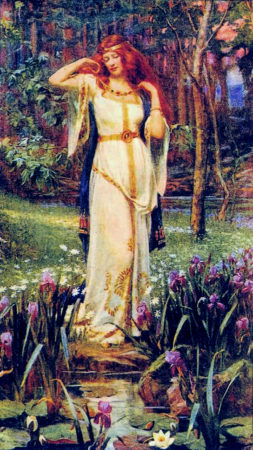

Freyja, along with her brother Freyr, was the child of Njörd and his sister, whose name remains unknown. She was married to Oðr and together they had two daughters, Hnoss and Gersemi, although Oðr’s eventual disappearance leaves Freyja heartbroken. She is the goddess of love, sexuality, fertility, magic, war and death, portrayed in Norse mythology as a strong and independent deity, especially after the disappearance of her husband. The majority of the information regarding Freyja comes from the 13th-century Icelandic sagas, most prominently in the Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson, who refers to her as “the most renowned of the goddesses.”

If there is one thing that can be assured, it is that Freyja was definitely a goddess who was not to be messed with. For example, when the giant Thrym stole Thor’s hammer, Mjölnir, he agreed to return it on the condition that Freyja was given to him as his wife.

While Thor and the other gods were ready to cede to these demands, Freyja was left outraged and refused to cooperate. As a result, Thor was forced to dress up as a woman, pretending to be Freyja, to trick Thrym in order to regain his hammer. To the giants, Freyja was an object of lust and desire and was subject to their various plots and schemes to trap her into a marriage, as mentioned in the sagas.

Freyja’s ability to refuse these marriages reflects the real-life situation of Norse women. Despite the image of brutish and forceful men that may be conjured up when thinking of the Vikings, Norse women generally couldn’t be forced into a marriage against their will. Marriage was seen as an arrangement between families to build social alliances with each other, rather than as an institution of love. A male relative, usually her father or her brother, represented the bride

during the marriage negotiations.

A happy marriage was in everyone’s best interests as it was a financial investment. The bride’s family were compensated for the loss of her labour, known as the bride-price, and the groom took her dowry. It was good practice to seek a bride’s approval of her future husband — an unhappy match could lead to divorce, ending the alliance that had been built.

Surprisingly, divorce was a relatively easy affair for the Vikings, for both men and women. Wives had the same rights as their husbands to end their marriage and they were often the ones to initiate a divorce. A woman could request a divorce if she caught her husband wearing feminine clothing and, in turn, he could divorce her if she wore masculine clothing. In some cases, a marriage could be ended if a wife and her husband had not slept together for three years or, quite simply, because the couple were unhappy.

The most popular reason that was cited in the sagas for divorce was violence — if a man slapped his wife three times in front of witnesses, she could go for a divorce. Compared to modern court proceedings, Norse couples simply had to state their reasons in front of witnesses before it was officially confirmed. The division of property was also an easy process as each party essentially left the marriage with what was originally theirs.

Although Norse women had a substantial level of independence when it came to marriage, they were still in an inferior position compared to the men in their society. It is easy, with sagas depicting tales of Freyja, shield maidens and strong, fierce women, to fall into the wishful trap that women held in a far more superior position than would be expected of the time.

Regardless of her greater freedom in terms of marriage, a Norse woman’s role was primarily to manage the household and the farm, particularly if her husband was away. Even in circumstances where a woman held some form of political power, perhaps because of her wealth, she was still responsible for the running of the home. That being said, it was also women who held absolute authority when it came to the household and so they still exercised influence in this way.

The situation was slightly different for widows, especially those of a high status. These women had the right to marry whoever they wished and could distribute their wealth however they saw fit. It was not uncommon for aristocratic widows to be able to support themselves as women held the right to inherit property and land. A woman who was mistress of her own property, or owned her own estate, was known as ‘the lady of the house’ in reference to Freyja, whose name literally meant ‘the lady’, in honour of her popularity.

Along with running the household, a woman was also expected to provide her husband with children. For this reason, sacrifices to Freyja formed part of the wedding ceremony in the hope that the goddess would bless the newlywed couple with fertility. The sacrifice was usually a sow, the animal associated with Freyja.

She would also be called upon during childbirth, which was a dangerous and uncertain experience for Norse women. It was hoped that she would protect the mother and child, ensuring that the birth would go smoothly. As Freyja was known for her unbridled sexuality, it is unsurprising that she was worshipped for her role in fertility. At one point, it brought her into conflict with Thor’s brother, Loki, after he accused her of wanton and incestuous behaviour in Lokasenna, one of the poems from the Poetic Edda.

Such faith was held in Freyja that women are believed to have taken part in numerous fertility rituals dedicated to her, which managed to survive even after the adoption of Christianity. It is really difficult to get to grips with the process of pagan worship, thanks to the lack of contemporary sources that are available today. Indeed there are the sagas where a large proportion of the information regarding Norse mythology derives from, but they were composed in the 13th century, some 200 years after the conversion to Christianity, and for the most part are inaccurate.

This also creates another problem, as the men who wrote the sagas typically failed to pay much attention to the subject of female worship — so how do we know that Norse women continued to worship Freyja after the decline in paganism? Well, there are a number of places, particularly in Sweden, which we know have names derived from or that are associated with Freyja. To choose names in honour of her is a testament to the goddess’ continuing importance in Norse society and to Norse women as a deity of fertility.

Worship of Freyja was certainly at odds with Christianity. Not only was she a lingering reminder of paganism, but also her sexually vivacious reputation went against the Christian ideal of a chaste woman. Young lovers would call upon her to support their affairs while women continued to look to her for matters on love and fertility.

Freyja was said to enjoy love poetry and, as a result, it soon became illegal under the new religion as Christians began to target the free-willed goddess and her popularity. For this reason, it is surprising to learn that the majority of Norse women actually embraced Christianity, despite its use of patriarchal oppression.

For Norse women, Christianity actually offered them some really appealing options that paganism could not. Most notably, it denounced infanticide — a practice that was used frequently among the Vikings, especially towards female infants.

It has been suggested that this is the reason for the lack of female remains discovered in Scandinavia that date back to the Viking Age, with the exception of Birka, Sweden, where the number of female graves outnumbers the men’s. For any Norse mother, the thought of a religion protecting her children from harm would have surely encouraged her conversion.

Another reason that women accepted Christianity so easily was its promise to give them a better afterlife. Valhalla, the hall of Odin, was not accessible to women after death as it was the destination for those who had died in battle.

There is no explicit evidence that clarifies where Norse women were expected to go once they had died. However, going by the graves of Norse women, who were usually buried with jewellery and household tools, it can be assumed that they did expect to enter the afterlife. It left them with one option: the realm of Hel.

Hel was a dark, dreary and depressing place, not exactly the dream place for women to spend their afterlife. It is hardly any wonder that women turned to Christianity in the hope that one day they would reach something better.

Speaking of the afterlife, it is interesting to note that although she was a deity of stereotypically feminine attributes, Freyja also played a key role as the goddess of war and death. As told in the Eddic poems, she got to choose half of the warriors who were slain in battle to enter her hall, Sessrúmnir, on the field of Fólkvangr, while Odin received the rest.

Judging by Egil’s Saga, it has also been assumed that perhaps women believed they could also go to Freyja in the afterlife. Egil’s daughter, Thorgerd, threatened to starve herself to death when her father refused to eat after the death of his son. She declared, “I have had no evening meal, nor will I do so until I join Freyja.” Does this imply that women could hope for an afterlife with the goddess? Unfortunately there is little information out there, besides Egil’s Saga, to suggest that Norse women could go to Freyja after death.

Considering existing evidence, it is generally assumed that while those killed in battle went to the halls of Freyja and Odin, everyone else went to Hel. This leads to the conundrum of female warriors, also known as shield maidens.

Whether women actually held roles in the military continues to provoke heated debates, particularly when it comes down to recent archaeological findings, with arguments for and against. If women did indeed fight as warriors, it is certainly worth thinking about whether they would have been allowed to enter Freyja’s hall, or even Odin’s, on the basis of their profession rather than their sex.

Despite the advantages for women adopting Christianity, their devotion to Freyja continued, if the sagas are to be believed. It was said that out of all of the Norse gods, Freyja became the last living deity after the death of her brother. She continued to perform sacrificial ceremonies, increasing her popularity with her worshippers.

As Christianity tightened its grip across Scandinavia, Freyja gradually became assimilated into Scandinavian folklore. Although the role of Norse women in society and religion changed as paganism began to fade, it seems that there was still some focus on the traditional mythology and worship of the fertility goddess.

Read about more the Vikings and their greatest explorers in All About History 76, available now