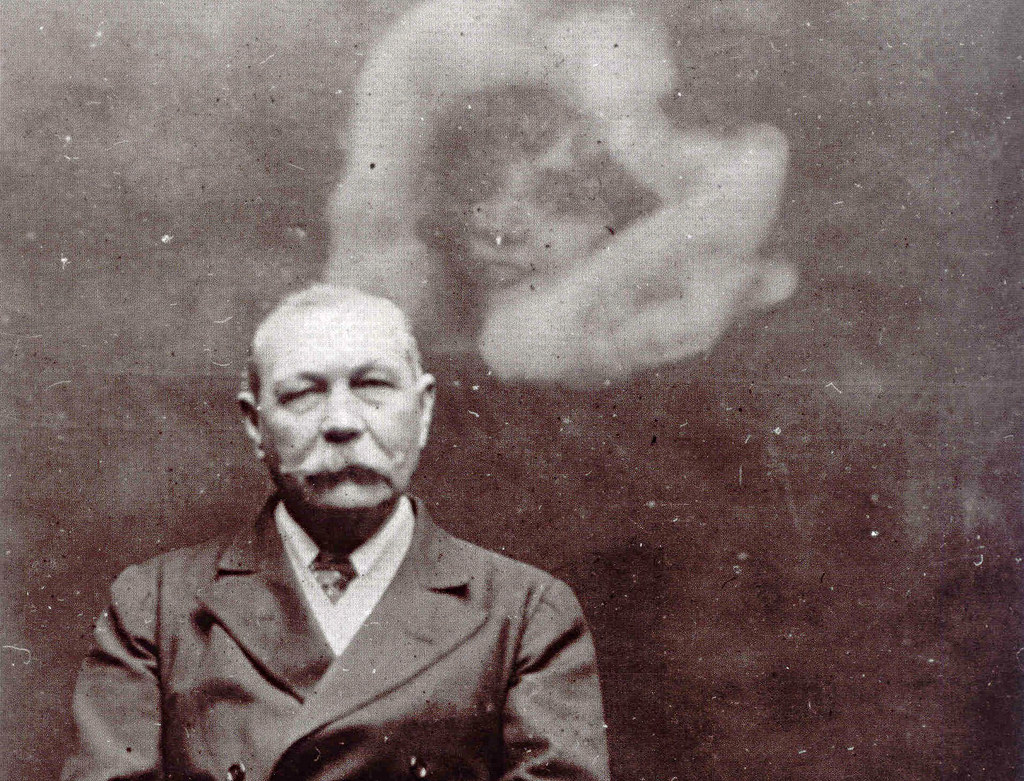

The esoteric worldview of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle is a constant source of fascination. From his embarrassing evangelism on behalf of the Cottingley Fairies hoax to his opining on the alleged Curse of Tutankhamen, it’s hard to reconcile his outlandish personal views with his role as the creator of literature’s arch-rationalist, Sherlock Holmes.

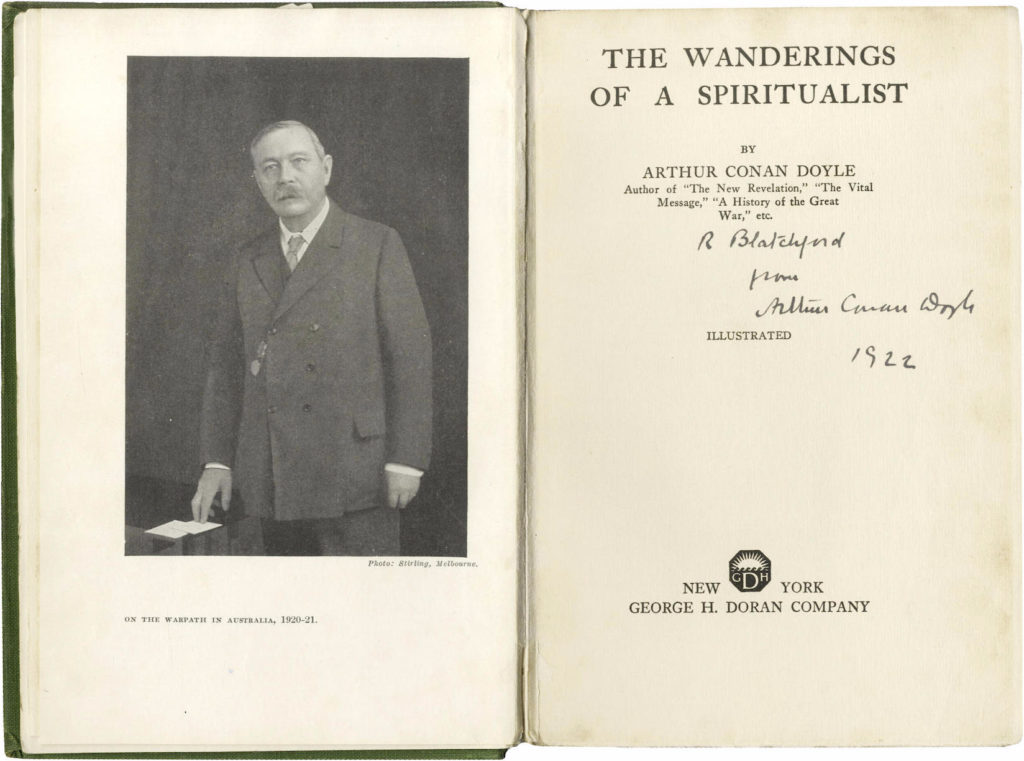

Christopher Sandford know this struggle better than most. A major part of his 2011 book Houdini and Conan Doyle: Friends of Genius, Deadly Rivals which explains how the writer and the illusionist came to verbal blows over their polar opposite views on spiritualists, Conan Doyle’s views on the occult and the supernatural are also reflected in Sandford’s latest book, The Man Who Would Be Sherlock: The Real Life Adventures of Arthur Conan Doyle which places Sherlock’s fictional cases into the context of his creator’s own gruesome experiences.

We spoke to Sandford to get an idea of how literature’s master of logic can be squared with the beliefs of his creator…

There’s a real gap between Doyle identifying as a spiritualist in the 1880s and the sort of evangelism that alienated him from many of his peers following World War I. What changed for him? And how would you characterise his changing positions?

I think you’re quite right in saying that ACD’s views on the occult evolved over time rather than being a case of overnight conversion. He was certainly experimenting in areas like mesmerism and telepathy while still a struggling young doctor in Southsea in the early 1880s, when he was only in his mid-twenties.

I don’t claim to have any great powers of psychological insight into Doyle’s mind, but I think it pretty fair to say that his was a case of a supremely rational (if you like, Holmesian) scientific intelligence tempered by a growing dissatisfaction – or eventually full-scale divorce – from the sort of extreme Roman Catholic orthodoxy he grew up with. Mix that in with a vein of classic British eccentricity (Doyle’s father, you’ll remember, ended his own life of the starkly named Montrose Lunatic Asylum) and a lifelong tendency to see the best in people – even should they be obvious charlatans or hucksters – and you’ve got the essential ingredients for what was about a 35-year spiritual progression.

The final tipping-point was of course WW1. I think ACD lost no fewer than eleven family members either in combat or to disease, his eldest son and only brother among them, and you can see how as a result some of the above factors might have met with a fierce if not overwrought need to prove his dictum, ‘There is no death.’ Meanwhile, I think it fair to say that Doyle’s central message of life going on met with a broadly sympathetic response among the many people around the world who’d suffered their own wartime losses; but perhaps less so as time went on and his natural tendency to lecture or evangelise grew more pronounced.

By the time the Christmas 1920 edition of The Strand appeared with the front-page banner headline ‘Fairies Photographed: An Epoch-Making Event Described by A. Conan Doyle’ you had roughly half the world – including the likes of Harry Houdini – convinced he was off his rocker.

Can his spiritualism be reconciled with the arch rationalism of his most famous creation?

Similarly, the road from ACD’s fundamental rationalism to his being (quite literally) away with the fairies was a long and winding one. I’m frankly not sure he ever fully abandoned some of his more, if you will, dourly Scottish, or pragmatic, slant on life. There’s the line in The Sussex Vampire – written well after Doyle had come out as an occultist – in which Holmes announces: “This Agency stands flat-footed upon the ground, and there it must remain. The world is big enough for us. No ghosts need apply.” Or for that matter among the very last lines Holmes ever utters, in The Retired Colourman: “Is not all life pathetic and futile? Is not his story a microcosm of the whole? We reach. We grasp. And what is left in our hands at the end? A shadow. Or worse than a shadow – misery.” There surely speaks a man who may well have been alive to Spiritualism’s core promise (‘God does not throw us upon the scrap-heap’ is one of CD’s repeated quotes of around the same time) but who was still quite hard-headed and realistic enough to see life for what it was.

Doyle’s enthusiastic adoption of the Cottingley Fairies hoax is perhaps the most infamous episode in his lurch toward the supernatural, but fairies seem to sit outside of the pseudo-science of spiritualism, how did Doyle rationalise them?

The Cottingley Fairies saga – which incidentally got underway in July 1917, exactly 100 years ago – is indeed a bit of an anomaly. ACD always said that the alleged sprites represented a ‘primitive’ life form, and thus didn’t strike him as quite as evidentiary of an afterlife as the traditional spirit summoned by a medium.

You could just about argue that by the stage he went public on Cottingley in the early 1920s he was only too happy to seize on any chance he got to discredit Catholic orthodoxy. So a significant part of it was almost certainly intellectual opportunism on his part – if the Pope had somehow come out all in favour of the fairy story (as opposed to the simultaneous children’s visions of the Virgin Mary in Fatima, Portugal) it’s fair to ask if Doyle would have been quite as keen to lend his name to the whole tale.

It’s probably also worth remembering that ACD’s father Charles had a habit of producing vivid sketches of fairies and ‘miniature people’ in general, and that Arthur quite openly – and presumably proudly – displayed these in his various homes (Tennyson Rd, South Norwood, for sure) long before he came out as a Spiritualist.

Doyle frequently pops up on lists of members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Is this a flight of fancy or is there any truth to this?

As far as the Golden Dawn goes, all I’ve ever heard is that Doyle either a) nominally joined but failed to take an active part in proceedings; or b) politely declined to sign up. (He did of course have some track record as a Freemason.)

There’s an interesting symmetry between the Houdini/Doyle relationship and the later Houdini/Lovecraft one, with the former pushed apart by their conflicting views on spiritualism and the latter drawn together because of it. Did Doyle have any opinions on Lovecraft that we know of?

Interesting point you raise about the ACD/Houdini/Lovecraft axis. All I know for sure is that Lovecraft himself at one time acted as Houdini’s ghostwriter (poignant term), and I think I’m right in saying helped him compose – if not actually composed – a c. 1924 tale glorying in the title ‘Imprisoned with the Pharaohs’, which itself owed something thematically to Doyle’s The Sign of Four.

Houdini noted serenely in his diary that he was personally gratified by the opportunity to “meet the intelligentsa” [sic] that his new literary activities brought him. Alas, Lovecraft himself was less impressed by the whole exercise, going on to curtly dismiss his patron as a “bimbo” who was “supremely egotistical, as one can see at a glance.”

All I can add is that just as Doyle seemed to accelerate psychically speaking around his mid-60s, so he applied the brakes culturally. By then his tastes in literature ran to the likes of Winston Churchill, Thomas Hardy and Rudyard Kipling, and we know that he was singularly unimpressed by Radclyffe Hall’s lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness when it appeared in 1928. “We do not want to see this country in the same condition as France, which has a great quantity of pornographic [books] in circulation,” Doyle harrumphed. Notwithstanding his occasional taste for science fiction and the macabre end of the spectrum, I’d say all the evidence suggests he wouldn’t have been among Lovecraft’s natural admirers!

The Man Who Would Be Sherlock: The Real Life Adventures of Arthur Conan Doyle is available now from The History Press. For more on the world of Victorian crime pick up our Book of Sherlock Holmes or Book of Jack the Ripper.