For centuries, duelling was a gentleman’s right to keep their honour, before the practice was made unlawful. However, there was still time for one last duel in England…

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

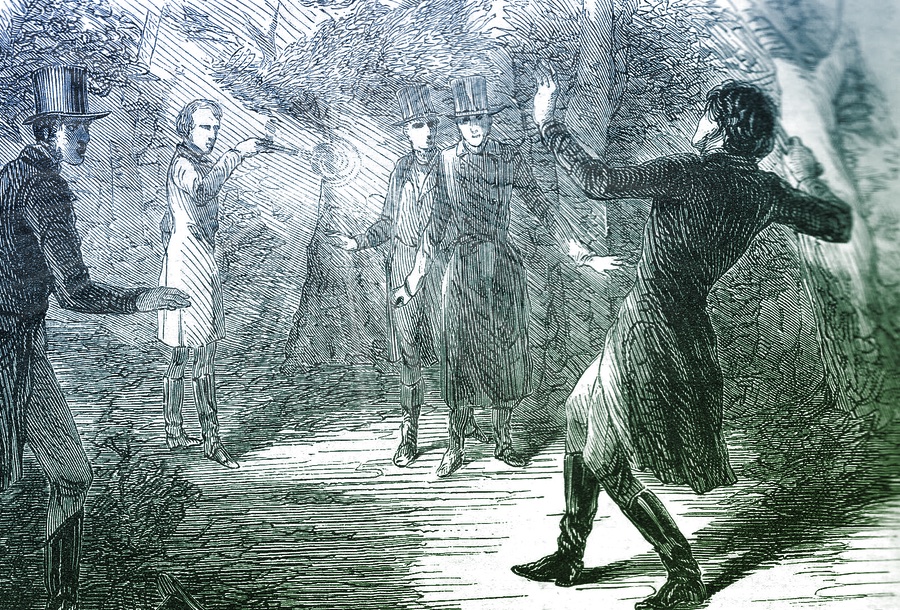

Late in the afternoon on 20 May 1845, four young men slip out of Gosport near Portsmouth and make their way to a remote beach. Minutes later, pistol shots echo across the afternoon sky and two men are seen fleeing the scene, as another crouches over a prostrate body that is crying out in agony. The four men have just taken part in the last fatal duel between Englishmen on English soil.

Duelling had been the way officers and gentlemen settled matters of honour for centuries. Up until the mid-19th century there were certain situations where a meeting with pistols or swords was seen not just a possible response to a perceived insult, but the only honourable one. Men risked being ostracised from society for not issuing a duelling challenge in response to an insult.

One of the reasons for the decline of duelling was that the definition of what constituted an insult requiring ‘satisfaction’ became so broad that men were dying over trifles and a hasty word or two, where the pettiest of quarrels could lead to pistols at dawn. For instance, in 1805 two officers, one army and the other navy, were riding their horses in Hyde Park while exercising their dogs. The dogs got into a fight, the owners argued about whose dog was at fault, and the result was a duel that same evening at the almost suicidal distance of six yards. One was wounded, the other killed. A duel over such an incident was not uncommon.

By the time of the ‘last duel’, duellists were likely to be condemned, ridiculed or both. The attitudes of society and those in positions of power had changed. It became so hard to arrange a meeting without it being discovered and intercepted by the authorities that adversaries were having to go to ever-greater lengths of secrecy and subterfuge. Queen Victoria made her displeasure of the practice known; Prince Albert called it ‘barbarous’ and was a prime mover in putting an end to it. Wellington, the iconic military figure of the day, worked with Prince Albert in changing attitudes. Ironically, Wellington himself took part in a duel that was one of the nails in the practice’s proverbial coffin.

Throughout history, some form of combat has often settled disputes between men, making it difficult to pinpoint when duelling began. The concept evolved to a certain extent from trial by Ordeal, which had become an accepted avenue for settling grievances in early medieval Europe, but it was during Elizabethan times that the ‘true’ duel, the duel of honour, became an established phenomenon in Britain. Written guides imported from Italy began to influence English thinking on such things as etiquette, chivalry and honour – as did the idea that breaches of such codes should be settled by duelling.

When duelling became unfashionable in the mid-19th century, there wasn’t any need for a specific new law because existing legislation to do with violence, manslaughter and murder already covered all aspects of the practice. The one important move at this time was a change to the Articles of War, which governed the behaviour of army officers. Prince Albert had wanted to introduce a ‘court of honour’ to which officers could take their grievances instead of duelling. Although this was rejected, the sending and accepting of challenges was banned in 1844 under the revised Articles of War, and the Royal Navy adopted the same principle. In this respect, Britain was ahead of the times. Duelling in Europe continued for much longer – for several decades in France.

The last fatal duel in England had its roots in 1845 when Lieutenant Henry Hawkey of the Royal Marines and his attractive wife Isabella met James Alexander Seton, a former cavalry officer in the genteel Portsmouth suburb of Southsea. They were all in their mid-twenties. Before long, the wealthy Seton was paying Isabella a great deal of attention. He offered her gifts, suggested trips in his carriage and visited her at home when he knew Hawkey was on duty. Isabella Hawkey later portrayed herself as a completely innocent victim of his predatory ways but this account has been questioned. Seton was an arrogant, determined man and barely made a secret of his lecherous designs. Hawkey certainly had his suspicions and instructed the landlady to make excuses to interrupt Seton and his wife if the former ever called on her while he was out.

Things came to a head during a ball, when Seton insisted on dancing with Isabella against Hawkey’s wishes. Seton made overt advances while they danced, having already said he had no fear of ‘going out’ (ie duelling) with her husband if it meant he had his way with her. Hawkey knew something was amiss and, finally provoked beyond the limits of his patience, took Seton to one side. No one knows exactly what words were spoken, but Hawkey almost certainly demanded a meeting, because Seton’s air of bravura was instantly dropped and he claimed it was beneath a cavalryman to duel with a mere ‘infantryman.’ This was not only insulting to both Hawkey and the Royal Marines but a cowardly way of avoiding a duel. It didn’t work. Hawkey knew that if he made a big enough scene, Seton would be humiliated into having to offer a challenge. As Seton attempted to leave the King’s Rooms, Hawkey accosted him, threatening to ‘horsewhip him up and down the high street’, and even kicked out at him. Seton had been backed into a corner. Early the next morning, a friend of his arrived at Hawkey’s house and issued Seton’s challenge.

Hawkey chose young, inexperienced fellow marine Edward Pym as his own second, probably because they were close friends, but then found himself in the awkward position of not owning duelling pistols. As a military man he would obviously have had access to firearms of all kinds, but duelling pistols were specialist weapons whose design had evolved over the years to suit their sole purpose. He and Pym were obliged to trawl the gun shops of Portsmouth until they were able to obtain a good pair.

There were rumours Hawkey had been involved in a previous duel and he was certainly not a man to be trifled with; he was a serving officer from a family with a strong military tradition and had seen military action. His own father had killed a man in a duel. Seton, by contrast, was something of a fraud. He liked to boast about his cavalry background and his time with the illustrious Eleventh Hussars, of Charge of the Light Brigade fame. But the reality was that the grossly overweight Seton’s time in the saddle was brief and unglamorous. He had purchased his cavalry commission, and although this was common at the time, he was not the captain he was often described as at the time and in subsequent retellings of the story, but a mere cornet – the lowest commissioned rank. Moreover, his ‘career’ only lasted 12 months.

At 5pm, Hawkey and Seton took up their places at a distance of 15 paces and readied themselves. In the public consciousness, dawn is the typical time for duels and it was indeed a fairly common time for duels to take place because it lessened the chances of being interrupted or witnessed. However, there were no set rules and basically any time and place that suited the participants was considered acceptable. The same applies to duelling distances; it was up to the principals and seconds to come to an agreement. A kind of convention did evolve over time, though, and most duels were fought at around 12 paces; 15 was at the upper end of the scale, but not uncommon. Eyesight occasionally played a part in the decision, and it may have done so here. Seton was afterwards to say: “Had we stood at the distance my opponent wished (six paces) he would now have been in my place and I his.” This could well indicate that he was near-sighted and hampered by the much longer distance.

One of the seconds gave the command to fire – but only one pistol shot rang out. When Pym had handed Hawkey his pistol, it had been at half-cock and so incapable of discharging its ball. An experienced second would have realised that his man was about to receive a shot without being able to return fire himself and alerted him. Luckily for Hawkey, Seton missed with his shot. Smooth-bored flintlock pistols firing round balls weren’t the most accurate of weapons, so this was hardly surprising. An ex-army officer carried out a statistical analysis of known duels in the pistol era and calculated that around half of duellists were wounded and about a fifth killed.

By the accepted principles and etiquette of duelling, the duel should now have been halted. Seton had fired and missed and Hawkey’s misfire also counted as a shot. Both men could leave with their honour intact. The seconds could and should have intervened. But now, controversially, Hawkey and Seton were handed their second pistols. According to Seton’s wife, it was Hawkey who demanded that they both shoot again – but even if this is true, Isabella drew attention to the fact that Rowles did not withdraw Seton after his man’s first shot had been “received but not returned”.

Perhaps Hawkey’s simmering hostility towards Seton was such that neither second could impose their will on him. For whatever reason, Hawkey and Seton went to their marks once more and faced each other, waiting for the word. Seton missed again, but this time Hawkey made no mistake. Because of the sideways stance adopted by duellists, the ball entered his opponent’s right hip. It passed through his lower abdomen wall and exited from his left groin. Blood from the wound sprayed the shingle for a distance of 70 to 100 centimetres, (two to three feet), signifying an arterial bleed, and Seton crumpled to the ground. Hawkey is reported to have simply uttered: “I’m off to France”, as killing someone in a duel was the same as killing them under any other circumstances – against the law – and a witness reported seeing two men dressed in black running along a lane, hiding their faces as they raced desperately past him.

Seton was transported to a hotel, where a life-threatening aneurism was diagnosed. The artery was repaired, but within days Seton began to exhibit signs of a major infection. He died about two weeks later – the last Englishman to die in a duel on English soil. Hawkey and Pym went to ground and that appeared to be the end of the matter. There was something of a national sensation a year later, therefore, when Pym resurfaced and handed himself in. A young and promising officer, he was visibly affected by the way his life and career had been turned upside down out of a sense of loyalty to his friend. He gained the sympathy of the jury and was acquitted. This was perhaps the signal Hawkey himself had been hoping for, because he now also offered himself up for trial.

His barrister’s strategy was the same that had been employed at Pym’s trial: Seton hadn’t been killed in a duel, but as the result of surgery that, according to the defence, might not even have been necessary. Just as in Pym’s trial, the judge made it quite clear that this was no defence in law. Seton’s surgery was performed in good faith and only as a direct result of his being shot, but again the jury blithely ignored him. A verdict of innocence was announced and cheers echoed around the Winchester courtroom. Hawkey left the building a free man, blissfully unaware this would not be his last courtroom appearance. Duelling was by now officially banned in all branches of the military, one of the last vestiges of society where it had still been partly accepted, but politicians had imposed this and old ways die hard. Not long after the trials, both Pym and Hawkey were quietly reinstated into the Royal Marines and in fact were promoted within two and four years, respectively. Pym went on to have a successful career, retiring as a general. Hawkey was not so fortunate.

Seven years after the duel, a Royal Marines officer riding his horse to the Woolwich barracks intervened when he saw one fellow officer attacking another while a distressed woman looked on. The woman was Isabella Hawkey, and her husband Henry was assaulting Lieutenant Henry Swain with his stick and fists. At the subsequent court martial, the whole humiliating story came out. Isabella had been having an affair with Swain that everyone seemed to know about, including Hawkey, but he had been kidding himself. When he and Isabella came upon the man at the centre of the rumours, Hawkey snapped. At the subsequent court martial, Swain’s regular calls on Isabella when Hawkey was on duty – echoes of James Seton – were revealed in lurid detail. One servant spoke of entering a room and witnessing Swain jumping up from the settee and buttoning up his trousers. Hawkey, conducting his own defence, would have been hearing these stories for the first time. The military court decided that Hawkey was: ‘…guilty of having violently assaulted First Lieutenant Swain… but that he is not guilty of conduct unbecoming the character of an officer and a gentleman.’

He was acquitted, his sword was returned to him and there were handshakes all round but within weeks of the verdict Hawkey (along with Swain) was placed on permanent half-pay. In modern parlance, he had been forced into early retirement. He tried to sue Swain, tried to buy a commission in the army – but his meagre pay and savings were stretched beyond breaking point and in 1853 he was back before the Winchester courts, this time as an imprisoned debtor as Isabella married a poet 11 years her junior. Hawkey died a few years later aged 39 of tuberculosis, alone in a lodging house. He is often portrayed as a tough, irascible marine and when he was out searching for duelling pistols with Pym on the day of the duel, a witness at his trial reported overhearing him say: “I’ll shoot him as I would a partridge.” However, the court martial for his attack on Swain revealed the surprising fact that on the sleeve of his scarlet Royal Marines uniform, Hawkey wore a black armband in memory of Seton, the man whose life he had ended in a duel for honour. In less than glamorous circumstances the other man to have taken part in the last fatal duel on British soil, the last participant in a ritual dating back hundreds of years, had died.

Even in military circles, attitudes towards duelling had changed. Officers against the practice had previously been drawn into duels for fear of being labelled cowards, but a sign of the times was when General Sir Eyre Coote, a battle-hardened soldier whom no one could accuse of cowardice, refused to accept a challenge by another officer but instead referred the matter to his commander-in-chief – who happened to be King George, the nominal head of the army. The king made it known that Coote had acted quite properly, and gave his challenger a devastating public dressing-down.

By the time of the duel between Seton and Hawkey, the general public were far less inclined to tolerate such a method of settling grievances. This may in part have been a result of the drawn-out and bloody conflicts with France. Countless brave men had lost their lives in defence of their country, and for one to shoot another in cold blood over petty squabbles was no longer a noble act.

Originally published in All About History 9

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!