The Italian dictator declared war on the Sicilian Cosa Nostra, but its suppression at home led inexorably to its rise in America

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

Benito Mussolini’s decade-long war on the Sicilian Mafia began with a perceived insult. In May 1924, the Italian Fascist prime minister swept into Sicily for a much-publicised visit, accompanied by an ostentatious military entourage of battleships, planes and even submarines. Arriving in Piana dei Greci near Palermo, he was met by mayor – and mafioso – Don Francesco Cuccia, who cocked a sardonic eyebrow at Mussolini’s phalanx of bodyguards and security and announced, “You are with me; you are under my protection. What do you need all these cops for?”

The furious Mussolini refused Cuccia’s hospitality, and the equally insulted Cuccia instructed his townspeople to boycott the dictator’s subsequent public address. Humiliated, Mussolini cut short his visit and Cuccia’s PR gaff went down in history as one the Mafia could have done without. He had drawn attention both to the Mafia’s power within Sicily and to its arrogance. Far from quietly allowing the Mafia to remain above the law, Mussolini resolved to crush them.

So the myth goes for why the Italian dictator decided to take on the Mafia. It’s a good story – and true – but there is, of course, more to it than meets the eye. Cuccia may have been the final catalyst, but the Mafia was already on Mussolini’s radar as a force that needed dealing with. Sicily had long been a law unto itself, and Mussolini, seeking to consolidate an ironclad dictatorship, risked being dangerously undermined if he allowed organised crime to survive on his watch. A successful campaign against the Cosa Nostra (the specific name for the Sicilian Mafia, which translates as ‘our thing’) would strengthen his rule.

A former journalist, military veteran and Socialist Party member, Mussolini had rejected socialism as a failed ideal by the end of World War I and formed his own ‘Fascio’ movement in 1919. The plural of ‘fascio’ is ‘fasci’ (meaning ‘bundle’ or ‘sheaf’), a word that had become the name of 19th-century workers’ movements, in which aggrieved labourers banded together against oppressive and unfair employers. Mussolini’s politics quickly gained traction in the economically depressed post-WWI Italy, via the notion that it was classless. Rather than focusing on socialism’s class war, his Fascism promised the eradication of class altogether, a unified society where class wasn’t an issue.

Fascism hadn’t quite at this point come as close to Nazism as it would during World War II but it was still deeply unpleasant, viewing black and Asian races as inferior to whites, and advocating imperial colonisation and racial segregation. But it didn’t champion the insistence on Aryan racial ‘purity’ of the Nazis. In a peculiar way, Mussolini’s Fascism was almost inclusive: he wanted to make more people Italian, endorsing the assimilation of populations surrounding Italy, such as Dalmatia, Albania, Slovenia, Corsica and others. The basic thrust was an Italy along the lines of the Roman Empire, including the good bits of the Italian Renaissance. “The Roman tradition is a powerful force”, ran Mussolini’s ghost-written book Doctrine Of Fascism. “Empire is not only territorial or military… but [also] spiritual and moral.”

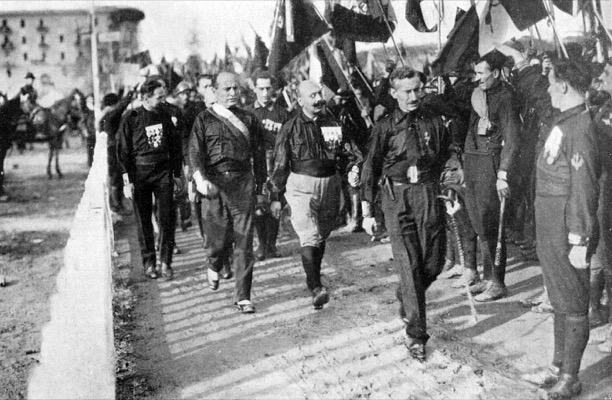

Mussolini came to power in Italy in October 1922 in a manner the Mafia would have approved of: through a display of power that was clear but not showy, a iron fist in a velvet glove. The Fascists had established paramilitary squads of disgruntled war veterans in 1919, popularly called the Blackshirts, whose job was to suppress socialist, communist and anarchist demonstrations. The Fascists officially became the National Fascist Party in 1921, and after 30,000 Blackshirts marched on Rome to demand the resignation of liberal Prime Minister Luigi Facta, Italy’s King Victor Emmanuel III asked Mussolini to form a new government.

After tolerating a couple of years of coalition, Mussolini gradually built a police state, writing into law that he was no longer answerable to the parliament. Parliamentary elections were abolished in 1925 and all other political parties were outlawed in 1926. Mussolini was essentially an untouchable dictator, but the South’s Mafia-led pseudo-independence remained a problem. “Italy wants peace and quiet, work and calm”, Mussolini pronounced. “I will give these things with love if possible, and with force if necessary.” Sicily was about to be dealt with.

Sicily in the early-20th century was not markedly different to the Sicily of the previous century; it was essentially still a feudal system, with peasant labourers working for wealthy landowners and estate managers who afforded them few rights and little pay. Many desperate peasants resorted to crime simply to survive, and with no police force at that time, the local elites began employing ‘companies at arms’ – often made up of precisely the type of bandits that would otherwise cause them trouble – to hunt down thieves and negotiate the return of stolen property.

Almost inevitably, these companies evolved into something more akin to protection rackets, as likely to collude with criminals than with their wealthy supposed employers. Cattle ranches and citrus orchards were particularly vulnerable to thieves and saboteurs and since the landowners could not be present on their vast estates at all times, the racketeers – first officially dubbed the Mafia in 1865 – began to wield considerable power.

The secretive mafiosi recognised each other by special signals, obeyed no law but their own, and operated a code of honour and silence (‘Omerta’) when confronted with legal authority: loyalty was key. Attempts by the pre-Mussolini Italian government to intervene only served to alienate the populace and make the problem worse. The Mafia in Sicily became increasingly powerful politically, manipulating elections to install their own favoured candidates. Along with the protection business there were murders, robberies, counterfeiting operations, kidnappings for ransom and the intimidation of witnesses.

While the violence was plentiful, there was also a strict code of conduct and a substantial fund for supporting the families of imprisoned members. The Mafia looked after their own; Sicily looked after itself. Following his fateful visit and encounter with Cuccia, Mussolini had had enough of the rebellious island. Only the eradication of the Mafia would bring Sicily in line with the rest of Italy. The man he chose to accomplish the task was Cesare Mori.

Mori, who would gain the nickname the Iron Prefect (‘Prefetto di Ferro’) due to the ferocity of his anti-Mafia campaign, had distinguished himself as an exceptional police officer during the late-19th and early-20th centuries. However, he had found himself ignominiously transferred from the Italian metropolis to rural Sicily in 1903 when he got on the wrong side of a politician. His earliest encounters with the Mafia began here, and over the next decade and a half he was lauded for his successes.

During World War I, more than 40,000 Sicilian civilians dodged the draft and fled to the hills, leading to a massive increase in banditry and cattle rustling, which Mori fought relentlessly, laying siege to villages and leading patrols at all hours across all terrains. But he remained aware that the people he was fighting were not the most dangerous aspect of Sicilian criminality. While he was promoted for his successes, he insisted that, “the true lethal blow to the Mafia will be given when we are able to make roundups… in prefectures, police headquarters, employers’ mansions and… [political] ministries.”

The Iron Prefect returned to the Italian mainland in 1920, initially serving as a senior police officer in Turin, and later as a high-ranking politician in Bologna. He was initially resistant to Fascism, treating the Blackshirt thugs like any other group of dissidents that needed slapping down, but when the Fascists seized power he found himself dismissed from office. Regrouping, he let it be known that he was coming around to the Fascists’ way of thinking and held Mussolini in strong personal admiration.

His previous experiences in Sicily made him the obvious candidate for Mussolini’s anti-Mafia agenda, and, having been recalled to active duty in Trapani in 1924, he was made prefect of Palermo in 1925, with powers over the whole of Sicily and a remit to terminate the Mafia. “You have carte blanche”, Mussolini told Mori. “The authority of the state must absolutely be re-established in Sicily. If the laws still in force hinder you, this will be no problem. We will draw up new laws…”

Mori’s approach was devastatingly simple: he would out-mafia the Mafia. In the most simplistic terms, the Fascist state needed to assert itself as the bigger, tougher gang, and Mori’s first shock-and-awe salvo in his Mafia war was a violent siege in the municipality of Gangi.

The siege brutally ushered in the year of 1926, beginning on 1 January and continuing for ten days. Police established a tight cordon with roadblocks of lorries and armoured cars, and this combined with the freezing, snowy cold, kept the Mafia bandits from leaving their hilltop town. Police and Blackshirts cut the telephone and telegraph wires and crashed through homes, rooting out criminals in hiding. Cattle belonging to suspected offenders were slaughtered in the town square; women and children were taken hostage as a ruse to flush out their wanted husbands and fathers, and some policemen even took to occupying bandits’ houses and sleeping in their beds – rumours of rapes were widespread. A town crier walked the streets banging a drum and declaiming an ultimatum that all fugitives from justice should hand themselves over to the authorities. The Blackshirts’ much-reported ‘interrogation’ techniques included forcing prisoners to drink castor oil or eat live frogs.

On 10 January, Mori arrived from Palermo to ‘liberate’ Gangi with great pomp and fanfare. Bands played, banners waved, speeches were made from the town hall balcony, and Mussolini sent his congratulations and a promise for continued action: “Fascism has cured Italy of many of its wounds. It will cauterise the sore of crime in Sicily – with a red hot iron if need be!” Iron Prefect Mori’s final tally at Gangi was the arrest of 130 Mafia fugitives and 300 of their accomplices. He was just getting started.

The same tactics were put into effect four months later in the region encompassing Bisacquino, Corleone and Contessa Entellina, sending his anti-Mafia police/Blackshirt thug force on a roundup that scored 150 more arrests including the high-profile mafioso Don Vito Cascio Ferro. Don Vito was sentenced to life in prison for an old murder charge in 1930, and died incarcerated in 1942.

As well as the roundups and the violence, Mori orchestrated show trials and public rallies at which people were cowed into declaring their support for the Fascists. In 1926 there was a ceremony where the attendance of 1,200 Palermo estate owners was ‘requested’, at which they were required to swear oaths of allegiance as a Catholic mass was performed and Fascist hymns were played. A year later the scene was repeated among the citrus groves of the Conca d’Oro, but the indiscriminate arrests also continued. By 1929, 5,000 people had been collared in Palermo and 11,000 in Sicily as a whole. Many who were stamped on by Mori’s boot were innocent, but it mattered little to him. Mori made it clear that helping or defending the Mafia amounted, in the law’s eyes, to being a mafioso.

One famous example of Mori’s uncompromising processes involved the theft of a donkey, which led to a paper trail of dodgy transactions connected to the lawyer and politician Antonino Ortoleva. The documents revealed little more than low-level political chicanery. Mori’s police force pegged Ortoleva as a significant Mafia Don though and imprisoned him with no opportunity for him to defend himself. Smear campaigns and kangaroo courts like this were rife. Trials almost always led to convictions, and Mussolini was particularly gratified when his Piana dei Greci enemy Don Francesco – “that unspeakable mayor” – was locked up.

Mori’s campaign of terror ended abruptly in 1929, as his support within the shifting allegiances of the Fascist party began to wane. The official line was that the Fascists had triumphed in Sicily and there was some justification for the claim. The murder rate had declined and most of the crime families had been broken up. “The Mafia hardly existed anymore”, said informant Antonino Calderone. “Mafiosi had a hard life. The music changed.”

Mafia crime may have declined, but it hadn’t been eradicated. The Italian press were instructed not to report on criminal activity in Sicily, to keep up the pretence that lawbreaking had been crushed forever. Show trials became a thing of the past, although in practice this just meant that criminals were now quietly dealt with without even so much as a cursory nod to the law. Mori’s war on the Mafia had done nothing to address the societal circumstances that had led to the families’ emergence in the first place. During the lull in criminal activity, landowners were able to increase their rent by thousands of per cent, again making anything more than basic subsistence untenable for the rural population. When the Fascist government fell during the chaos of the Allied occupation of Sicily during World War II, the reinvigorated Mafia was able to reassert its power on the island.

In temporarily suppressing Mafia activity in Sicily, Mussolini, Mori and the Fascists contributed to its rise overseas. Faced with long odds at home, many mafiosi fled to the United States, sowing the seeds of far darker and more powerful crime syndicates. The Mafia in Sicily had retained some semblance of being a brotherhood united against oppressors – although it should be stated that they could do their fair share of oppressing and were as likely to break strikes as support them – but in the States the Mafia became far more about simple profit. Chief among the Mafia expatriates were Carlo Gambino and Joseph Bonanno.

Gambino was born in Palermo and had begun carrying out execution orders for Mafia bosses in his teens. He fled to the States on a shipping trawler during Mussolini’s crackdown, and ended up heading the most powerful of the New York families. Bonanno was born in Castellamare on Sicily’s northwestern coast and headed to America on a Cuban fishing boat in 1924. Known affectionately as ‘Joe Bananas’, he led the Brooklyn-based Bonnano family, and was the longest surviving of any of the Sicilian exiles. His was the most Sicilian of the Five Families, to the extent that he and his compatriots continued to speak in the island’s unique Italian dialect – he was thought to be the primary inspiration for The Godfather’s Vito Corleone. Mussolini and Mori’s crackdown on the Mafia led to key members of the shady underworld exporting their particular brand of organised crime to the United States.

After Mori’s operations in Sicily were wrapped up, he became a marginal figure in Italian politics and died in obscurity in 1941, while his benefactor Mussolini steered Italian Fascism toward its final fall in World War II. Mori’s legacy turned out to be both significant and temporary. He had cowed the Mafia in Sicily, but failed to eradicate it. In the absence of Fascism’s iron fist, not to mention its Iron Prefect, the Mafia in Sicily would rise again to be just as powerful – if not more so – than they had been before. As Sicilian figures like Gambino and Bonnano stood on boat decks after month-long voyages, they surveyed the docks and distant skyscrapers of their new country and prepared to bring their Omerta to a new world.

Originally published in All About History 13

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!