Hero, archer, lover, poacher, murderer, thief, vagabond… The story of Robin Hood has taken many forms through the ages, but is there any truth in the legend?

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

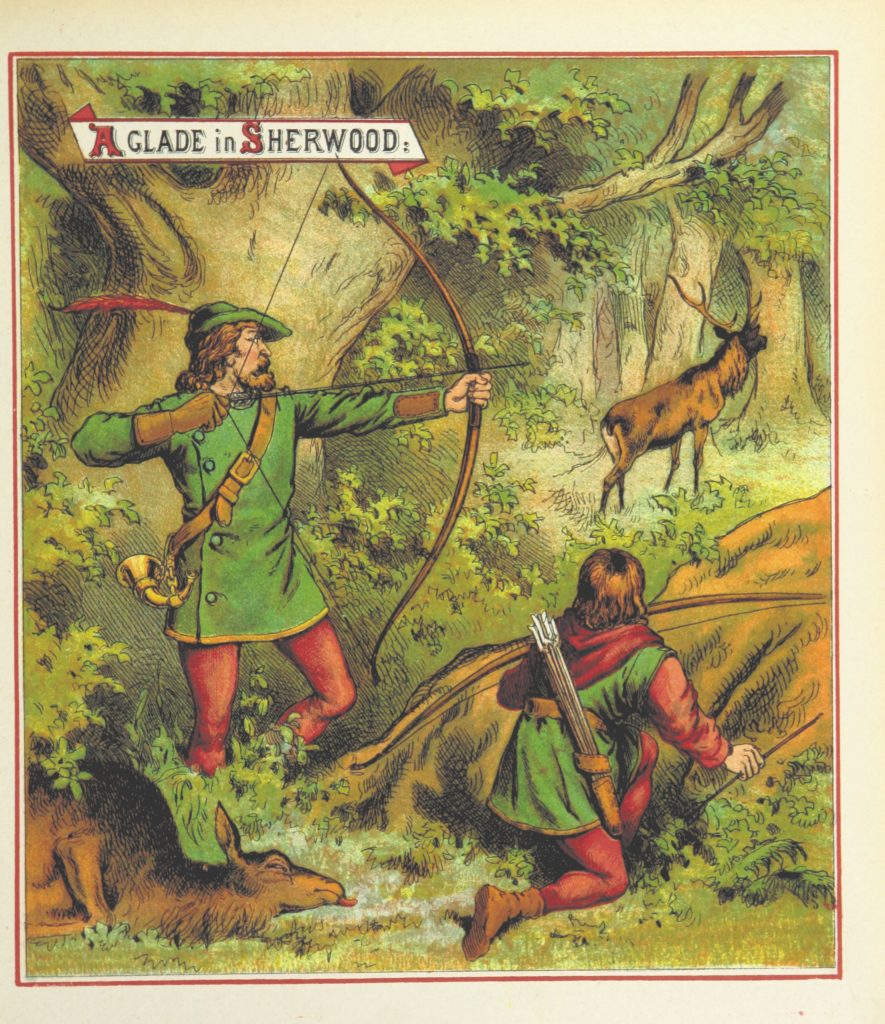

Robin Hood; maybe you’ve heard of him? Medieval lovable rogue-type chap with green tights, good with arrows (and women), lives in a hideout in Sherwood Forest with a band of jolly outlaws where they fleece greedy travelling rich folk of their cash under the threat of violence, before sending them packing. His generosity to the downtrodden is renowned and he’s loved by the common folk, hated by the wealthy and powerful and he’s a devil with the ladies, if you know what we mean – especially high-born damsels trapped in their metaphorical towers (or actual towers, depending on the story). He doesn’t see eye-to-eye with corrupt authority figures either but don’t think that Robin Hood is anything but a loyal and patriotic Englishman: everything he does, he does for his country and the rightful king, Richard I of England, who’s off fighting a noble crusade against evil heathens, thousands of miles away.

No one blindly believes the story of Robin Hood as we know it today, but long periods of English history have had a funny habit of recycling these tales until it’s hard to tell fact from fiction, or what the original truth was – if it wasn’t a complete fabrication to begin with. Like a giant, generational game of Chinese whispers, the legend of Robin Hood has been passed along the popular media of the times with a bit of embellishment added here, something considered dark, unflattering or politically unsavoury removed there. And so, via the 20th century’s communication revolution, it has boomed into world fame. In the last few decades we’ve been adding our own tint to this rose-hued tale of the arrow-slinging rebel, like the stories of Russell Crowe’s disaffected soldier, Kevin Costner’s noble Prince of Thieves and Errol Flynn’s jubilant swashbuckling rogue. If we’re going to sort some fact from fiction here, we have to unravel the Hollywood-spun Batman of the Middle Ages back to where it began, sometime in the 12th century, and look at the direct origin of today’s tale.

The legend himself, if not the tales, can be traced to the time of King John of England, who was born in 1166 and reigned from 1199 until his death in 1216. These ballads and stories were born and cultivated out of an era of social upheaval. The end of King John’s reign saw the English barony revolt and the signing of the Magna Carta, which was the first step along a long road to the breakdown of the ancient feudal system of government. While characters like Maid Marian appeared in tales from a later date, some of Robin’s band of ‘Merry Men’ can be clearly identified at this time, but things get a lot murkier when it comes to the titular hero.

According to one of the more recent theories backed by, among others, historian David Baldwin, Robin Hood’s real identity was that of a 13th-century farmer called Robert Godberd, whose escapades were far from the sugar-coated tales we see today. The crimes him and his band of outlaws around Nottinghamshire and nearby counties were accused of were of the brutal era in which he lived: burglaries, arson, assaulting clergymen and murdering travellers. The nature of their law-breaking has slowly been eroded throughout history to suit an increasingly gentile audience, compared with a medieval population accustomed to violence and who found Godberg’s activities entirely palatable. Godberg and his fellow brigands were in defiance of a tyrant who had an iron grip on the extensive forested regions of Nottinghamshire. King John enforced the enormously unpopular Forest Law, which allowed the royal court exclusive access to vast swathes of hunting grounds, with utter ruthlessness. Thus, morally speaking, Godberg’s actions were justified by the common man as necessary for the greater good of the people.

There are a number of other recorded Robin Hood-type characters with similar names and lives that span a period of 150 years or so during this time. The earliest is Robert Hod of Cirencester, a serf who lived in the household of an abbot in Gloucestershire. He murdered a visiting dignitary early in the 13th century, fled with his accomplices and was subsequently outlawed by King John’s reviled minister Gerard of Athee. Four other Robert Hods existed in 1265, at the Battle of Evesham during King Henry’s time. Each became fugitives and outlaws for various reasons, including robbing travellers and raiding an abbey in Yorkshire, which could explain how the character of Friar Tuck eventually made his appearance in later tales. Later versions, namely two Robyn Hods, appeared respectively as an archer in a garrison on the Isle of Wight and as a man jailed for trespassing in the King’s Forest and poaching deer in 1354. The name Robert was a common one around this time, while the surname Hod or Hode likely came from the old English word for a head covering. It’s also possible his surname was derived from the story of ‘Robin of the Wood’.

With the array of similar characters and names of people who existed at this time it’s not surprising that historians have trouble pinning the character’s origin on any one man. The earliest surviving ballads of the Robin Hood story don’t even elaborate on his exploits: they make no mention of the troubles of the time, Robin Hood’s cause or the years he was active, simply that he was an outlaw who lived in and around Sherwood or Barnsdale. To further confuse things, there are numerous accounts of outlaws in the 13th and 14th centuries adopting the name of Robin Hood and Little John, which suggests the story had achieved some popularity even then, although adopting the name of a famous outlaw – fictional or otherwise – was common among criminals at this time.

This Robin Hood had no spouse or family, no land and certainly no title. No reason is given for his criminality and his characteristics were likely drawn from some real-life outlaws of the time. One of the most telling aspects of these stories is the language they were written in: up until 1362, when Parliament decreed that English was to be used in court, French was widely spoken in the country – whereas even the earliest stories of Robin are in English, which helps establish a date.

By the 14th and 15th centuries, the tales of Robin Hood had gained some fame as they were disseminated in the traditional May Day festivities, while his story had begun to be written into plays and ballads. There’s no mention of the folk hero living at the time of King John, but he can be found in the 15th-century stories of Robin Hood and the Monk, The Lyttle Geste of Robyn Hode, Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne, Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar and Robin Hoode his Death. The plays Robin Hood and the Friar and Robin Hood and the Potter were written specifically for the May Day Games in 1560 and were based on earlier ballads of the same name. During this period, his Merry Men began to accrete together from various sources as Robin was embellished with details like so many layers of varnish. Word of the character had began to spread beyond the counties of the midlands and in the late-15th century, he is referred to in plays written as far afield as Somerset and Reading. He was well known even to the famous womanizing, warmongering king of England, Henry VIII, and his royal court. The young monarch’s idea of celebrating May Day involved walking into Queen Catherine of Aragon’s chambers with his nobles, “apparelled in short cotes of Kentish Kendal, with hodes on their heddes, and hosen of the same, every one of them his bowe and arrowes, and a sworde and a bucklar, like outlawes, or Robyn Hode’s men,” according to Hall’s Chronicle by Edward Hall, a 16th-century scholar.

By the late-16th century, the Merry Men had acquired a friar, Robin had a love interest and he’d also gained nobility. Playwright Anthony Munday wrote two plays on the outlaw, The Downfall of Robert Earl of Huntington and The Death of Robert Earl of Huntington, in which Robin (Robert) has clearly been lofted into high society. Or at least, it was his position to lose: in the plays, Munday makes Robin an earl in the reign of Richard I who is disinherited by the king. Fleeing into the Greenwood, he is followed by the daughter of Robert Fitzwalter, one of the leading barons who rallied against the king, where they fall in love and she changes her name to Maid Marian. King John, angry that his would-be bride has been stolen from him by an outlaw, pursues her in the second play and poisons her at Dunmow Priory.

The idea that Robin was a fallen noble and some kind of love triangle existed between King John, Maid Marian and Robin still endures in some stories today. But by introducing a lover and giving him blue blood, the Robin Hood of the 16th century makes the transition from a brutal and often murderous outlaw in defiance of the monarchy to a more domesticated hero, a protagonist the ruling classes could admire and relate to – someone with just cause against an evil ruler. His status as an outlaw had been relegated to a trait that added an element of drama to the story, rather than one that defined it.

From the 16th century onward, with the advent of the printing press, the story of Robin Hood becomes more refined and much more familiar. Across the next few centuries, the character and the stories would pick up traits and themes that generations to come would adopt when turning to their own adaptations. The 18th-century Robin Hood sees him encounter farcical situations. For example, the ballads of the time talk of a series of tradesmen and professionals getting the upper hand with the hapless outlaw, while the Sheriff of Nottingham is the only one to be bested by Robin. Robin dresses up as a friar in Robin Hood’s Golden Prize and cheats two priests out of five hundred pounds – nearly $16,000 (£10,000) in today’s money – before he’s caught and summons the Merry Men with his horn.

The Victorians, notorious for enamelling history with their own style and values, weren’t shy about leaving their mark on Robin Hood either. By the mid-19th century, the cost and efficiency of printing books was such that they had become available to the masses. US writer and illustrator Howard Pyle took the traditional folk tale of Robin Hood and adapted it to his own children’s version, serialising it into short stories called The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, which became enormously popular. His green-tights vagabond was a moral philanthropist who would go on to spawn a whole century of the people’s hero that took from the rich and gave to the poor.

By the time author TH White came along, the story of Robin Hood was among the world’s most well known. White took it a step further and, as an author made famous by his Arthurian novels, brought Robin Hood and his Merry Men into his novel The Sword In The Stone, which was made into an anthropomorphic Disney film a quarter of a century later.

The late-20th century and the booming phenomenon that was cinema brought with it numerous adaptations, most of which aren’t remotely faithful even to the 16th-century versions. The Sean Connery and Audrey Hepburn film Robin and Marian made much of the romance but for the first time, cast King Richard as a less-than-benevolent character. The Robin of Sherwood television series went as far as to add a Muslim character in the form of Nasir the Saracen, a trend the famous Kevin Costner film followed through Morgan Freeman’s Azeem.

The character of the lovable rogue has international appeal, so almost every country has its own version of Robin Hood: in Wales, Twm Siôn Cati is likened to Hood as a high-ranking highwayman driven to robbery as an income by his Protestant faith under a Catholic monarch. Ukranian rebel Ustym Karmaliuk made his name in the 19th century for robbing the rich and distributing the proceeds of his crimes to the poor, and over a millennium before Robin Hood came to the fore, Boudicca, queen of the Iceni, defied the Romans when they forcibly took control of her lands and people. She led a successful revolt that destroyed a Roman legion and the Roman capital before it was put down. Almost every generation has a story that is similar to Robin Hood, illustrating the very human desire and need to have a figure who stands for right against wrong, light against dark.

Given that nearly a millennium has passed since the first tale of Robin Hood was told, in addition to his murky origins that even 13th-century bards cannot agree on, it’s unlikely any historian will be able to settle on who Robin Hood and his Merry Men were exactly, or what little truth there is to their deeds. As far as history is concerned, the Robin Hood legend has become a victim of its own popularity, obscured by generations of storytelling taking it firmly into the realms of fantasy.

Originally published in All About History 9

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!