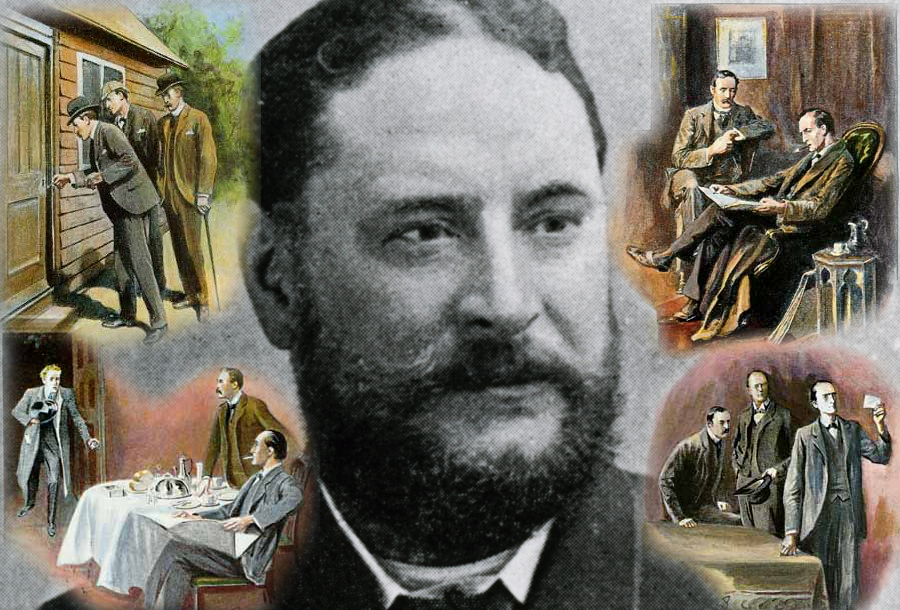

A master of disguise and an expert in deduction, Detective Jerome Caminada pursued criminals relentlessly through the dangerous underworld of 19th-century Manchester

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

It was the dead of night and Detective Chief Inspector Jerome Caminada of the Manchester City Police was deep undercover, on the trail of one of the most desperate felons he had ever encountered. Robert Horridge, an unscrupulous burglar hardened by time behind bars, had gone too far, so Caminada was preparing for a final confrontation. Both men were carrying firearms, but only one could walk away unharmed from a battle that would test the skills, courage and determination of the police officer to the very limit.

Disguised as a labourer, Caminada had begun his search for Horridge at the Liverpool docks. The year was 1887 and the dockside was quiet, with most of the workers in their homes or the local public house. He had only a few hours of darkness during which to complete his dangerous assignment before the shipyards and warehouses came back to life at dawn and people began to spill out onto the streets. Another undercover police officer working with Caminada whispered to him that a suspicious-looking character had just cast a hard stare in his direction. Caminada peered through the shadows and recognised his sworn enemy by the gait of his walk, heading toward the Prince of Wales public house. The detective had one chance to net his prey and put an end to the violent thief’s long reign of terror. Horridge had already shot two policemen and Caminada knew that he was walking a tightrope – one slip would result in his own death.

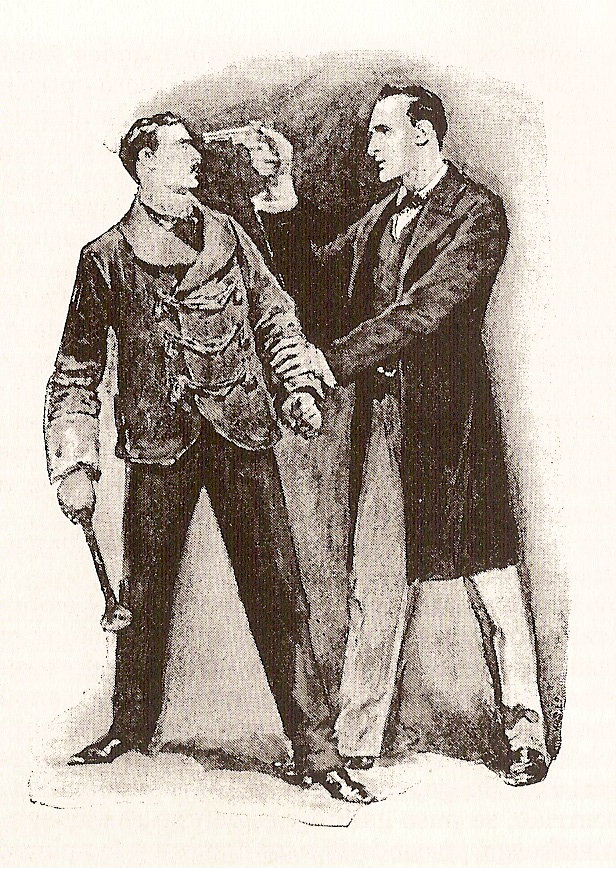

His heart racing and beads of perspiration forming on his brow, Caminada took a deep breath and ran silently over to his quarry, seizing him by the arms. As Horridge reached into his pocket for his firearm, Caminada drew his revolver and, with the weapon at full cock, placed the muzzle to the felon’s mouth saying, “If there’s any nonsense with you, you’ll get the contents of this.” After a violent scuffle, Caminada subdued Horridge with a blow to the head with the butt of his revolver and dragged the prisoner to the local police station. When he was searched, a fully loaded six-chambered revolver was found in his pocket. Detective Caminada had had a near miss and after two decades of pursuing his real-life ‘Professor Moriarty’, he had finally defeated him.

Detective Caminada and Robert Horridge had first encountered each other in 1870 when Caminada was a police constable. Horridge had stolen a watch from a gentleman near Victoria Railway Station in Manchester and the young police officer had traced the watch to a local watchmaker’s, where the thief had left it for repair. When Horridge came to collect it the following day, Caminada was waiting. He arrested the thief, who was sentenced to seven years’ penal servitude due to previous convictions. As he was sent down, Horridge vowed that he would kill the man who had put him in prison.

After his release, Horridge wasted no time in resuming his criminal career and committed a string of offences and terrorised the streets of Victorian Manchester for the next 20 years. He would stop at nothing to preserve his freedom and whenever the police were on his tail, he undertook daring escapes to evade arrest, including breaking through the ceiling of a house to flee through the lofts of adjoining properties and diving into the River Irk. After a second long stretch in Pentonville Prison, Horridge was determined to get even with his lifelong nemesis.

The final showdown began in the small hours of 30 July 1887, when Horridge was disturbed by a passing policeman while robbing a shoe shop. With the bloodcurdling words, “I will not be taken alive”, Horridge shot the officer. Luckily, the bullet only grazed the constable’s neck but when a colleague came to his assistance he was not so fortunate; he received a gunshot to the chest. Horridge fled and the chief constable turned to the only man who could run this deadly felon to ground: Detective Jerome Caminada. Despite their rivalry, the two men were not so different; they were the same age and had both grown up in the worst rookeries of Victorian Manchester where they survived difficult childhoods where the odds were stacked firmly against them.

Jerome Caminada was born in Deansgate, Manchester in 1844, to parents from immigrant families that had arrived in the city in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. Jerome’s father, Francis, was an Italian cabinetmaker and his mother, Mary, a textile worker with Irish roots. The couple had already lost one child to disease and when Jerome was just three years old, his childhood was shattered by a double tragedy. In 1847, Jerome’s eldest brother died of enteritis, aged just nine, and three months later he lost his father to a heart disease. Mary Caminada and her surviving four children were forced to move into Manchester’s dark underworld where their fortunes declined further. Jerome’s mother had two illegitimate children who both perished in infancy, and shortly after, his older sister Hannah died in the workhouse at the age of 15. Despite the trials of his early life, Jerome attended school and after a brief spell working in an iron foundry made the momentous decision to join the Manchester City Police Force as a constable, aged 23. As he set out on his career of fighting crime on the streets of his city, his first-hand knowledge of the nefarious characters lurking in the seedy neighbourhoods in his city would become his most effective weapon.

Manchester was one of the most dangerous places in Victorian England. The Industrial Revolution had brought tremendous wealth for factory owners and businessmen, but the reality for thousands of workers was long hours of toil in unbearable conditions, with poor housing and barely enough money to feed a family. Disease was rife and crime endemic. By the time PC Caminada had begun to walk his beat, the crime rate was a staggering 1.86 crimes per capita – four times higher than in London during the same period.

The streets of the city were teeming with thieves, crooks and prostitutes, and on every corner were illegal beerhouses, gambling dens and brothels. In the streets, behind the fashionable shops and luxury hotels of central Manchester, lurked swindlers and con artists ready to relieve unwary shoppers of their money and valuables. Professional cadgers implored passersby with their stories of woe: crippled soldiers, out-of-work colliers and destitute sailors, none of whom had ever seen a battlefield or the sea, or been down a mine. Hired children cried pitifully and distraught women called out to well-dressed gentlemen for help. Those tempted into the shadows would be robbed, beaten and, in the worst cases, garrotted. Official police returns confirmed the high level of crime and in 1870 the number of arrests had reached over 26,000, with theft and pickpocketing the most common offences, but only five per cent of arrests resulted in conviction. The police clearly had its work cut out and the young PC Caminada would eventually step out of his police uniform to walk the crime-infested streets undercover to tackle the appalling crime statistics.

Within his first week on the beat, Jerome Caminada was insulted and assaulted but brushed these instances off and soon demonstrated an exceptional aptitude for detective work. When he was just a year into the job, he masterminded an operation to apprehend a gang of violent thieves. A valuable collection of meerschaum pipes had been stolen from a private house and the only information was a description of the prime suspect’s ‘striped, shining, cloth trousers’. Nicknaming him ‘Shiny Trousers Jack’, it took Caminada just a week to track down his suspect and, locating him in a cellar dwelling, he organised an early-morning raid. It was a bitterly cold night with hardened snow on the ground, so as Caminada crept up to the lodging house, he removed his boots so he wouldn’t be heard by the dangerous gang, one of whom was a skilled prizefighter. Spying on the suspects through an open shutter, he spotted a deadly carving knife on the table. After sending his officers into a nearby alley, he masqueraded as a member of the gang to gain entry. As they opened the door, he rushed in, armed only with a staff and a bull’s-eye lantern, grabbed the knife and handcuffed the gang before his colleagues ran in behind him. Soon afterward, Jerome Caminada was promoted to detective.

The new detective’s first cases included tracking pickpockets at racecourse meetings, exposing the insidious practices of quack doctors and infiltrating some of the most complex swindles of the time. During his early investigations he developed the groundbreaking techniques that would link him in the minds of the contemporary public with the newly penned stories of Arthur Conan Doyle. He regularly went undercover, donning a range of disguises, usually that of a labourer or factory worker. At the Grand National his disguise was so convincing that his own chief constable failed to recognise him and almost arrested him for the theft of a watch he had recovered from a pickpocket. On another occasion, he pretended to be a travelling salesman with a limp to confront a fake doctor.

Caminada used his encyclopaedic knowledge of the criminal fraternity that inhabited the sordid neighbourhood of his childhood to arrest thieves, swindlers and thugs. By night, like his fictional counterpart, he wandered the closed courts and dark alleyways, and by day, he visited the prisons to gather intelligence for his casebook. He even had a network of informants, his own Baker Street Irregulars, with whom he exchanged information over a pint of ale in a disreputable tavern or on the back pew of the Hidden Gem, a Catholic church tucked away between office blocks and warehouses in the heart of the city.

When Sherlock Holmes made his debut in A Study In Scarlet in 1887, Detective Caminada was at the top of his game. Earlier that year he had rid the streets of Bob Horridge and arrested the Birmingham Forger, wanted in several cities for a fraud amounting to almost £750,000.

Two years later, Caminada would need all the brilliant deductive powers of the iconic consulting detective to solve his most baffling case yet: the Manchester Cab Mystery. On the evening of 26 February 1889, a businessman hailed a hansom cab on the steps of Manchester Cathedral in the company of a young man. Just over an hour later, his companion had fled and 50-year-old John Fletcher was slumped unconscious in the cab. The driver took him straight to Manchester Royal Infirmary, where he was certified as dead on arrival. Already horrified by the recent gruesome murders of Jack the Ripper in the East End of London, the public woke the following morning to the shocking news that a respectable paper merchant had been found dead in a cab. To avoid mass hysteria, the chief constable placed the perplexing matter in the capable hands of Detective Caminada. It was one of his most puzzling cases; there wasn’t even any evidence that a crime had been committed.

There were no signs of violence on John Fletcher’s body and the initial report of the hospital surgeon suggested that he had died of alcohol poisoning – he was a habitual gin drinker – following a lethal mix of alcohol and chloral hydrate, a chemical taken to combat insomnia. At the time of his death, Fletcher had no money on his person and his expensive gold watch was missing – signs that a crime had been committed.

Initial enquiries established a physical description of the unknown companion: he was about 22 years old, 157 centimetres (5 feet 2 inches) tall, clean-shaven and was wearing a dark-brown suit and a chimney-pot hat. Caminada deduced that the crime was linked to illegal prizefights, as chloral hydrate was used to subdue opponents in the ring and therefore to rig the betting. His questioning of local lawbreakers soon yielded a possible suspect: 18-year-old Charlie Parton, an innkeeper’s son, known for drugging his customers. Information about the theft of a bottle of chloral hydrate from a chemist’s in Liverpool – Parton’s home city – confirmed his instincts. Caminada knew he had his man.

The chemist identified Parton and, on 2 March, Caminada arrested his prime suspect. Shortly afterward, two previous victims came forward, alleging that Parton had drugged them too, in an attempt to rob them during a night out. The net was closing, but Detective Caminada still had one more card to play. In an astonishing twist, he located a key eyewitness who had seen Parton pouring liquid from a vial into Fletcher’s beer in a public house on the night of his death. This compelling evidence secured Parton’s conviction for murder and, in the record time of three weeks, Detective Caminada had solved the case and brought the perpetrator to justice. Parton was sentenced to death – later commuted to life imprisonment – and the sensational climax of the Manchester Cab Mystery was widely celebrated in the national press. Jerome Caminada became a household name and earned his reputation as ‘Manchester’s real-life Sherlock Holmes.’

Detective Caminada fought crime tirelessly for another decade after that. In his memoirs, published toward the end of his career, he revealed he had been working undercover on covert missions for the newly formed Special Irish Branch of Scotland Yard, in an effort to track Irish nationalists throughout Europe and America. These dangerous operations required all his skill and cunning and, in one case, he shadowed a Fenian suspect to Paris after lifting an address from the imprint on a blotting pad in an informant’s cottage in Cheshire. The head of the CID, Chief Superintendent Frederick Adolphus Williamson, praised Jerome Caminada as one of only three “real detectives” he knew.

Back home in Manchester, Caminada was promoted through the ranks of the Manchester City Police Force, ultimately to the lofty position of detective superintendent. During his dazzling career, he investigated many high-profile cases on behalf of Scotland Yard. He was even captivated by a beautiful and expert forger, Alicia Ormonde, who was herself something of a real-life Irene Adler. On the streets of his city, he faced belligerent anarchists campaigning for freedom of speech, as well as the notorious gangs of ‘scuttlers’ (street-fighters) and even managed to save a wrongly convicted young man from the gallows on one occasion. After his retirement from the police force in 1899, the worlds of fact and fiction merged almost completely when Caminada became a private inquiry agent whose great detective skills were available for hire at the right price.

A full century after his death, Caminada is still considered to be one of the finest detectives in the history of Great Britain. He was a true Victorian super-sleuth who patrolled the streets of one of the country’s most dangerous cities, tracking down criminals using a mixture of disguises, a network of contacts, knowledge of science and sheer wit and bravery. Whether through Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s creation or a host of different fiction and nonfiction writers, his legacy will not be forgotten.

Originally published in All About History 13

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!