The capital of Africa’s Benin Empire astonished Europeans with its beauty, so why is there nothing left?

“Great Benin, where the king resides, is larger than Lisbon; all the streets run straight and as far as the eye can see,” wrote Portuguese ship captain Lourenço Pinto in 1691. He added, “The houses are large, especially that of the king, which is richly decorated and has fine columns. The city is wealthy and industrious. It is so well governed that theft is unknown and the people live in such security that they have no doors to their houses.”

Located in the depths of the jungle but connected to other African kingdoms and the Atlantic Ocean by the Niger River, Great Benin City was the imperial capital of an empire that, at its peak, stretched from Lagos in the west to beyond the Niger in the east – an area that equates to approximately one-fifth of modern-day Nigeria.

Benin made contact with Europeans in the 1480s when Portuguese traders happened upon it while seemingly trying to find a way around the traditional Sahara trade routes. Dutch merchants arrived 100 years later and, over next 200 years, more traders came from England, France, Germany and Spain. They all returned home with amazing stories to rival Pinto’s but today, if you mentioned the Benin Empire to a Westerner – even someone from Portugal, which maintained regular contact with the kingdom for 400 years – they are likely to stare at you blankly. So what happened to the great city of Benin and why did it disappear without a trace?

The beginnings of Benin

According to the oral history of the Edo people, Benin was originally called Igodomigodo, named after Igodo, founder of the Ogiso (meaning ‘rulers of the sky’) dynasty. Although Igodomigodo would go onto have around 31 Ogiso rulers who governed a formidable kingdom, the Benin Empire didn’t begin in earnest until the 12th century.

After years of political discord, Igodomigodo sent emissaries to the neighbouring kingdom of Ife to ask Oduduwa, the father of the Yoruba, for one of his sons to be their ruler. Oduduwa sent his son Oranmiyan and he became the first Oba, or king. He had a son, Eweka, but Oranmiyan found it hard to rule and he eventually renounced his position, saying that the politics of the people made his leadership intractable.

Oranmiyan called Igodomigodo “ile Ibinu”, or land of anger, and left Eweka behind with palace guardians to instruct him in the art and mysteries of the Benin so he could govern his own people. Eweka’s eventual reign started the Oba era. Oba Ewedo, who took over after Eweka’s death in 1255, changed the name of the kingdom from Ile Ibinu to Ubini and it was later contact with the Portuguese that changed the name again to Bini, from which we get the name Benin.

With the Oba established, the social hierarchy of the Benin Empire began to take form. Apart from the king, the political elite consisted of the titled chiefs – the Uzama n’Ihinron – and the royal family. The Uzama were powerful, and their role in customs and royal administration was gnomic. There were also the palace chiefs who oversaw palace administration, and the town chiefs who carried out regular administrative work such as tribute collection and the conscription of soldiers. Other officials carried out various duties that ranged from hunting to astrology while there were also craftsmen who were like a caste – guilds of artists produced art for the king and his royal court.

Imperial golden age

Imperial golden age

Between the late 13th century and the 15th century, Benin’s empire grew sporadically under the expansionist wars of conqueror kings. The fascination with and the formidability of the empire are built around various historical artefacts such as the impressive range of artworks, their advanced trading networks and the military strategies by which the warrior kings expanded and defended Benin. Benin had a large army of well-trained and disciplined soldiers, and the king was the supreme ruling authority over them.

Oba Ewuare I, who reigned between about 1440 and 1473, is largely credited with the transformation of the kingdom into a modern state structure. He reorganised the political structures through reforms that minimised the uneasy relationship between the Oba and the chiefs, and it enabled him to monopolise military power with the latter factor being responsible for his imperialist expansion. He is also noted for promoting art and artefact production – namely the bronze casting, ivory and wood that Benin would be known for around the world.

The craftsmen produced a distinct style of art that included heads, figurines, brass plaques and other items of royal adornment. Artistry was used to celebrate royal omnipotence and to legitimise the king’s power and glory. As the Oba was believed to embody the country and its continuity, art was used to communicate his divinity and possibly to also subjectify his people who rarely saw or had access him as he was believed to be a divine being.

Oba Ewuare was also associated with architectural innovation, city planning, grand festivals and the introduction of royal beads. He built on the efforts of Oba Oguola and completed the first and second moats, a network of ramparts that walled the city against external aggressors. The moat was an impressive part of national defence covering roughly 16,000 kilometres and enclosing 6,500 square kilometres of community land. It was built over the course of six centuries and it was a work of pre-mechanical engineering marvel.

In 1974, The Guinness Book of World Records described the Benin Moat as the largest earthwork in the world prior to mechanical inventions and it is considered to be the largest man-made invention, second only to the Great Wall of China. Oba Oguola was also believed to be the one who first sent his craftsman, Igueghae, to Ife to learn the art of bronze casting.

Iconic art

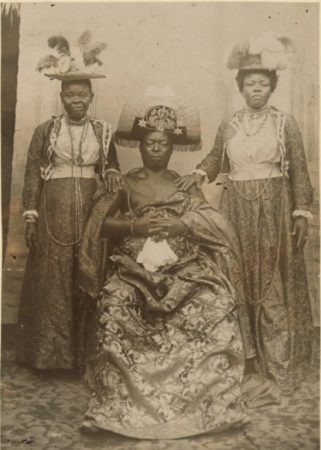

Of the many artworks from the Benin Empire, two of them are iconic: The Bronze Head of Queen Idia and the Benin ivory mask. The Bronze Head is a dedicatory piece in honour of Queen Idia, the mother of Oba Esigie, the king who reigned in the early 16th century. Queen Idia was the first Iyoba, or Queen Mother, and she played a hugely significant role in his kingship.

As Iyoba, Idia was a titled chief in her own right and she had a district, Iyekuselu, where she presided. She could raise the levies necessary to fund the army she oversaw. Although women were typically banned from certain professions – the army included – she went to war and recorded numerous victories. She was described as both possessing military acumen and sorcery with which she helped her son Esigie to defeat his brother Arhuanran, a contender for the throne.

As she was the king’s mother, the Iyoba already commanded prestige. But Idia revolutionised the position, allowing future Iyobas to wield actual political power. The position demanded, among other qualities, the holder to possess metaphysical power to help her son overcome other contenders to the throne. Queen Idia was said to have magical healing powers, and was depicted in many sculptures and art works commissioned in her honour, such as the Benin ivory mask. This was a small-scale ivory sculpture, made in honour of Idia. The mask was worn as a pendant by Esigie.

Today, the mask is a stark reminder of the unsavoury circumstances in which artworks left the shores of Africa. The mask was chosen as an emblem of FESTAC ‘77, a festival that took place in Nigeria and drew people from every part of Africa to celebrate black culture. The Nigerian government tried to secure the mask on a loan from the British Museum, which refused claiming that it was too fragile to transport. The Museum also requested a hefty $3 million as an indemnity. A sign that things might be improving, last year the British Museum held talks to discuss the return of the Benin Bronzes.

Bloodthirsty demise

Portuguese explorers made contact with Benin in the 15th century and they quickly started trading. The relationship between Portugal and Benin was so cordial that Oba Esigie was said to have sent ambassadors to Portugal, an exchange that resulted in European influences on Benin’s art and culture.

Esigie was reputed to have been literate in Portuguese and this boosted his interaction with the Portuguese traders. Meanwhile, the initial Portuguese missionary effort yielded some fruits as some churches sprang up in Benin. Trade continued between Portugal and Benin, with items including ivory, pepper and a limited supply of slaves.

During this period, there wasn’t really a major drive for a slave trade, because it was mainly women were sold into serfdom in Benin. Those who were enslaved – either because they were captured in war or forced to pay off their debts with hard labour – were arguably held more for the royal court’s prestige than actual economic proceeds. Trade in slavery was therefore marginal, as enslaved men were more useful to boost Benin’s military might than as a means of exchange. Besides, Benin was enjoying such an economical and military high that they didn’t need the proceeds from the Atlantic slave trade. It’s also worth noting that Benin’s relationship with the Europeans went beyond trading goods to warfare and mercenary services.

But by the 17th century, the kingdom had begun to decline as a result of a lack of leadership, internal fractures and indiscipline among members of the ruling class. When the slave trade was abolished and the price of ivory fell, it hit Benin hard. In the mid-18th century, the empire got a boost under Oba Eresonyen but it was not to last. The kingdom was starting to shrink as former territories began to move away from the old empire to towards the British both for trade and protection.

In the mid-19th century, Benin began to trade in palm oil and as the product became more important to the British, they sought to make Benin a protectorate. The Oba took refuge in isolationism and since Benin’s political power had declined, the king took to making human sacrifices to reignite his sacral authority. In 1892, vice-consul HL Gallwey pushed Oba Ovoramwen to sign his now diminished empire to the British as a protectorate. There was some doubt about whether the Oba indeed signed the treaty as he was unsure if the British had good intentions. By making Benin a British protectorate, the treaty would have facilitated commerce, ceased slave trading and ended human sacrifice.

Benin eventually fell during the punitive expedition of 1897. The Oba sensed that the British intended to depose him so his chiefs, against his knowledge, ordered a pre-emptive attack on a caravan carrying unarmed British officers. Two of the officials managed to escape but that incident sealed Oba Ovoramwen’s fate. Realising that his kingdom would be invaded, he ramped up the rate of human sacrifices to appease his ancestors.

The news of the Oba’s increasing bloodthirstiness, coupled with the deaths of the British officials, became a justification for the invasion of 1897 and Britain summoned its forces to descend on Benin. The Oba, his chiefs and their followers fled, although they came back and eventually surrendered. The Oba apparently approached the British with the pomp and pageantry of his position but he was humiliated and deposed. He was eventually sent to exile in Calabar, in the southeastern region of Nigeria, where he died in 1914.

Setting out to destroy what remained, the British set Benin on fire – but they moved the royal treasures to a safe place first. They sold some of the priceless artefacts in Lagos and transferred others to Europe, where they made their ways into private collections and museums. The sales were meant to cover the cost of the expeditions. In 1914, the throne was restored to Eweka II, Ovoramwen’s son, although under the supervision of the British colonial officers. What was left of Benin was nothing but a shadow of its former glory and today no signs remain of its mighty walls or moats.