World War II tore homes and families apart, but Britain would rise stronger than ever

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!

World War II placed an almighty strain on the population of Britain. Bombing, rationing, food and fuel shortages, families fractured by men and women away in the armed forces or undertaking war work and children evacuated to safety meant that many, on the home and battle fronts, idealised home life. The legacies of war resulted in many finding their dreams of home and family hard to attain in the post-war world. It wasn’t just buildings that needed to be rebuilt.

The announcement that war in Europe was over was greeted with much excitement; Joan Carmichael recalled:

VE day came after I had been working in Bath for just over a year. With some friends from the office, including the boss and his wife, we all rushed down to the centre of Bath and found a nice pub, where we had a celebratory meal and lots of drinks.

Later in the evening we joined the crowds dancing around Bath Abbey until the small hours. Someone suggested going to London to celebrate there, so we caught the early morning train with a two-hour journey to Paddington and somehow – tube, taxi, walking, I cannot remember – we made our way to St Paul’s, the symbol of Britain surviving the Blitz. Hundreds of people were walking around.

VE day was not the end of hostilities – the British army was still involved in conflicts in the Middle and Far East. Many men and women were stationed in Europe and the majority of those in the fighting forces were not demobbed until 1946, by which time they had contributed to electing a Labour government. The transition between war and peace was fuzzy. For many their dream of ‘happy ever after’ life was delayed. Barbara Cooke met her future husband on a train in 1944 and they continued their courtship by mail, meeting occasionally when he was on leave. When he received orders of an overseas posting, they set the date for their wedding – 7 May 1945.

The wedding dress was a collection of coupons that everybody collected together and the dress was bought from John Lewis in Leicester for the grand sum of £16. The dress was made with plain heavy white satin. Around four o’clock it came over on the radio; the newscaster announced that the hostilities had ceased, making me the ‘last wartime bride’. Along with our wedding telegrams came one for my husband, Tom, to return to his unit immediately.

Two and a half million couples were apart for long periods of time between 1939 and 1946. A third of a million merchant seaman, servicemen and women and 67,635 civilians had been killed; for some there would be no return to normality. James Teather met his future wife, Marjorie, when he was wounded and she was a nurse at Longdon Hall, Staffordshire, and they were married in 1943. In October 1944, Teather was killed over Belgium and her son recalls how in 1945 she found “her plans for the future destroyed by the war. Widowed and a single mother at 22.” However, 18 months later she met and married another RAF hero and they remained together until his death in 1994.

The return of many men from the armed forces was tinged with the anxiety they felt about their wives’ behaviour during their absence. Wives, mothers and sweethearts were emblems of the homes and country that the war was fought to protect; nevertheless, questions about whether women were worthy of men’s sacrifices lurked at the back of some soldiers’ minds. The high number of foreign troops that were stationed on British soil and Nazi propaganda that suggested American troops were ’lend-leasing’ British women had not assuaged their concerns. Nor did the News Of The World’s almost weekly coverage of stories of violent incidents caused by returning servicemen’s discovery of their infidelity, which accompanied the forces’ demobilisation.

Some men and women faced moral dilemmas about whether to disclose wartime misdemeanours. During the conflict, women’s magazines advised wives against undermining men’s morale by confessing to extra-marital affairs. Sometimes the consequences of a wife’s infidelity were clear for all to see, and married women who found themselves pregnant in their husband’s absence became a new group of mothers with illegitimate children.

The atmosphere of sexual suspicion could be acted upon speedily, thanks to the quickie divorces available to those in the forces. Divorce petitions in England and Wales leapt from approximately 9,970 in 1938 to 24,857 in 1945, and reached a post-war peak of 47,042 in 1947. Men who discovered their wives had been unfaithful initiated two thirds of them. At least, this was the reason given. It was in a couple’s financial interests for the husband to take on the role of injured party if he was in the forces, to gain a cheap divorce. For some couples it may have been a mutual decision, given the speed of some marriages at the outset of war and how many years and experiences had followed the nuptials.

Reconstructing fractured, tentative family units was emotionally taxing, although both the radio and women’s magazines were full of advice for women about how to create the perfect post-war home and family. Woman’s Hour was introduced in 1946, when television also returned with TV cooks Philip Harben and Marguerite Pattern. In practice, many families felt estranged from one-another. Douglas Wood, who had been evacuated to Staffordshire, found it difficult to re-adjust when he went home. He recalled:

Well, it was very difficult actually because I didn’t have any affinity with my family. When my father eventually came back from the war, he was then working night shifts cleaning buses. My mother was working shifts on the buses as a bus conductress and there was my brother, my sister and myself who were left to our own devices a great deal of the time. We were still relatively young of course, and, you know, it was quite a violent household and quite a poor household, it was a shame really but the contrast to me was really unbearable, the contrast to what I’d been so used to. And I didn’t have a Birmingham accent.

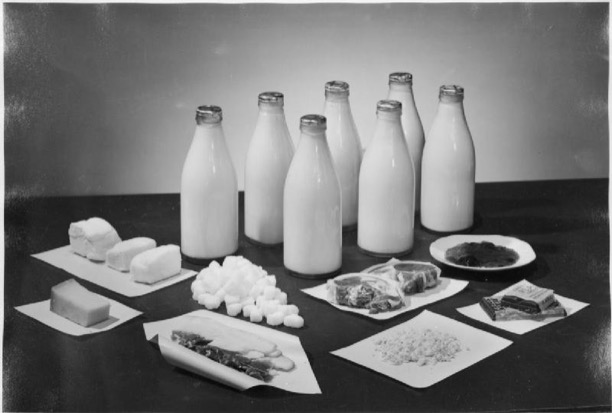

The problems were exaggerated for many families by difficulties in finding suitable places to turn into a home. Although St Paul’s Cathedral had survived the blitz, hundreds of thousands of houses across the UK had been destroyed and damaged. The British economy faced crippling debts to the USA and a balance of payments crisis. The austerity measures, shortages and more severe rationing that followed VE day meant rebuilding Britain proved a much slower process than many had imagined. During the war, damages to houses were addressed – tiles and slates were replaced, tarpaulins and plumbing improved and more than two million houses repaired by 1944 – but the doodlebugs of 1944 and 1945 destroyed more homes.

Government policy was to prioritise repairing the already-existing housing stock before building new houses; by the end of 1946, 85 per cent of necessary house repairs were completed. This approach – given the severe housing crisis, scarcity of resources and skilled labour – was rational; however, men returning from war looking forward to a home of their own, and seeking to start a new life with their wife and family, found the situation disappointing. Paul Baker recalls his father:

I was due to come home from Italy in 1945 but at the last minute his troop’s ship was diverted left on the Med instead of going right through Gibraltar to Greece to fight the EOKA terrorists in Athens. So, in fact, he didn’t come back until 1946, so when he came back into Coventry, he’d actually been crossed off the council house waiting list and he felt very bitter about that, because he was coming back and saying: “Well I’ve just come back from the war.”

In the struggle to find a home, many lived in one of more than 50 per cent of rural homes with no piped water to the house or lived in overcrowded late 19th and early 20th-century urban housing, which desperately needed updating. In London, Victorian and Edwardian houses were divided into rented rooms with numerous families often sharing a single sink and toilet. In exasperation and desperation, tens of thousands of people, including many ex-servicemen, moved in August 1946 into empty military camps around Britain – including Drayton Bassett in Staffordshire. The squatting movement spread to hotels and empty apartments around Britain, some staying a few weeks, others staying for many years.

Nellie Rigby, who married ex-RAF serviceman Rob in 1946, was luckier. After living for a couple of months in the Wavertree area of Liverpool with her husband’s sister and family, she remembered that: “In May we got a letter to say we have been awarded a prefab. And we was so thrilled.” Prefabricated bungalows, or ‘prefabs’ as they were called, were supposed to be temporary and last for only ten years, but actually remained much longer and were immensely popular. These aluminium bungalows were planned during the war to deal with the expected post-war housing shortages. A prototype was exhibited outside the Tate Museum in 1944 and it was met with approval. Consequently, Churchill announced plans for half a million to be built.

Prefabs were made in factories that had previously produced wartime aircraft. German and Italian Prisoners of War assembled those on the Excalibur Estate, in Catford, southeast London, from 1945 to 1946. Eddie O’Mahony was one of the first to move into this estate after his return from serving in Singapore. He was initially unconvinced, but his wife Ellen was delighted by the fitted kitchen, indoor bathroom, fireplace, boiler and fitted cupboards. The detached two-bedroom properties had their own garden and were painted throughout in magnolia. They were nicknamed ‘the people’s palaces’. However, rising production costs and the Labour government’s desire to build permanent homes of high standard meant that fewer than 160,000 were completed. Instead, in 1946 the government introduced the New Towns Act, which initiated developments in Harlow, Crawley, Hemel Hempsted and Stevenage in the 1950s.

The rebuilding of Britain was not just about creating homes, it also required schools and hospitals. The 1944 Education Act raised the school leaving age to 15, but improvements were hampered by a shortage of teachers and appropriate buildings. The need for greater speed in new school buildings was one of the main themes of the National Union of Teachers’ Annual Conference in 1946, when the president stated that: ‘Three-quarters of the schools in the country do not comply with the ministry’s new building regulations.” But one of the real successes of post-war Britain was the National Health Service. After many months of political wrangling to persuade doctors to participate, on 3 July 1948, the Daily Mail announced that:

On Monday morning you will wake up in a new Britain, in a state that ‘takes over’ its citizens six months before they are born, providing care and free services for their birth, for their early years, their schooling, sickness and workless days, widowhood and retirement. All with free doctoring, dentistry and medicine – bath chairs too, if needed.

When, two days later, health secretary Aneurin Bevan opened Park Hospital in Manchester, it was the culmination of an ambitious plan to take care of the health care needs of the whole population and to make medical care free at the point of delivery to meet people’s needs. Dr John Marks, a newly qualified doctor working in Shoreditch, remembered:

The demand when the NHS started was unbelievable. Before the health service started, there was guaranteed treatment through National Health Insurance for low-paid workers, but their families were excluded. There was an enormous demand for surgery for previously untreated conditions.

In the years that followed VE day, Britain gradually rebuilt itself – the NHS, schools, houses and new towns. Finally, in 1954, the end of rationing provided the wherewithal for ordinary people to rebuild every-day family life and create the people’s peace.

Originally published in All About History 25

Subscribe to

All About History now for amazing savings!